Disaster in the Defenses of Washington: The June 9, 1863 Explosion at Fort Lyon

Emerging Civil War welcomes back guest author Nathan Marzoli

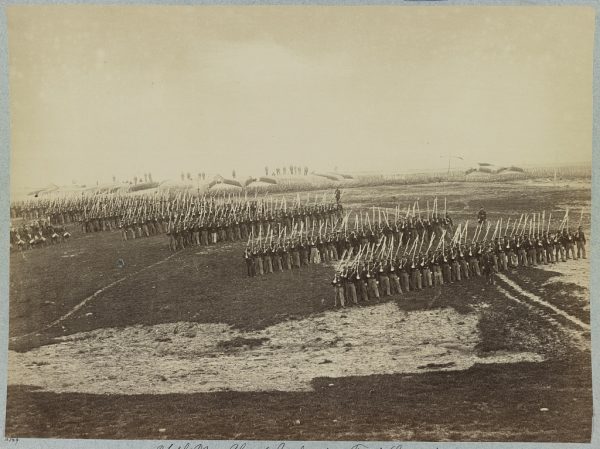

Lewis Bissell, a soldier in the 2nd Connecticut Heavy Artillery, had spent the better part of a year stationed in the numerous forts and batteries that ringed the nation’s capital. He had grown accustomed to the monotonous routine there, and probably expected June 9 to be another hot, sticky day of fatigue duty in which the men “sweat their shirts through and [got] as wet as though dipped in a mud puddle.” But as he left his barracks near Fort Lyon, Virginia, that afternoon to go work on the construction of a redoubt, Bissell’s world came crashing down around him.

The Connecticut soldier suddenly heard a popping of shells that sounded like firecrackers, “only a great deal louder.” Before he could realize what was happening, there was a stunning crash. Shells whizzed through the air all around him. Bissell immediately hit the ground and flattened himself to the dirt, praying that the stumps and logs around him would provide protection from the flying shells.

Anne Frobel, a local Alexandria resident, was at her home when she heard the “most violent thundering explosion, followed by another, in quick succession.” As “the earth shook and trembled,” a terrified Frobel looked over to nearby Fort Lyon, “which at that moment went up with a tremendous shock.” The blast reminded her of the pictures she had seen of the Mt. Vesuvius eruption. Massive amounts of debris “flew up from the center [of the fort] and seemed to stand still for a moment…then…pieces of steel, stones, and dirt, came rattling, and thundering down.” Frobel, like Bissell, was also in the line of fire; a stray shell exploded very close to her house, marked by a “little stream of blue smoke [which] came in one door and passed out the other.”

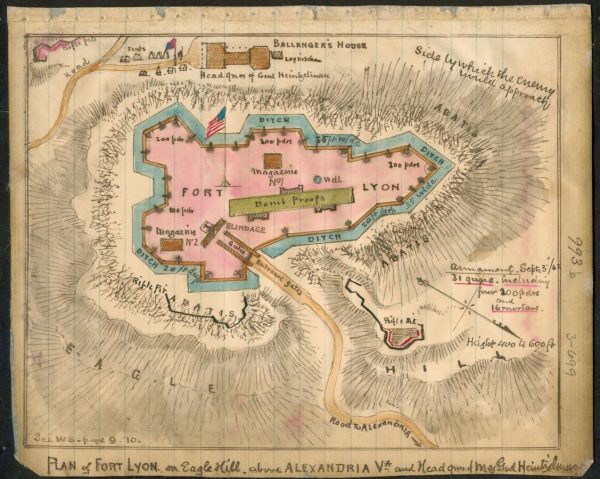

The massive explosion witnessed by Bissell and Frobel took place in the magazine of Fort Lyon, one of the largest forts in Washington’s defense system. A detail of twenty-six men from the 3rd Battalion German Heavy Artillery (New York)[1], commanded by a lieutenant, had been inspecting, airing, and refilling shells because moisture had dampened the powder and caused it to become caked into the shells. The men at first tried scraping the powder away using wooden spoons; when that didn’t do the trick, the officer thought it was a good idea to give the men priming wires to expedite the process. The lieutenant’s impatience proved disastrous. Friction from the priming wire probably caused a spark, igniting an explosion that set off the eight tons of powder and several thousand rounds of fixed ammunition in the magazine. The massive blast hurled debris, dirt, shells, and bodies hundreds of feet in the air. The concussion was so powerful that it shook houses and shattered windows in parts of nearby Alexandria.

“As soon as the shells stopped yelling around [his] ears,” Bissell raced back to the smoldering fort. Picking his way through the dust and debris, the Connecticut soldier witnessed a grisly scene at the explosion site – marked by a hole as large as his father’s barn cellar, Bissell thought. Scattered around the crater were the mangled bodies of dead and wounded men. The first man Bissell saw “lay with a hole as large as your fist in the top of his head.” The poor soldier’s body was “cut and mangled, his legs were broken and nearly torn off, both arms were gone and the skin nearly all torn away from what remained.” Another body was legless and had also been decapitated; the man’s head was later found some distance outside the fort. The poor lieutenant in charge of the detail, whose impatience caused the explosion, was so badly disfigured that he could only be identified by a piece of his shoulder strap. Newspapers reported that the explosion killed over twenty men and wounded nearly twenty others.

