British Rebels: The International Civil War

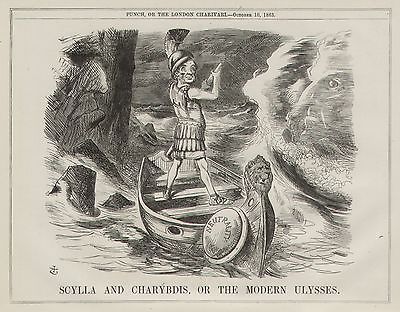

The Confederacy campaigned vigorously for international recognition and support while the United States risked war with Great Britain to prevent that eventuality.

Civil War aficionados might be familiar with “King Cotton” and perhaps the Trent Affair, but few recognize how critical the issue of neutrality—or lack thereof—was.

The British were horrified, confounded, and conflicted by the American Civil War, which generated near disastrous internal consequences. They were not required by international law to stand idly by while their politics, economy, and domestic stability were disrupted by someone else’s quarrel. Ancient and thorny debates resurfaced over issues of neutrality, blockade, trade, contraband, finance, and defense of Canada.

In summer 1862, parliament and the Queen’s ministers seriously debated intervention, armistice, and arbitration, perhaps under the guns of the Royal Navy. Had they done so, the Confederacy might well have gained independence. Henry Adams, son and secretary to Charles Francis Adams, United States Minister in London: “As for this country [Great Britain], the simple fact is that it is unanimously against us and becomes more firmly set every day.”[1] Powerful constituencies were sympathetic to the Southern cause. Why?

Confederate sympathizers were primarily aristocrats, politicians, and leading businessmen called “the educated million.” Working classes, even in textile manufacturing affected by cotton shortages, supported the Union. They were encouraged by radical politicians and activists opposing the government. However, this opposition did not coalesce into a significant political force until later in the century when additional political reforms expanded the franchise to the laborer.

During the war, the minority educated million were the voters and they constituted public opinion. Many became convinced early and maintained the thinking until very late that the North could not prevail; the United States would split. Partially this was wishful thinking and partially the prism of misunderstanding, misinformation, and bias through which they observed. Multiple layers of historical, social, economic, and geopolitical factors, abetted by ignorance of true conditions in America, underlay the response in favor of the South. Three major questions—slavery, union, and independence—drove the confusion.

There was no lack of antipathy for the institution of slavery. Great Britain outlawed the slave trade in 1807 and slavery itself a quarter century later. British Evangelicals led the crusade, achieving the first social and civil consensus in history on the immorality of involuntary servitude; they inspired American abolitionists. However, most of the elite were receptive to Confederate propaganda that slavery would be ended in their own good time, not as forced upon them by northern tyrants.

Emancipation of British slaves in the West Indian sugar plantations had been necessary and right, but an economic disaster and a bitter experience. It was easy to believe that Southern victory would benefit child-like Africans by promoting gradual and enlightened emancipation from kindly and paternal care. In addition, the British quickly concluded that the war was not even about slavery—President Lincoln and Secretary of State Seward repeatedly said as much—and Yankees had been very much complicit in the illegal slave trade.

The mystical concept of union advanced so eloquently by Lincoln had little resonance for Britons with no experience of a written constitution or a federal system. Their constitution consisted of venerated practices and institutions inherited from the mists of time, not a single document or an overarching principle. They were unified by history and by ethnicity, religion, and geography. No society had ever been conceived solely on a principle of individual freedom as claimed by the Americans. They did not appear to be following the ideal in any case. The strange system devised in 1787, based on a complex separation of powers, was unworkable.

