The Grinch of St. Joseph, Missouri

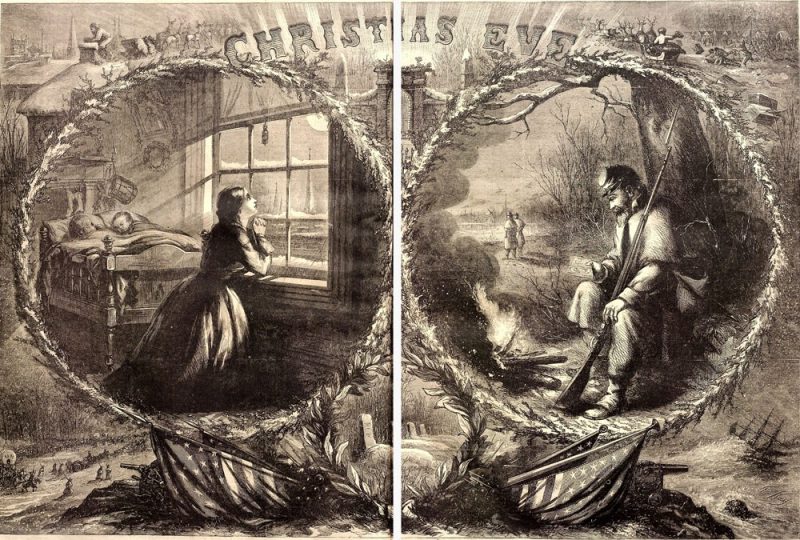

Nearly 100 years before the 1957 classic Dr. Seuss book appeared on the shelves, there was another Grinch who lived in the frontier town of St. Joseph, Missouri during the Civil War. Typically, we think of Christmas during the Civil War in a duel lens for Americans. The holidays provided soldiers a respite from combat, while it also highlighted homesickness and reflection over the meaning of war. We also look to the fabled stories of fraternization along the Rappahannock River between Johnny Reb and Billy Yank, as they exchanged gifts and temporarily forgot they were enemies. Yet, there are still documented stories that do not necessarily fit into that mold.

On January 1, 1863, an op-ed appeared in The Weekly Herald and Tribune, a newspaper in St. Joseph. An anonymous civilian in the town did not believe in good cheer. He saw that Christmas “is not the sacred day with us that is in extreme Eastern cities, where the Roman Catholic is the prevailing religion.”

On Christmas Eve, he notes, people in town celebrated “by the popping of small guns, the booming of miniature cannon, the blaring of bonfires, the whizzing of rockets, and the vigorous blowing of sundry burns.” He even went so far to criticize “Santa Claus,” who was in the process of giving treats to children when all-of-a-sudden “it thundered, it rained, it lightened, it grew pitchy dark . . . it really seemed that a foretaste of the infernal regions was furnished us.”

St. Joseph’s Grinch ended his article by petitioning that “Christmas is an expensive institution and should be abolished by the present General Assembly.”

Now, we may look at this anonymous writer as simply a “Grinch” or a “Scrooge,” who hated Christmas, but we also should look at the life of St. Josephites in 1863 to understand why. The westernmost city in the United States accessible by rail, St. Joseph was an important town for both sides and was certainly not immune to fighting. In fact, in 1861 alone, the town’s Pony Express had halted, United States troops from Fort Leavenworth had occupied it, guerrillas sacked and looted the town, a railroad bridge over the Platte River was destroyed, martial law had been declared, and earthworks were built around the town.

Perhaps, we can sympathize with the Grinch and with the civilians celebrating. On one hand, civilians had a reason to celebrate. That year, the dueling armies had left the region, and Union troops had kept the peace compared to the previous year. But for the Grinch, war was still raging in his home state, the town was still occupied, and the future was uncertain. As we know, the war would go on for another three long bloody years.

Too bad that, as is the case even today, The Grinch and others could not see Christmas for what it truly is: A Celebration that Something better can be upon and among us, if only we are open to it.

Wishing everyone, soldiers and civilians, a peace-filled Christmas this year.