The Good Death of Private John Ide: U.S. Sharpshooters at Yorktown, Part 3

Emerging Civil War welcomes back guest author Rob Wilson for Part 3–and the final “chapter”–of this mini-series. Click to read Part 1 and Part 2 about the U.S. Sharpshooters and their role at the Siege of Yorktown.

“Let me die the death of the righteous, and let my last end be like his.”

Numbers, 23:10, often quoted in Nineteenth Century funeral sermons

On March 26, 1862, Private John S. Ide mailed a lengthy description he’d written about the first days of the Army of the Potomac’s Peninsula Campaign to the Claremont [N.H.] National Eagle. His hometown newspaper printed the letter— in which he confidently predicted he would soon be marching “on to Richmond”— on April 3. Two days later, during the fierce daylong fight that launched the Siege of Yorktown, Ide was shot dead as his 1st Regiment, United States Sharpshooters (U.S.S.S.) engaged with Confederate infantry.

The story of Private John Ide at Yorktown did not end with his death on April 5. A week or so afterwards, U.S.S.S. Sgt. George A. Marden saw Ide’s letter about the campaign in a copy of the April 3 Eagle that had been mailed to the regiment’s camp. Realizing Ide’s family and friends probably knew little, if anything, about how he had died, Marden sat down to write a letter-to-the-editor about his fallen comrade for publication in the newspaper. “I thought a few items in relation to [Ide’s] death that might be of interest to his friends,” he wrote at the beginning of a long tribute to the soldier’s courage, his “righteous” service to the Union and his noble death. The Eagle published the sergeant’s letter on April 23.[i]

The above chain of events exemplifies the ways in which Civil War soldiers on both sides often responded to a comrade’s death. The final link in that chain was the letter attempting to comfort the family. Many of the nurses, chaplains and doctors who attended those dying of wounds or illnesses in hospitals wrote similar testimonies. Marden’s long letter to the Eagle was more than a message of condolence. It also described Ide’s death and burial, casting them in the light of the so-called “Good Death.” This long-established Christian construct provided guidelines for dying, burial and mourning which were widely followed in the North and the South.

The sharpshooter’s letter, however, conveyed few of the hallmarks of an antebellum Good Death. Like many of the authors of the condolence letters that historian Drew Gilpin Faust examines in her book, This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War, Marden had to adjust his words to the war’s brutal realities. The bloody conflict— which killed an estimated 750,000 Union and Confederate soldiers— was changing the ways Americans understood and viewed death. What the wartime letters said and did not say, Faust asserts, indicate major shifts in American traditions regarding dying and memorialization. The letter Marden composed— which is excerpted below and was not part of Faust’s study— highlights some of the changes.

Up until 1861, ninety-five percent of the nation’s deaths took place in the home and were attended by a dying person’s family. The assembled watched for the physical signs of a Good Death, indicators that many religious pamphlets and popular books, poems and songs interpreted as signs that a soul was heaven bound. Key clues included a calm demeanor, last words voicing an acceptance of dying, and a declaration of faith in the Almighty. A peaceful countenance at the moment of passing further signaled that eternal glory awaited. A period of mourning and a proper burial, with family participating, were the final elements of a Good Death. [ii]

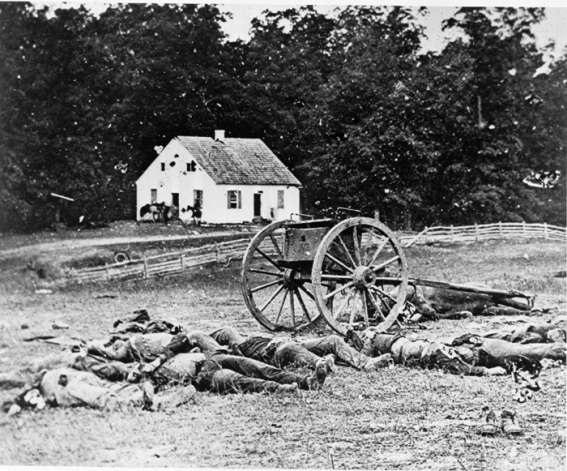

The war completely disrupted these home-based traditions. Soldiers perished hundreds of miles away from their homes. The dying might have a reflective moment in the care of a comrade, chaplain or nurse, or be in a place where last words, affirmation of faith and acceptance of death could be witnessed. Think of Stonewall Jackson’s last hours, when the general proclaimed he was grateful to die on a Sunday and later, with his wife nearby, uttered those often-quoted final words: “Let us cross over the river and rest under the shade of the trees.” But tens of thousands of soldiers— from privates to generals— died on chaotic battlefields or in crowded hospitals, far from their loved ones, many buried in mass or unmarked graves. As a federal chaplain quoted by Faust told his regiment, no one in their time “had ever lived and faced death” imposed with such “peculiar conditions and necessities.”[iii]

Private Ide’s instant demise in Southern Virginia— from a Confederate marksman’s Minié ball passing through his head— is just one example of the “peculiar conditions” that challenged the standards of the Good Death. Sgt. Marden’s message to the people of Claremont reveals how those challenges were addressed, through a type of letter Faust describes as a new genre of American writing.[iv]

Marden recently had been transferred from the 2nd U.S.S.S. Regiment to the command staff of the 1st and may not have known Ide. Writing his letter, he probably drew from what he had heard about the slain soldier from comrades. The church-going soldier likely could have conjured up antebellum imagery for a “proper” death. Yet, Marden apparently adhered to what Faust writes was the “honesty [and] scrupulousness in reporting” exhibited by many letter writers. There is little evidence of a traditional Good Death in the letter excerpt below.[v]