To his relief, Lewis Bissell discovered that most of the men in his own regiment were in their quarters at the time and were unhurt, but he still went down to the hospital to visit the wounded. “One was so badly wounded that his entrails came out,” Bissell wrote his father. “Another had the left side of his head blown away. The brains came out leaving a hollow space.” Still another had his hip mostly torn off by the explosion; Bissell thought the poor man was “riddled like a sieve.” Several of these most seriously wounded died before the next morning.

To his relief, Lewis Bissell discovered that most of the men in his own regiment were in their quarters at the time and were unhurt, but he still went down to the hospital to visit the wounded. “One was so badly wounded that his entrails came out,” Bissell wrote his father. “Another had the left side of his head blown away. The brains came out leaving a hollow space.” Still another had his hip mostly torn off by the explosion; Bissell thought the poor man was “riddled like a sieve.” Several of these most seriously wounded died before the next morning.

The next day, President Lincoln and Secretary of War Stanton made the trip across the Long Bridge from Washington to view the extent of the damage. The President pulled up to the gate of the fort in his carriage, stepped out, and walked around the camp “just as if he was at home,” Bissell thought. Lincoln even couldn’t resist picking up an axe lying around to “[show] the boys how he used to swing it.” The Connecticut soldier was on guard at the time, and told his father that he got a good look at the Commander-in-Chief as he passed by. “He is very tall and slim,” Bissell wrote, “stoops a little, [and] has a very keen, quick, and shrewd look about his eyes.” The President and his party got back into the carriage and made their way back across the Potomac after about an hour’s stay. At 4:00 pm, a funeral procession, consisting of seventeen ambulances and accompanied by mournful music from the 1st Connecticut Heavy Artillery band, made its way out of the fort and rumbled toward the Soldiers’ Cemetery (now the Alexandria National Cemetery). For the men guarding Washington, the brief terror and excitement was over. “Since then,” Bissell told his father, “things have been very much as usual.”

______________________________________________________________

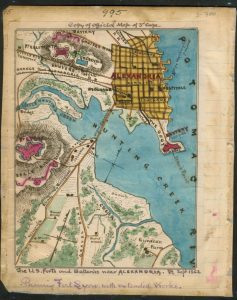

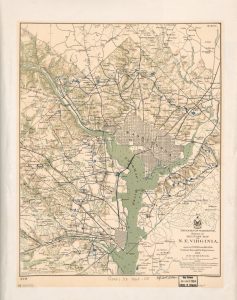

Fort Lyon, one of the sixty-eight forts and batteries built during the Civil War to protect Washington, D.C., was the main work designed to guard the heights south of Hunting Creek. If a Confederate force gained that high ground, it could easily shell the city of Alexandria. Named after Brigadier General Nathaniel Lyon (killed at the Battle of Wilson’s Creek, Missouri), the fort was the second-largest work in the system and covered an area of nine acres, with a perimeter of 937 yards. It had emplacements for forty guns, and its armament consisted of ten 32-pounders, ten 24-pounders, seven 6-pounders, two eight-inch mortars, and four 24-pound Coehorn mortars. No visible remains of the fort exists today; its site is now occupied by the Huntington Metro station. For more information of the Civil War Defenses of Washington, please visit: https://www.nps.gov/cwdw/index.htm.

In May 1864, Grant pulled Lewis Bissell and his regiment, the 2d Connecticut Heavy Artillery, from fort duty and sent them to the Army of the Potomac to make up for losses in the Overland Campaign. Converted to infantrymen, their first action was at Cold Harbor, where they suffered 323 casualties. The regiment fought with the VI Corps for the remainder of the war at Petersburg and in the Shenandoah Valley. Lewis Bissell survived the war and lived until the age of 93.

Nathan Marzoli is a historian at the U.S. Army Center of Military History in Washington, D.C., where he specializes in unit history and leads staff rides to Civil War battlefields. He has a BA and MA in History from the University of New Hampshire. His publications include “‘Their Loss Was Necessarily Severe:’ The 12th New Hampshire at Chancellorsville,” and “‘We Are Seeing Something of Real War Now:’ The 3d, 4th, and 7th New Hampshire at Morris Island, July-September 1863” (winner of the 2017 Army Historical Foundation’s Distinguished Writing Award). He is currently working on a study of substitutes in the Union army.

Sources:

Benjamin Franklin Cooling III and Walton H. Owen II, Mr. Lincoln’s Forts: A Guide to the Civil War Defenses of Washington (Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, Inc, 2010).

Mark Olcott and David Lear, The Civil War Letters of Lewis Bissell (Washington, D.C.: Field School Educational Foundation Press, 1981).

The Washington Evening Star. June 9-11, 1863.

Mary Holland and Dallas M. Lancaster, The Civil War Diary of Anne Frobel of Wilton Hill in Virginia (Florence: AL: M.H. and D.M. Lancaster, 1986) [excerpt accessed from the Fort Ward website, https://www.alexandriava.gov/historic/fortward/default.aspx?id=40044#1863].

[1] This unit became part of the 15th Regiment Heavy Artillery on September 30, 1863.

Thanks Nathan for sharing a off-the-battlefield story that I was not familiar with and I imagine is not widely known. It was a reminder that the gruesome human costs of war often extend beyond combat.