Lukewarm Patriots: Examining the Pension Files of Late-War Recruits in One Union Regiment

Emerging Civil War welcomes guest author Nathan Marzoli

On a cold December morning in 1863, John Prescott of the 12th New Hampshire was awakened by “a strange noise” outside of his tent on the sandy shores of Point Lookout, Maryland. Pulling on his clothes, the veteran of Chancellorsville and Gettysburg threw open his tent flap and found a group of eighty-three new recruits standing in formation for roll call to be turned into his depleted regiment. Before the day was over, Prescott had surmised that these men hailed from many different countries – in addition to some Americans, he claimed there were men from France, Germany, Sweden, Scotland, Portugal, Ireland, Russia, Denmark, England, and Canada – and confessed in his diary that he was worried whether these men would make good soldiers.[1]

Prescott was certainly not alone in his negative assessment of the recruits who began pouring into veteran Union regiments starting in late 1863. “They are the off-scourings [sic] of society,” another soldier in the 12th New Hampshire complained to the Laconia Democrat, “men who came here, not for the good of their country, but for the bounty they received, intending to desert at the first opportunity.”[2] These men had been brought in under the auspices of the 1863 Enrollment Act, which established the first mass conscription in the United States. The reality of the law, however, was that it was never designed to force men into service, but rather to stimulate volunteering. A draft would only be held in states that did not meet their enlistment quotas, so states enticed men with the promise of high bounties to avoid the stigma that accompanied conscription. Even when a draft was held, conscripts could claim exemption through medical reasons, “commute” their service by paying $300, or hire another man – a substitute – to serve in their place. The result was that very few drafted men were actually held to service. This convoluted enlistment process, coupled with waning enthusiasm for the war and the depletion of willing manpower, unfortunately did attract many men who had no real vested interest in the fight and often deserted at the first opportunity.

Although this reputation – soldiers of questionable character who merely enlisted for money – has followed these recruits throughout history, the majority did not desert and fought alongside the veteran soldiers in the final campaigns of the war.[3] We have primarily been told the Union soldiers’ story through the eyes of the original volunteers of 1861 and 1862. But don’t the stories of the late-war recruits, substitutes, and draftees deserve to be included in the overall narrative? The problem for studying their experiences has generally been the lack of source material; the early-war volunteers left us with more letters and diaries, and also wrote most of the memoirs and regimental histories. But a look into the pension files of the recruits of just one infantry regiment from the Army of the James – the 12th New Hampshire – yields some clues about the experiences of these latecomers to the Union army.

Some pension files provide insight into how these men ended up in the service. Maine sailor Edward Bramhall fell in with a group of six or seven others at a boarding house in Boston who were on their way to Portsmouth, New Hampshire, to enlist and collect the bounty. Bramhall, who enlisted under a false name because he claimed he wanted to avoid alerting the captain of his ship, could not even remember if he joined as a substitute or not. “I only know I put my name down as examined and put on…blue clothing,” Bramhall told the man investigating his pension claim, “then I was handed $200 and sent to Concord, N.H.” where he enlisted in Company H of the 12th.[4]

Other veterans told more nefarious stories that highlights the questionable enlistment practices that became common during the latter stages of the war. Daniel Cummings, a sailor from Ireland, told pension agents he found shipping in New York City “dull” in late 1863. When someone at his boarding house told him that “big bounties were being paid” to men who enlisted up in New Hampshire, Cummings jumped at the opportunity. He claimed, however, that this same man from the boarding house took advantage of him. The man told Cummings to take the alias William Wilson, got him “pretty well ‘soused’” on the way to Concord, and supposedly kept for himself all but $200 of the $700 bounty.[5]

Max Kern, a recent German immigrant, also claimed that he was partially tricked into enlisting in the Union army. A stranger in a foreign country, Kern befriended two men who spoke his language; a week after they met, the two men tried to convince Kern to enlist with them in the army so they could each get a $200 bounty. Besides, they told Kern, “the war will be over in 3 or 4 months and maybe we may not go to the front at all.” The German was initially hesitant. “I told them that my friends and relations do not want me to go into the Army and if I enlisted it would be in the newspapers.” No problem, the men said, “we[’ll] call you by the name of ‘John Miller’”. At the recruiting office, the two men did all the talking – in English – so Kern hardly understood a word. “I enlisted in the name of John Miller,” he recalled,” but my acquaintances did not [enlist]…and I have not seen or heard from them since.”[6]

