Artillery: The Pulaski Light Artillery Battery’s Trial by Fire at Wilson’s Creek

ECW welcomes back Kristen Pawlak

Before dawn on the morning of August 10, 1861, the men of Capt. William E. Woodruff’s Pulaski Light Artillery Battery prepared their breakfast of green corn foraged from the farm fields in the Wilson’s Creek valley just fifteen miles southwest of Springfield, Missouri.[1] The 71 men of the Pulaski Light Artillery Battery nervously awaited action, like nearly every other soldier in Brig. Gen. Benjamin McCulloch’s Western Army. Just one month before, McCulloch’s Confederate army – made up of Arkansans and Texans – joined forces with Brig. Gen. Sterling Price’s Missouri State Guard to liberate Missouri from the Federal grasp of Brig. Gen. Nathaniel Lyon’s Army of the West. They were now on the brink of a major engagement along Wilson’s Creek and the Wire Road.

Rooted in the pre-war Arkansas State Militia since 1860, the Pulaski Battery was named for its home in Pulaski County, Arkansas. When it was first formed, the 50-man battery was designated the Totten Light Artillery after the prominent Totten family of Little Rock – specifically for Army Captain James Totten, who was then in command of the Little Rock Arsenal garrison, and his father and physician Dr. William Totten.[2]

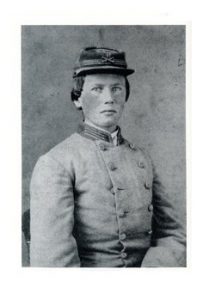

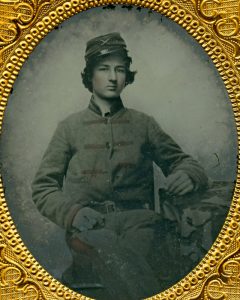

At that time, the state of Arkansas established its official militia system, in which the state drafted every male of military age to serve in local units.[3] Made up of merchants, artisans, mechanics, and laborers, the battery was under the command of Capt. Robert C. Newton, a young prominent Little Rock lawyer. One such soldier in the battery was 18-year-old college student Buck Parks, who joined the battery before graduating from St. John’s College. Even Omer Weaver, the son of the Arkansas Secretary of State, joined the militia as a lieutenant while also working as his father’s secretary. Though the soldiers had distinctly different backgrounds, the unit itself was united in their loyalty to their home state and sided with its secession, so much so that by February 1861, when Totten sided with the Union cause and surrendered the arsenal to Confederate forces, the Totten Artillery dropped their ties to the Unionist Totten family and renamed itself the Pulaski Light Artillery Battery. In their first major engagement at Wilson’s Creek, the battery would once again face its former namesake.

By the time the Pulaski Light Artillery arrived at the Confederate encampment at Maysville in Benton County, Arkansas in the early summer of 1861, the state – officially seceded from the Union – had mobilized its militia into the State Troops units with six of the regiments under the command of West Point graduate and Arkansan Brig. Gen. Nicholas Bartlett Pearce. The battery had joined five other State Troops units at Camp Walker, just south of the Missouri-Arkansas-Indian Territory border, which formed Pearce’s Western Brigade. Pearce committed his brigade to McCulloch’s Western Army – also included Sterling Price’s Missouri State Guard – in response to the growing Federal threat in Missouri.

In addition, the Pulaski Light Artillery had a new commander Capt. William Woodruff, Jr., who previously served as the unit’s first lieutenant until Newton accepted a Confederate officer’s commission at the start of the war. Just prior to joining Pearce’s brigade, the battery “received instructions by the hand of the secretary of the board to recruit the company to the maximum, select ordnance and stores from the [Little Rock] arsenal, prepare clothing.”[4] Though they did not receive all of Woodruff’s requests of side arms and one additional six-pound howitzer, the battery had 70 men armed with “Minnie rifles” and two six-pound and two twelve-pound smoothbore field guns.[5]

At Camp Walker, they continually drilled for hours each day, which, in the eyes of their commander, would accustom them “in the firing of blank cartridges singly, by the piece, by section, by half battery, and by battery. It proved to be a most wholesome performance.”[6] Captain James McIntosh even commended them on their performance in drill, saying “It was becoming really a fine light battery.”[7] On July 4, 1861, Pearce’s Western Brigade and the rest of McCulloch’s army moved into Missouri to meet the threat of Lyon’s Federal force that had just defeated Missouri Governor Claiborne Jackson’s small force at Carthage. Trained and armed, the Pulaski Light Artillery was ready for their trial by fire.

