Around We Go: In the Monitor Turret

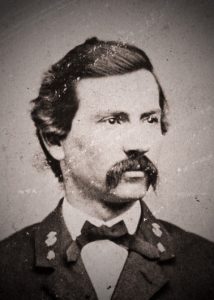

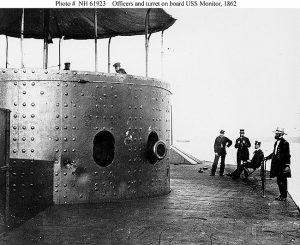

Lieutenant Samuel D. Greene, USN, had a problem. He was encased within a dim, claustrophobic, metal drum—20 feet in diameter—behind eight layers of bolted and riveted 1-inch-thick iron plates in charge of two immense 11-inch Dahlgren shell guns, each 13 feet long and weighing 9 tons.

With him were sixteen brawny sailors packed in eight to a gun, along with block and tackle to run the guns in and out, bore rammers, sponges, other gear, powder cartridges and 165-pound shells. Outside was a deadly enemy. The 22-year-old lieutenant couldn’t see the foe to point his guns. And the drum was rotating.

It was morning, Sunday, March 9, 1862. As executive officer and second in command of the revolutionary ironclad, USS Monitor, Greene supervised the weapons in the turret while his captain, Lieutenant John L. Worden, commanded the vessel from the little pilothouse some 50 feet forward of the guns. They had just sallied forth to meet the CSS Virginia (ex USS Merrimack) in the first contest between ironclad warships.

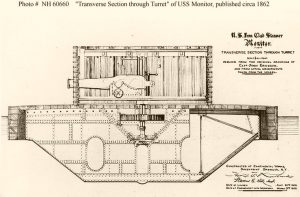

What natural light there was streamed down through ventilation holes in the iron plates over their heads. The curving walls or “bulkheads” were covered with additional thin iron sheets as shields to prevent hundreds of bolt heads and nuts binding the turret plates together from becoming shrapnel within when enemy rounds struck without. These internal surfaces were whitewashed to reflect light.

Monitor was equipped with a speaking tube—a pipe through which voice orders and status reports presumably could be exchanged between the captain in the pilothouse and Lieutenant Greene in the turret—but it apparently didn’t work well, perhaps due to incessant noise of engines and guns. The ship’s paymaster and captain’s clerk were assigned as messengers running between the two stations with verbal exchanges. “They performed their work with zeal and alacrity,” reported Greene, “but, both being landsmen, our technical communications sometimes miscarried.”[1]

Greene’s best and most dangerous view for aiming was through the few-inch gap between the muzzle of the gun and the top of the gun port when the gun was run out for firing. Green called down the hatch in the turret floor to the paymaster below, instructing him to go forward and ask Worden for permission to fire. The reply: “Tell Mr. Greene not to fire till I give the word, to be cool & deliberate, to take sure aim & not to waste a shot.”[2]

Finally, Worden closed Virginia to about a third of a mile, altered course, stopped the engine, and ordered, “Commence firing!” The gun port cover rumbled open; the big black muzzle protruded. Greene snatched a look over the barrel top, took aim, stepped back, and yanked the firelock string at 8:45 a.m. The entire structure throbbed and trembeled with a deafening concussion as the beheamouth gun lept inward.

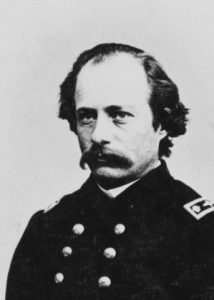

“Ironclad against ironclad,” recalled Monitor’s Chief Engineer Alban C. Stimers. “We maneuvered about the bay here and went at each other with mutual fierceness.”[3] They circled tightly, awkwardly, in what would appear to a modern observer as slow motion.

Guns bellowed as fast as they could be served. Choking white smoke shot with flame erupted from barrels. Rounds screamed, caromed, clanged, boomed, and splashed all around. Engines thumped and clanked; exhaust blowers roared. Black clouds billowed from stacks. Big propellers thrashed the water. Men enclosed in iron, many stripped to the waist with scraps of cloth around their ears, shouted, sweated, and struggled to manage their metal monsters.

The reverberation of Virginia’s shots against Monitor’s turret, noted Lieutenant Greene, “caused anything but a pleasant sensation.” But to the immense relief of the men therein, nothing penetrated, and the turret continued to revolve. “A look of confidence passed over the men’s faces and we believed the Merrimac would not repeat the work she had accomplished the day before” when the Rebel destroyed the wooden warships USS Cumberland and USS Congress.[4]

Acting Master L. N. Stodder was operating the crank handle on the turret bulkhead that started, stopped, and reversed the turret when he incautiously leaned against the bulkhead just as a Rebel shot whanged against the outside knocking him senseless and injuring his knee. Stodder went below. A few minutes later, Seaman Peter Trescott was sent down with a similar concussion.