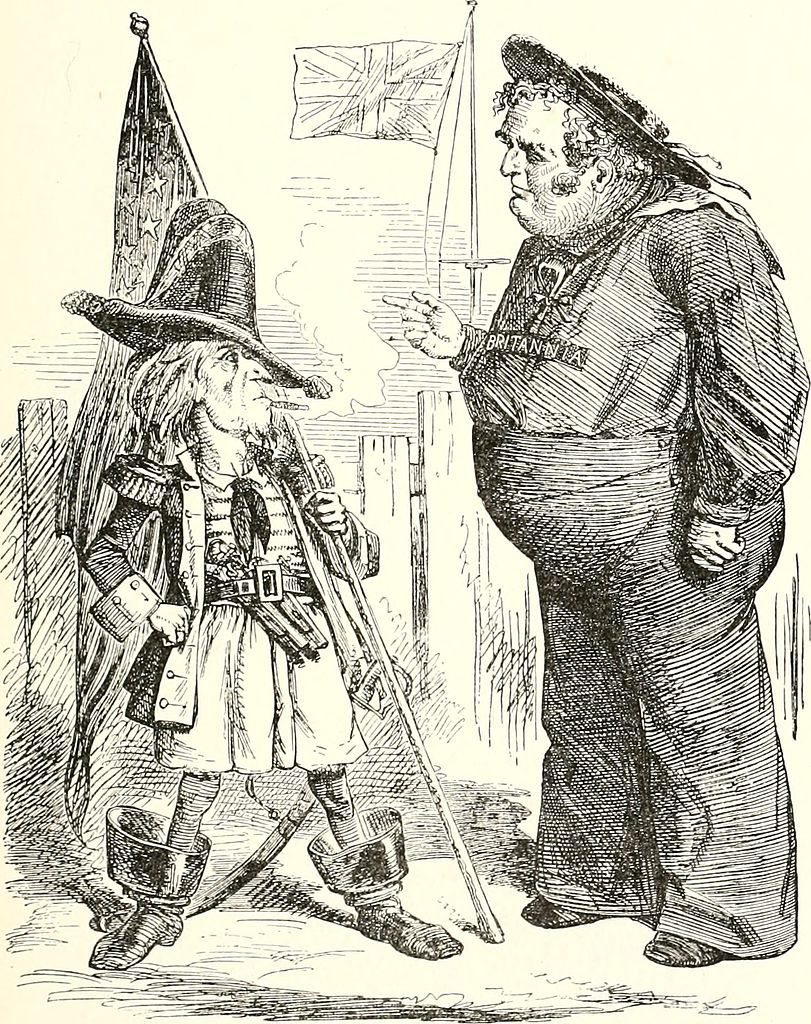

British opinion also exhibited a growing ambivalence toward their empire flourishing in Africa and Asia. In conflict and commerce, they were undisputed rulers of the waves and of large slices of the globe. While intensely proud of these accomplishments, many concluded that the Declaration of Independence might have been right in some sense. The natural course of civilizing influence in overseas enterprise motivated colonies toward independence in a modern commercial and industrial world.

The United States was a child of Great Britain and had been an immense success, in which, despite disagreements, they could take great satisfaction. It behooved them to accept and support this pattern of self determination, not fight it. The British sympathized with Greek and Italian freedom and supported independence for Spanish American colonies and Belgium. Their experiences in North America and the West Indies demonstrated the burdens as well as the benefits of colonial rule.

So, if slavery was not the issue, union did not make sense, and independence was a natural consequence of colonial maturity, this war must be about conquering a people who wished to be left alone. The Confederacy’s legal claim to secession seemed solid on the principles of 1776. The United States once fought for independence and now was grasping at empire, even threatening British Canada. Eighty years before, rightful rulers had been despised and rebels honored; now rebels were traitors.

Resentment lingered over the Revolution along with the petty fuss initiated in 1812 while the British were engaged in an existential struggle against Napoleon. As insistently argued by Southerners, why shouldn’t the Confederacy do to the United States what the colonies had done to Great Britain? And how could the North conquer the South where Cornwallis had failed? The land was huge, as big as Russia in Europe, inhabited by their own feisty Anglo-Saxon blood. The Times of London advised the North to, “accept the situation as we did 80 years ago upon their own soil.”