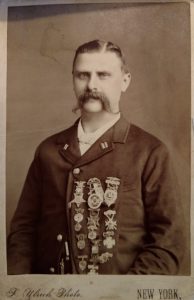

These pension files even hint that their reputation as inferior soldiers continued into the postwar period. James Collins had the index and middle fingers of his right hand shot off while on picket duty in Virginia in 1864. Seemingly cognizant of the reputation of recruits, Collins went into painstaking detail (even providing photographic evidence) in his pension claim to prove that he was actually shot by the enemy – and not by his own rifle.[7] Numerous other pension claimants also struggled to secure post-war affidavits of their service from officers or other former members of the 12th because they seemingly never integrated into the unit. Frank Seymour, for example, a French-Canadian who served in Company C, had trouble finding someone who could vouch for his wounding at Cold Harbor. “My Regiment and Company was about all from New Hampshire and [Quebec] was my home before the war and has been since,” Seymour explained. “I don’t know of any of the company that I could find that know anything about the matter.”[8]

So what might these few brief stories tell us? The story of the Union soldier – carved out by the likes of Wiley, McPherson, Mitchell, and Robertson – may not yet be complete. In the final year of the war, the remaining volunteers of 1861 in the East were joined by thousands of Union recruits, substitutes, and draftees in their final fight against the Army of Northern Virginia. The stories of these men, no matter their motivations or the circumstances surrounding their enlistment, deserve to be told. The pension files of even just one Union regiment seem to indicate that this might be possible.

Of course, pension files have their limitations. Everything in a claim was written with the motive of getting a veteran his pension, so stories might have been deliberately altered or stretched to achieve that goal. Additionally, most of the depositions for claims were written several decades after the war, so some men may just have simply forgotten exactly what happened during their service in the Union army. There is also the major issue of research access. One can only pull a maximum of twenty-four pension files on any given day at the National Archives, so it would take literal years to conduct even a survey of the hundreds of thousands of pension files of men that joined the Union army under the auspices of the Enrollment Act in the final two years of the war. Nevertheless, this look at just one regiment shows us that there might be more ink to spill about the experiences of the Civil War soldier.

Nathan Marzoli is a historian at the U.S. Army Center of Military History in Washington, D.C., where he specializes in unit history and leads staff rides to Civil War battlefields. He has a BA and MA in History from the University of New Hampshire. His publications include “‘Their Loss Was Necessarily Severe:’ The 12th New Hampshire at Chancellorsville,” and “‘We Are Seeing Something of Real War Now:’ The 3d, 4th, and 7th New Hampshire at Morris Island, July-September 1863” (winner of the 2017 Army Historical Foundation’s Distinguished Writing Award). He is currently working on a study of substitutes in the Union army.

Sources:

[1] John Prescott diary, December 18, 1863, New Hampshire Historical Society (NHHS).

[2] James McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988), 600; “Letter from the 12th Regiment,” The Laconia Democrat, December 18, 1863.

[3] The Army of the Potomac and James, more so than the Western Armies, were filled with the majority of the recruits. The reason was primarily because more of the western soldiers reenlisted when their terms were up. According to Joseph Glatthaar, nearly one out of two men in Sherman’s army during the March to the Sea and through the Carolinas had reenlisted for another three-year term. The figure for all Union armies was only one in every fifteen.

[4] Edward Bramhall pension file, National Archives and Records Administration (NARA).

[5] Daniel Cummings pension file, NARA.

[6] Max Kern (John Miller) pension file, NARA.

[7] James Collins pension file, NARA.

[8] Frank Seymour Pension File, NARA.

An under-appreciated aspect of the Civil War… the thousands upon thousands of men (and women) who carried scars of their experience for the next 20, 30, 50 years (regardless if they were “Three-years’ men,” or “Ninety-day volunteers,” or volunteer nurses.) The War Pensions and Bounty Land schemes were commendable programs designed to recognize the sacrifice of veterans. Unfortunately, the “administrators” of those programs were “the weak link,” forcing veterans who had spent months confined as POW; or with mental or internal injuries; or with weakened health (due to an illness or condition contracted during service) to jump through hoops to “prove” they were deserving of the crumbs on offer is nothing short of monstrous. Worse, wives and children of affected veterans were often the ultimate sufferers, when valid claims — unable to be verified — were denied.