Railroads: Management in the War

As with much in the war, it’s not just advantages of more resources, but how they’re applied, that is important. Better railroad management was a key in Union victory.

Important advantages that the Union possessed included more railroad mileage (20,000 versus 9,000 in the Confederacy), more standard gauges, more connectivity in their network, and greater industrial capacity. In fact, the Confederacy had two states that were not even connected to the larger rail network: Florida and Texas. Gauge in particular (the distance between the rails) was an issue, as it varied throughout the South.

Yet simply having more resources is not enough. During the course of the war, Union leadership consistently managed its railroads better. Starting in January, 1862, President Lincoln was given the authority to take over operations of any railroad company for military use. His counterpart did not get that ability until February, 1865, far too late to do any good. In one example, the Confederate Secretary of War had to ‘request’ that North Carolina change a railroad gauge, which it refused. The Union Secretary of War could have ordered it done (and many examples exist of this happening).

Moreover, there was a greater spirit of cooperation among Northern railroad executives than was found in the South. Railroad companies like the Pennsylvania, Baltimore & Ohio, and others, were willing to work with the Federal government, and with each other, in ways that the private companies in the South were not.

The prevalence of State’s Rights politics is one reason why. The central government feared asserting its authority, and many companies and states refused to cooperate in operations that did not benefit them or might have adverse effects. For example, Greensboro, NC and Danville, VA, separated by only 50 miles, represented a gap in the Confederacy’s rail network. The two states argued over construction of the connection, and what gauge to use (each state had a different one). In addition to the lack of standard gauges, most southern rail lines were single tracked, inhibiting movement.

In much of the Confederacy, short lines built for moving crops to market were not conducive to moving troops or supplies over long distances. A spirit of competition prevented cooperation such as sharing cars or equipment or making connections. One Virginia rail executive noted, “We have lent the East Tennessee .. the use of our cars and engines .. and they have abused and broken them till we shall be very hard pressed for motive power and rolling stock to do our winter’s business”

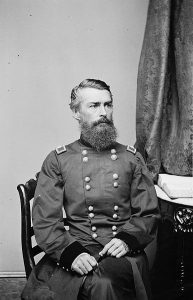

The Union established the United States Military Railroad, a branch of the military with the assignment of managing railroads. The USMRR would take over abandoned Confederate lines and operate them. The agency had repair crews who could respond quickly when needed. Civilians with railroad experience such as Daniel McCallaum (Erie Railroad), Herman Haupt (Chief Engineer, Pennsylvania Railroad), and Thomas Scott (Vice President, Pennsylvania Railroad), were hired to manage the USMRR.

Perhaps the most influential was Haupt. He established a set of rules that guaranteed efficiency:

-Not to allow supplies to be forwarded to the advanced terminus until they are actually required, and only in such quantities as can be promptly removed.

– To insist on the prompt unloading and return of cars.

-To permit no delays of trains beyond the time fixed for starting, but when necessary and practicable, to furnish extras, if the proper accommodation of business requires them.

The USMRR pulled off some great feats. On July 4, the day after the battle of Gettysburg ended, supplies were flowing toward the army at the battlefield, and wounded were being evacuated. At Petersburg, an entire railroad was built from scratch, 21 miles including a yard, telegraph line, turn table, and repair shops. Fifteen trains supplied the army with 1,400 tons of supplies a day. The best known accomplishment of the Union’s railroads was the transfer of the Eleventh and Twelfth Corps from Virginia to Tennessee to relieve pressure on Chattanooga. The journey covered 1,200 miles across eight states, included seven railroad lines, and moved 25,000 men in 12 days.

The Confederacy never created such a bureau, relying on the individual railroad companies to maintain and repair their track, and relying on voluntary cooperation with generals to move troops and supplies. It didn’t work.

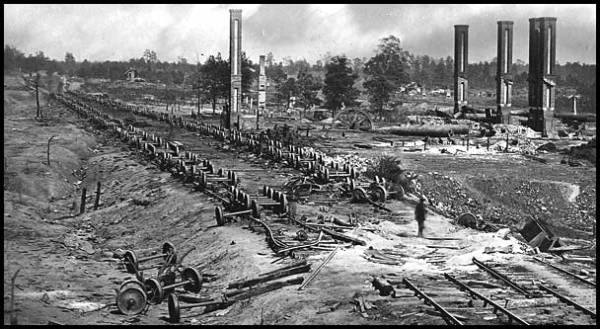

The Confederacy also never made maintenance of its railroads a priority. Richmond’s Tredegar Iron Works, for example, shifted almost entirely to military production (naval supplies, shells, cannons), abandoning its railroad products. In fact, not one new piece of rail was made in the entire Confederacy: Southern railroad companies cannibalized their system to keep the trains running: removing track from abandoned lines to where needed.

This tied into the Confederacy’s invasive military draft; by the end of the war drawing men aged 17-50. Railroads and other industries fought the government’s effort, arguing that skilled workers were more valuable to the war effort in their current jobs than shouldering a rifle. One frustrated company head wrote, “The government can take its choice, either have the men and let the road suffer, or leave the men alone and let the road be worked on…”

The lack of skilled workers, lack of supplies, limited rail repair facilities, lack of new equipment, and lack of maintenance all combined for a vicious cycle. By the end of the war, railroads in the Confederacy were worn out: tracks in disrepair, engines not maintained, and a fragmented system still largely divided.

It can’t be denied that the United States had much greater resources in regards to railroad operation at the onset of the war, yet its better management of railroads was key. Wrote one exasperated Southern rail official, ”Is it any wonder that transportation is deficient? Is it not rather a wonder that we have any transportation by rail at all?”

I can understand why southern railroads resisted in changing gauges. It was not a simple matter of moving the rails to the new gauge. The new gauge would no longer be compatible with your own equipment – locomotives and railroad cars. That would have been a nightmare to change your equipment. Great article.

Good points, thank you!

Something I have been curious about, is if there were any technology innovations during the war or embraced due to the war. Most improvements seem to have been operational. Railroad Operating Rules and signalling technology seem to go hand-in-hand. Was there anything like the block system in place?

Good question, Scott. I think most improvements were operational: scheduling, administration, etc. Union designers did create a machine that could twist rail to make it inoperable, and untwist rail to make it usable again. So far as I know there were no advances in locomotive technology, etc. I think both sides were pouring their energies into using the equipment that they had, rather than develop new technologies. I honestly can’t answer your question regarding the block system.

Many World War 1 historians refer to it as the first modern war. Sense at that point in my life I spent most of my time reading about World War II, specifically the Eastern Front I took it as truth. After spending roughly the last decade though reading everything I can on the American Civil War I have no clue why so many historians refer to World War as the first modern war. They used Telegraph lines, they used highly accurate rifles, obviously they dug trenches, head highly accurate artillery, but more to the point of your article trains we’re extremely important especially in moving troops from one area to another quickly and the problems they encountered with everything from different gauges to sabotage. Anyone let’s read the most basic book about Petersburg could have told you 50 years later how World War 1 was going to turn out. It was an exceptional article on the problems specifically the southerners faced and keeping their trains running very enlightening and interesting at the same time. Thank you for the great article

Thank you for your thoughts and comments!

‘An army travels on its belly’. The North was far superior in keeping their forces supplied, even while occupying territory that was often deep within the Confederate borders. The South couldn’t do that, even though it was THEIR own land. The railroad situation had everything to do with that. The Union organization and ‘approach’ behind the lines was, in my mind, the real difference in deciding the war’s outcome.

I agree totally! Thanks!