Pro-southern sentiment extended to domestic politics and culture. One historian wrote that the South the Englishmen saw, “is not necessarily the South as it saw itself, although it is not so far from that, nor is it the South as American historians variously see it today. The embattled South that England saw was aristocratic and thoroughly English—a land of chivalrous gentlemen—and it was made up principally of Virginia and Carolina.”[2] Southern leaders had founded the nation and dominated the first half century of its existence. Elite Britons did not see, or did not choose to see, the tragedy of deep South cotton, rice, and tobacco fields.

On the other hand, upper classes remained in fear of unrestrained democracy with extension of the franchise, causes they associated with northern politics in America and rising radical politics at home. The educated million drew sharp distinction between freedom and equality; they loved the former and hated the latter. Universal (male citizen) suffrage had never survived for long, not in Athens or in Rome. The French Revolution demonstrated the evils of mob rule precipitating a descent into chaos leading to the greatest tyranny of modern times and a mortal threat that many of their fathers and grandfathers had fought and died to avert.

The South was fighting with fortitude and resolution for freedom under men cut from the same cloth as Washington and Jefferson—Jefferson Davis, Robert E. Lee, JEB Stuart, Stonewall Jackson, and Raphael Semmes—paragons of military genius, courage, patriotic valor, and sacrifice. Lee ranked with Wellington among the great generals of English blood. A cause fought for so valiantly by such men must be a just one.

This in stark contrast to a bumbling Illinois frontiersman, a gang of loud-mouthed politicians, and a covey of incompetent generals.

One friend of the Union noted that the North had not displayed the qualities likely to be appreciated in Great Britain—external dignity of attitude, a stern and haughty countenance, a quiet air, absence of ostentation and brag.

The government of Jefferson Davis, “spoke little and hit hard, came forth calm in adversity and modest in success, kept its eye fixed on its purpose, and strode towards it with resolute step.”[3]

Another Union sympathizer feared that England was being carried away by, “the superior pluck, the unanimity, the energy, the military talent, and the modest but earnest proclamations of the South—[whilst being repelled] by the mismanagement, the divided counsels, the boastful language, the political corruption of the North.”[4] The English were more inclined to advocate a bad cause defended in proper form than a good cause badly defended.

The death of Stonewall Jackson at Chancellorsville caused an extraordinary outpouring of grief, probably more so than for any foreign general in British history. Victories of the commerce raider CSS Alabama were greeted with cheers in the House of Commons. Lord Acton wrote to General Lee after the war complementing him for fighting the battles of English freedom and civilization and concluded: “I morn for the stake which was lost at Richmond more deeply than I rejoice over that which was saved at Waterloo.”[5]

These judgments coalesced upon a foundation of poor information. Before the war, articles and stories about America in British publications were rare and typically snide and condescending when not distorted or just wrong. They paid little attention to industrial development, transportation systems, population trends, and armament capacity, concentrating instead on habits, manners, dress, and food.

The dramatic growth of population, industry, and railroads in northern states during the 1850s and thus the dynamism of the machine age economy that would finance the war had not been apparent across the Atlantic. Most bulletins on the war were short, inaccurate, and even false, reaching Britain weeks after the fact by packet from New York or Halifax, and for the first two years of the war almost uniformly describing Confederate victories.

The London Dispatch summarized prejudices of the English ruling classes: “The real motives of the civil war are the continuance of the power of the North to tax the industry of the South and the consolidation of a huge confederation to sweep every other power from the American continent, to enter into the politics of Europe with a Republican propaganda, and to bully the world.”[6] Elements of this argument are familiar today.

But the Battle of Antietam in September 1862 followed by the Emancipation Proclamation effectively countered those clamoring for intervention. The Union actually might prevail and slavery really was an issue. The Queen’s ministers and leaders in Parliament determined that discretion–and neutrality–remained the best policy; they could manage the internal disruption. This outcome was one of President Lincoln’s primary motivations for issuing the proclamation. There was no serious talk of intervention after January 1863.