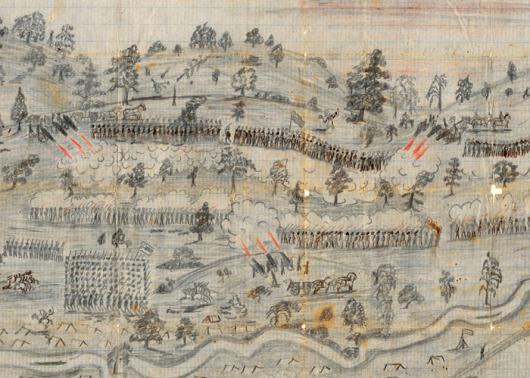

By early August 1861, the Western Army grew to over 10,000 men, double the size of Lyon’s Army of the West at 5,400 men; the two armies were within an arm’s reach of one another at that point near the crossroads town of Springfield, Missouri. Both commanders had overextended their supply lines and were vulnerable to a flank attack, but desperately wanted to attack the other and win a decisive victory. Along the Wire Road – the vital north-south road and telegraph line that connected St. Louis to Fort Smith – near the creek, Price’s and McCulloch’s men settled into camp the night of August 9. The men of the Pulaski Battery placed their four guns north of the Wire Road Ford along the creek in order to control the waterway and road. Both armies planned to attack the other, McCulloch to attack Lyon at Springfield and Lyon to attack McCulloch right where they were, the next day – August 10.

At dawn, Lyon’s troops had the Confederate encampment within their view from the north along the creek by Gibson’s Mill. McCulloch and Price’s men had just awoken or began making breakfast in preparation of the march to Springfield. Foraged from the surrounding Wilson’s Creek valley, the men quickly ate their green corn and drank hot coffee, unsuspecting of a pending attack. At 4:00am, Lyon ordered his men to advance against the southern flank of the Rebels but were quickly discovered by Confederate pickets. From across the creek near the Winn Farm, Captain Woodruff and his battery watched the Federals occupy the most prominent position in the Wilson’s Creek valley: Bloody Hill. For Woodruff, it was time to act.

Immediately, Woodruff “ordered officers and men to post” amongst the guns and caissons. To the northwest on Bloody Hill, “a rush of teams was observed, which rapidly developed into a light battery, that quickly unlimbered and commenced firing.”[8] Soon, a second battery deployed just next to the first. The enemy guns were those of Captain James Totten’s Battery F, 2nd U.S. Artillery, who quickly aimed his guns on the Pulaski boys. In his after-action report, Totten recalled that Woodruff’s guns were “within easy range of my guns … the gunners of my pieces were obliged to give direction to their pieces by the flash and smoke of the opposing artillery.”[9] The oncoming fire from Totten’s guns forced Woodruff to send his caissons towards the rear.

Soon, reinforcements from the 1st Iowa Infantry appeared on Bloody Hill and were immediately under artillery fire. One Iowa infantryman recalled, “a battery of artillery made a specialty of our ranks, opening out thunderously. We all laid down on the ground, and for some time the shells, round shot, and canister fell into our ranks.”[10] The effectiveness of the Pulaski Battery was clear when Captain Joseph Plummer’s battalion of U.S. Regulars attempted to take out their guns. Fortunately for the Arkansas artillerists, fellow Arkansans and Louisianans rushed to protect them and pushed back Plummer’s men in the infamous Ray Cornfield to the north of their position. The artillery duel between Woodruff and Totten lasted over one hour, as both armies clashed in the fields around them.

