Prisoner of War or Constructive Deserter?

It pays to read the (often lengthy) footnotes when researching first-person accounts in the venerable Battles and Leaders of the Civil War. Seemingly minor vignettes can speak to big issues. An article by Colonel Rush C. Hawkins describing his service in the Sounds of North Carolina with the 1862 Burnside Expedition provides an example.

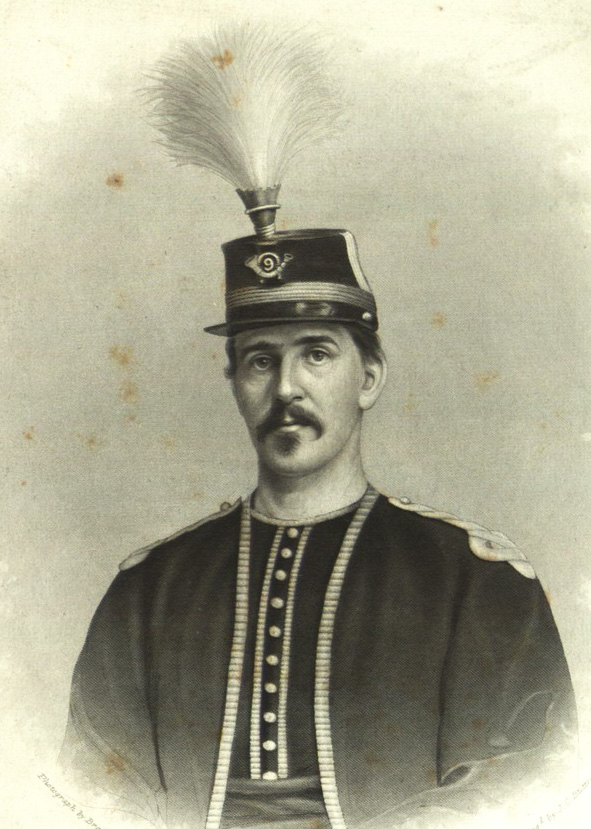

In an otherwise unremarkable action in June of that year, Hawkins’s navy counterpart and friend, Lieutenant Commander Charles W. Flusser, steamed his gunboats into and occupied the town of Plymouth near the mouth of the Roanoke River. Shortly thereafter, Hawkins arrived with Company F of his 9th New York Zouaves to assume guard and observation duty.

“It did not take a long time for us to ascertain that there were among the non-slaveholding population many who professed sentiments not hostile to the Union, and that they had expressed a determination never to serve in the ranks of the rebel army,” recalled Hawkins. “Lieutenant Commander Flusser constantly urged upon me the importance of enlisting these men in the cause of the United States. Nearly all of the poorer class of inhabitants were still devoted to the old government; and many had successfully resisted rebel conscription, and had never given their allegiance to the rebel government.”

Very few of these men were slave owners and presumably had little interest in aiding the rebellion. They worked their fields in groups with arms near at hand during the day, and at night retreated to the swamps for shelter against conscripting parties of rebel soldiers.

Constantly on the alert, they avoided all efforts to force them into the Confederate army. Commander Flusser urged Colonel Hawkins “in the strongest manner” not only to occupy the town, but to organize local men into a regiment of Union soldiers.

Hawkins conferred with General Burnside who placed the affair entirely in the colonel’s hands. Accordingly, he and Commander Rowan—officer in charge of local naval forces—met some two hundred and fifty Union men, “and a free interchange of views in relation to the affairs of the country took place.” The matter of great concern with them was, “What will become of us in case we are captured by the rebels?”

The colonel and the commander assured them “that the Government of the United States would protect them and their families to the last extreme, and that any outrage perpetrated upon them or upon their families would be severely punished.” An enlistment-roll was made out; about one hundred men signed their names at once. “Too much cannot be said of the devotion of these men under peculiar dangers—of these men of the 1st North Carolina,” concluded Hawkins.

In July, General Burnside’s command was ordered to join the Army of the Potomac on the Peninsula. Thus ended Hawkins’s narrative with the following author’s footnote: On February 1, 1864, a large Confederate force under command of Major General G. E. Pickett advanced upon New Berne, N. C, destroyed the United States gunboat Underwriter, burned a couple of bridges, captured some prisoners, and withdrew to Kinston. Among the prisoners were several who had previously enlisted in United States service. A court-martial composed of Virginians was convened. Twenty-two of these loyal North Carolinians were convicted of and executed for “(constructive) desertion.”

On June 1st, 1865, Pickett applied to President Johnson for a pardon. Secretary of War Stanton and Judge Advocate General Holt suggest trying him for executing the prisoners at New Bern and held up his application. Hearings included testimony that at least some of the executed men had volunteered for service in local militias during Union occupation. Their subsequent and unwilling conscription in the Confederate army had violated those enlistment agreements. They should have been treated as prisoners of war, not deserters. Fearing prosecution, Pickett fled with his wife and son to Canada.

March 12th, 1866, Pickett wrote to Lieutenant General Grant, once more stating his grievances and setting forth his claim for a pardon. Upon the back of that letter General Grant made this singular endorsement: “During the rebellion belligerent rights were acknowledged to the enemies of our country, and it is clear to me that the parole given by the armies laying down their arms protects them against punishments for acts lawful for any other belligerents. In this case I know it is claimed that the men tried and convicted for the crime of desertion were Union men from North Carolina, who had found refuge within our lines and in our service.

“The punishment was a harsh one, but it was in time of war, and when the enemy no doubt felt it necessary to retain by some power the services of every man within their reach. General Pickett I know personally to be an honorable man, but in this case his judgment prompted him to do what cannot well be sustained, though I do not see how good, either to friends of the deceased or by fixing an example for the future, can be secured by his trial now. It would only open up the question whether or not the Government did not disregard its contract entered into to secure the surrender of an armed enemy.”

The matter was referred to the president. Concluded Hawkins: “The indorsement of General Grant was all-powerful, and nothing was done.”

Hearing of Grant’s endorsement, Pickett returned to the United States with his family in 1866 to work as an insurance agent and farmer in Norfolk, Virginia. On June 23, 1874, House Resolution 3086, an “act to remove the political disabilities of George E. Pickett of Virginia”, passed the U.S. Congress. Pickett was granted a full pardon about a year before his death.

Rush Hawkins mustered out with his regiment in 1863, served in the New York Militia, and in 1866, was granted the grade of brevet brigadier general of volunteers in consideration of prior service. He became a Republican New York Assemblyman and noted rare book collector. Hawkins was struck by a car while crossing the street in front of his 5th Avenue home and died of injuries, October 25, 1920, age 89.

Charles Flusser was killed on April 19, 1864, in an engagement between his gunboat Miami and the Confederate ironclad CSS Albemarle. Flusser personally fired a shell with a 10-second fuse, which bounced off Albemarle’s armor, landed back on Miami’s deck, and exploded at his feet.

Primary Reference: Rush C. Hawkins, “Early Coast Operations In North Carolina” in Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, Being for The Most Part Contributions by Union and Confederate Officers. Based Upon “The Century War Series.” Edited by Robert Underwood Johnson and Clarence Clough Buel, of the Editorial Staff of “The Century Magazine”, 4 vols. (New York, 1884-1888), Vol 1, 658-659.

How ugly war becomes! Another reminder of how much we should work vigilantly to avoid war!

AMEN.

It is my belief that all wars stem from misunderstanding… A peaceful nation misunderstanding the intentions of a bellicose State (1941 Pearl Harbor.) An aggressor misunderstanding the likely response of his victim (April 1861 Fort Sumter.)

Stop the misunderstandings, and you stop the wars.