Primary References:

Sheldon Vanauken, The Glittering Illusion: English Sympathy for the Southern Confederacy (Washington, D.C., 1989).

Dean B. Mahin, One War at a Time: The International Dimensions of the American Civil War (Washington, D.C., 1999), Chapter 3, “A Powerlessness to Comprehend, British Reactions to the American Civil War.

[1] Vanauken, The Glittering Illusion, 2.

[2] Ibid, 4.

[3] Ibid, 62.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid, 103.

[6] Mahin, One War at a Time, 30.

The British attitudes towards slavery in the US are interesting to say the least, given their complicity in bringing that peculiar institution to America’s shores.

Essentially every society in history on every continent had been complicit in slavery. What is truly remarkable is that the British were the first to end the practice just because it is wrong despite extreme political and economic pressure to continue it. They did this based on fundamental Judaeo-Christian principles of human worth, dignity, and freedom that became the foundations of this country, and led to the extinction of slavery here only eighty years later after millennia of near universal acceptance and a bloody war.

Well, you put it as them (the British) eliminating it “just because it was wrong”. They were quite comfortable with it when it served them and their interests. They had no problems with the slave harvested cotton from America that fed their mills. Various factors contributed to their determining that it was ‘wrong’ to continue it, as your article touches on. Slave revolts in places like the Caribbean had an impact, as did changing economic circumstances. And yes, there were those who argued against it on moral grounds. Sounds a lot like what went on in America up to its elimination.

‘

Since the dawn of man there has been slavery and it still exist today.

But we’re talking about slavery and Great Britain, not the rest of the world. And specifically that subject within the context of the American Civil War.

What a terrific read. I have always wondered just what it was that made the Confederacy so appealing to Britain & France. I knew Albert, Victoria’s husband, was strongly anti-slavery, so I guessed the Crown was not pro-southern. I love this topic–especially the comment “This in stark contrast to a bumbling Illinois frontiersman, a gang of loud-mouthed politicians, and a covey of incompetent generals,” which is wonderfully true, although they are my bumblers, gangs and coveys. Thanks.

You’re welcome, Meg. Thanks for the comment!

“Stay Calm & Take Richmond!”

For those with an interest IRT “how Britain viewed the American Civil War,” the following is an excellent read: “My Diary, North and South” (compiled in 1861 by William Howard Russell, journalist for The Times of London) and published 1863 at Boston by TOHP Burnham, and available online http://archive.org/stream/mydiarynorth00russrich#page/n9 .

Russell started his visit in New York, before culmination of the Excitement at Fort Sumter, and on page 24 reveals, “The papers are full of Sumter and Pickens…” During his stay in the North, Russell met William Seward, Abraham Lincoln and members of Lincoln’s Cabinet, and recorded his impressions (as well as providing descriptions of New York, Philadelphia and Washington) through to page 43. Concerns of British interest: the Federal blockade of Southern ports, and the Morrill Tariff.

After Fort Sumter surrendered, William Russell went south, and met Louis Wigfall, Jefferson Davis and members of Davis’s Cabinet (pages 172 – 176). He also visited the battered Fort Sumter, slave pens, and a plantation; and recorded his impression of the operation of slavery in the South, as well as recording the receipt of news of the attack on the 6th Massachusetts in Baltimore (pages 99 – 171).

There are an abundance of gems in this work, which Civil War enthusiasts will appreciate.

Thanks Dwight. I enjoyed reading your well-researched examination of what they thought on the other side of “The Pond” about the Civil War, and on what they based their opinions. I knew a little about the debate in England about intervention and how their recognition of the Confederacy would have jeopardized Lincoln’s agenda and Union victory, but I knew little about the underlying story. I learned a lot.