For the Western Army, the duel pinned Lyon’s men down into a position that protected advancing Missouri State Guard troops. The steep grade on Bloody Hill acted as protection against oncoming Federal artillery and small arms fire. Additionally, and most importantly, Woodruff’s Battery hindered the Federal push from Bloody Hill, and gave their fellow Confederates time to counterattack.[11]

Even though the battery’s firepower was effective against the enemy, the duel resulted in three casualties, including one that was irreplaceable for the Pulaski Light Artillery. Woodruff’s second-in-command, Lt. Omer Weaver, was struck in the chest and right arm by a solid shot early in the fight. He died soon after. Ultimately, after Brig. Gen. Franz Sigel’s flank attack failed, Lyon was killed in action as the first Federal General to die in the war, and resources were low, the Army of the West retreated from the field. The Confederates had won their first major victory west of the Mississippi River.

On August 11, 1861, the day after the Battle of Wilson’s Creek, Captain Woodruff left his battery’s position to inspect captured Federal troops in Sigel’s command. Scattered across the battlefield and in field hospitals were over 2,000 dead, wounded, or missing soldiers from both sides. On his way there, he passed by a company of Missouri State Guardsmen, who cheered for Capt. Woodruff: “There goes the little captain of the battery that saved us yesterday” Woodruff concluded on that hot, humid August day that “it was assured our boys had done well.”[12]

Kristen M. Pawlak is the Development Associate for Stewardship at the Civil War Trust. She also sits on the Board of Directors at the Missouri Civil War Museum, and actively volunteers with the Marine Corps Scholarship Foundation. She graduated from Gettysburg College in 2014 with a BA in History and Civil War Era Studies, and is currently pursuing her MA in Nonprofit Leadership and Management at Webster University. From St. Louis, Kristen has a fond interest in the Civil War in Missouri, Civil War medicine, and the war experiences of soldiers.

Notes and Sources:

[1] The official name of the creek was actually Wilson Creek, but veterans of the battle referred to it as “Wilson’s Creek.” For consistency and accuracy, we will use Wilson’s Creek as the name of the creek.

[2] David Sesser, The Little Rock Arsenal Crisis: On the Precipice of the American Civil War (Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2013), 80.

[3] “Militia Law of the State of Arkansas,” Arkansas Public Documents, 1854-1860 (Little Rock, AR: Johnson & Years, 1860), 6-7.

[4] William E. Woodruff, With the Light Guns in ’61-’65 (Little Rock, AR: Central Printing Company, 1903), 20-21.

[5] Ibid., 20; William E. Woodruff Letter to C. Peyton, February 14, 1861, Wilson’s Creek National Battlefield, Springfield, Missouri.

[6] Ibid., 29.

[7] Ibid., 30.

[8] Ibid., 30.

[9] James Totten, “Official Report,” August 10, 1861, in War of the Rebellion: Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1880), ser. 1, vol. 3, 73.

[10] Eugene Ware, The Lyon Campaign of Missouri (Topeka, KS: Crane & Company), 316-317.

[11] Dick Titterington, Sterling Price Returns: The Southern Counteroffensive to Retake Missouri in 1861 (Overland Park, KS: Trans-Mississippi Musings Press, 2014), 107.

[12] Woodruff, With the Light Guns in ’61 – ’65, 48.

Excellent article!

Thank you for the kind words, Terrance!

Very interesting article Kristen. Southerners had high hopes that James Totten would switch his allegiance to the south and were bitterly disappointed when it did not happen. While a number of regular artillery companies would serve in the Army of the Cumberland, Company F, 2nd US Artillery remained the only regular battery to serve in what would eventually become the Army of the Tennessee. There were a number of Woodruffs who served in the Union artillery too. Thanks for your work on this topic.

Thank you for reading the article and for commenting with some great insight, Jim! It would be interesting to see if there are any apparent genealogical connections between some of the other Woodruff artillerists.