Surgeon Daniel C. Logue administered small quantities of stimulants and applied cold presses; both men recovered full function and would be ready for duty by the following morning. They were the only injuries among the crew. Engineer Stimers also was flung down but not injured; he took over operating the turret.

With guns in for loading, the ports could be covered by massive, coffin-shaped iron shutters pierced with holes to allow the long-handled bore swabbing and ramming tools to pass through. The entire gun crew was required to haul on a block and tackle to hoist one of these heavy lids, but because they swung inward toward each other, only one could be opened at a time. In addition to the narrow opening over the top of the barrel, small sight holes to the left and right and directly behind the gun ports provided limited views.

White reference marks had been painted on the deck to indicate port and starboard, bow and stern, but these marks were obliterated early on. Both vessels were continuously turning, backing, and forwarding while the turret rotated independently. Greene passed a stream of “How does the Merrimac bear?” questions to the captain through the messengers. Worden replied: “On the starboard beam” or “On the port-quarter” as might be. The frequently disoriented lieutenant had difficulty not only knowing where the enemy was, but also how his own vessel was oriented relative to the guns.

Greene had two primary worries: first, to prevent enemy projectiles from entering the turret through open gun ports; a shell exploding inside would end the fight and there were no relief gun crews aboard. And second: “A careless or impatient hand, during the confusion arising from the whirligig motion of the tower,” might fire into the pilothouse directly in front. “For this and other reasons, I fired every gun while I remained in the turret.”[5] (Later Monitor-class warships would mount the pilothouse atop the turret.)

Two small auxiliary steam engines just below the deck drove this movement, which like all Monitor’s machinery, were undergoing their first combat trial. The brief test run in New York six days earlier established that the mechanism turned on its central shaft at two and a half revolutions per minute under 25 pounds of steam.

Engineer Stimers, “an active, muscular man” according to Greene, found the turret almost unmanageable as he manipulated the lever to admit or throttle steam to the drive engines—slow to start and once moving, slow to stop.

Unlike traditional broadside guns like those in Virginia, it was nearly impossible to fix the enemy in line of fire long enough to aim and shoot, a truly unprecedented dilemma. So, Greene settled on a pattern: rotate the turret away from Virginia; stop the turret and load, leaving the gun ports open to save time and effort; when ready, start revolving again and fire “on the fly” as the target swept past the muzzles.

“We could only see [Monitor‘s] guns when they were discharged,” reported Lieutenant Catesby ap R. Jones, commanding Virginia. “We wondered how proper aim could be taken in the very time the guns were in sight. The Virginia, however, was a large target and generally so near that the Monitor‘s shot did not often miss. It did not appear to us that our shell had any effect upon the Monitor.”[6]

After pounding each other for three hours with no noticeable damage to either, the contestants mutually withdrew. The battle was over, at least for the day.

Lieutenant Greene: “My men and myself were perfectly black with smoke and powder. All my underclothes were perfectly black …. I had been up so long, and been under such a state of excitement, that my nervous system was completely run down…. My nerves and muscles twitched as though electric shocks were continually passing through them… I lay down and tried to sleep—I might as well have tried to fly.”[7]

Among the other technological innovations of this contest, the armored, rotating turret passed its first test in battle, but it would need improvement.

(Excerpted from a book in progress: With Mutual Fierceness: The Battles of Hampton Roads.)

[1] Dana Greene, “In the ‘Monitor’ Turret,” in Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, Being for The Most Part Contributions by Union and Confederate Officers, 4 vols. (New York, 1884-1888), vol. 1, 724.

[2] Robert W. Daly, ed., The Letters of Acting Paymaster William Frederick Keeler, U.S. Navy to His Wife, Anna (Annapolis, MD), 34.

[3] Stimers to Ericsson, March 9, 1862, in Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion (Washington, D.C., 1894-1922), Series 1, vol. 7, 26.

[4] Greene, “In the ‘Monitor’ Turret,” 723.

[5] Ibid., 725-726.

[6] Catesby ap Roger Jones, “Services of the Virginia.” Southern Historical Society Papers 11 (January 1883), 71.

[7] Greene, “In the ‘Monitor’ Turret,” 727.

I love that first picture of the two ships. Any idea where I could find a copy? Thanks for another interesting story.

Just . . . Wow!

I’ve never read this descriptive telling of the Battle of Ironclads before. Very good. The photo of the recovered turret illustrates just how crowded it must have been for sixteen men and those huge guns!

Impressive but based on the drawings for manufacture, I cannot tell how the turret rotation mechanism would possibly work. Need more visual data

great article with information I had never seen documented before.