Ide was a brave and faithful soldier, and was always ready to do his duty. He greatly desired to get into active service, and when the sharpshooters were ordered to advance, and were placed in position to pick off the rebel gunners… his trusty rifle was often heard speaking destruction to the foe…

From 10 o’clock in the morning until 9 in the evening the fight raged unabated. Shell grape and shots from rifle pits were poured upon the sharpshooters, but they never flinched, and returned it with compound interest… Of the two [killed] Ide was one. He was shot through the head while aiming at the foe around the corner of a house. It was about four P.M. His body was got into the house and Lt. Col. Ripley, taking Ide’s [loaded] rifle, remarked that he “had a license to shoot that man” and brought him down at the first fire. The enemy then commenced to shell the house and it was impossible to bring away the body until after dark, when it was taken away and buried.[vi]

The kind of emphasis Marden places on Ide’s courage and other military virtues is common in wartime condolence letters. Faust writes that, as the war progressed, a soldier’s “duty to God and duty to country blurred, and dying bravely and manfully became an important part of dying well.” This kind of conduct and carrying on while under fire took the place of acts that had “traditionally prepared the way for the Good Death.” The sergeant does take care to describe the time, place and manner of death, and how the body was carried and buried by comrades. In a time when thousands of families were left with few or no details of how their soldier died, Marden was making Ide’s family and friends virtual witnesses to his passing and burial. Knowing that the men of Company E— Ide’s surrogate family in wartime— had attended to the fallen Sharpshooter provided some sense of a conventional Good Death.[vii]

Towards the end of his letter, Marden writes: “Thus fell Mr. Ide with his armor on, and in the thickest of the fight. He could not have died a nobler death, and his comrades will always remember how his example stimulated them, and while they have a country to be saved will pray that if they are to die, ‘their last end may be like his.’”

The phrase in quotes is the only religious reference in the letter. It is paraphrased from the Bible, Numbers, 23:10: Let me die the death of the righteous, and let my last end be like his. Rather than using a passage that testifies to Ide’s faith, his abiding belief in eternal salvation, or some other traditional indicator of a Good Death, Marden uses the Old Testament to present the image of a noble warrior dying righteously. Many Union and Confederate condolence letters and funeral sermons go even further, declaring fallen soldiers as Christian martyrs.[viii]

Faced with brutal realities of war, Faust writes, many kept to the traditional tenets of a Good Death as best they could. At the same time and on both sides of the battlefield, she continues, many began adhering to “a newly religious conception of the nation and a newly worldly understanding of faith.” Marden’s letter is one example of this redefinition. Another one of many Faust cited is a Confederate infantryman’s letter to the father of a slain comrade. No indicators of a Good Death are offered, just the consolation that the man’s son had “died in full discharge of his duty in the defense of his home & Country.” For many, a soldier’s ultimate sacrifice for his Cause— whether he wore blue or gray— had become an act of “holy dying.” The norms of the Good Death had changed and would never revert to their mid-century standards.[ix]

End of series.

Thanks to Arthur Ruitberg for sharing his digitized copies of the letters written by John Ide and George Marden that I cited above.

[i] George Marden, letter to the Claremont National Eagle (Claremont N.H., published April 24, 1862)

[ii] Drew Gilpin Faust, This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War (New York; Alfred A. Knoph, 2008), 14-22.

[iii] Ibid., 15; Dr. Hunter McGuire, “Death of Stonewall Jackson” (Southern Historical Society Papers Vol. 14, 1886. [For the full text of McGuire’s description of Jackson’s death, go to http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A2001.05.0271%3Achapter%3D9;

- Clay Trumbull, War Memories of An Army Chaplain (New York: C. Scribner’s Sons, 1898) 39, quoted in Faust, xiii. [Regarding Jackson’s words about crossing the river, his wife, Mary Anna, thought he likely was “reaching forward across the River of Death, to the golden streets of the Celestial City, and the trees whose leaves are for the healing of nations[.] It was to these that God was bringing him, through his last battle and victory; and under their shade he walks, with the blessed company of the redeemed.” If that was Stonewall’s meaning, his indeed was a Good Death. See Mary Anna Jackson, Life and Letters of “Stonewall” Jackson by His Wife (Harrisonburg, VA: Sprinkle Publications, 1995), 471, quoted in “Stonewall Jackson’s Last Words” Chris Mackowski, ECW, Dec. 21, 2016.]

[vi] Marden, letter to the Claremont National Eagle [Marden writes the fighting began at 10 a.m., while many other sources claim it started at 11. He may have been referring here to exchanges of fire between some Sharpshooters and Confederate cavalry that took place prior to the extended combat involving the 1st U.S.S.S. and Confederate infantry.]

[vii] Faust, 25.

[viii] Marden, letter to the Claremont National Eagle. [Marden’s letters indicate he was an abolitionist who had been brought up in and was an active member of the Congregational Church. He could have heard the Numbers verse from any number of sermons or eulogies by clergy. The abolitionist ministers of that era leaned heavily on the imagery of the fight to save the Union and end slavery as a just war and righteous cause sanctioned by God. To get a sense of the imagery of holy sacrifice and martyrdom on battlefield, glance through some of the Civil War funeral sermons for Massachusetts soldiers collected by the Harvard University Library archives: https://guides.library.harvard.edu/hds/civil-war/hds/civil-war-funerals.]

[ix] Faust, 25-26.