The Abolition of Debt Peonage Slavery in New Mexico Territory, Part 2

Emerging Civil War welcomes back Ray Shortridge for Part 2 of his study on slavery in New Mexico territory during the antebellum and Civil War years.

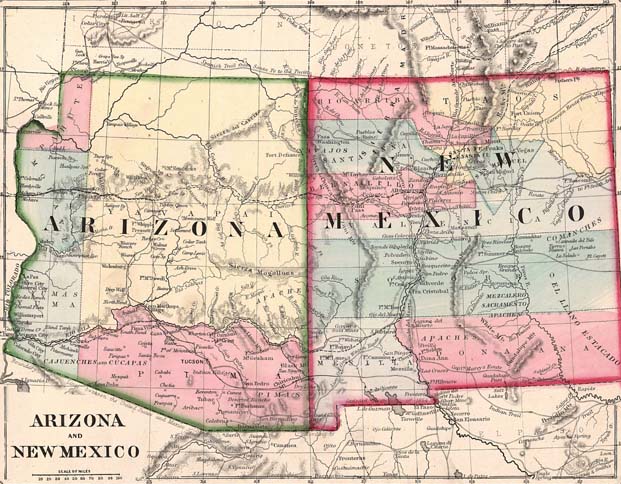

Initially, the influx of Americans into New Mexico provided an incentive for the Ricos to increase the number of peons they held in bondage. Manufactured goods and luxury items imported down the Santa Fe trail were of better quality and less expensive than those brought north from Mexico. To pay for these imports, Ricos increased the number of flocks of sheep and the number of debt peons to shepherd them. Navajo families wove the wool from their flocks into blankets for the American market. In a few years, New Mexico edged into the commercial capitalist economy of the United States.

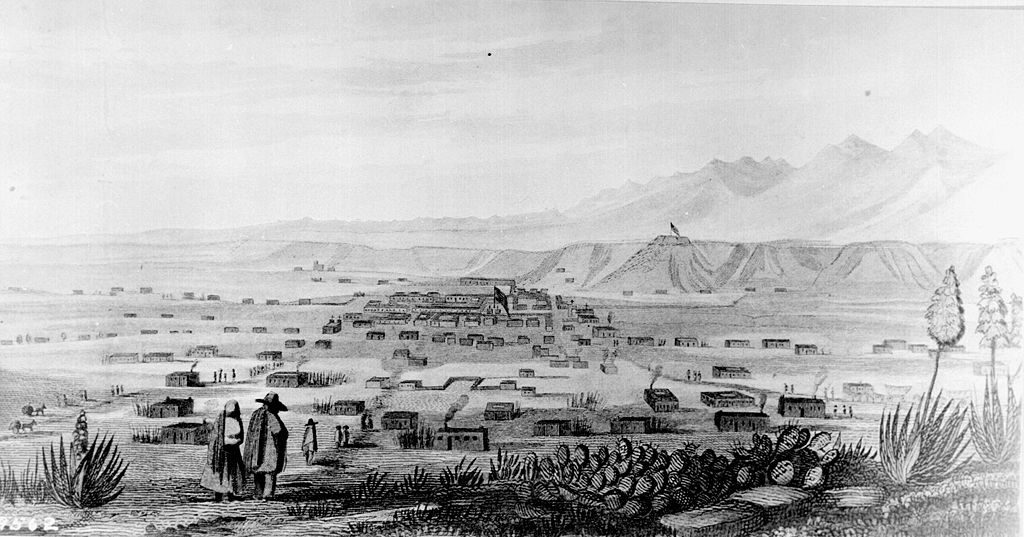

Americans set up shops in Santa Fe, and some enterprising Ricos traveled as far a Philadelphia to purchase products at wholesale. The Ricos, along with American merchants, then transported their wares down the Santa Fe Trail to New Mexico and, also, further south to Chihuahua for the Mexican market. The American conquest of New Mexico resulted in a growing market for mutton, fodder, blankets, and grain within the Territory to supply the army posts and also to the Colorado mining towns. As a result, the Ricos continued to add to their flocks and the number of debt peons that they held in bondage. In 1851, the Ricos in the territorial legislature passed a “Law regulating contracts between masters and servants” that tightened the control that landowners had over their peons.

The Republic of Mexico banned the institution, but the government lacked the will and capacity to enforce the prohibition in New Mexico, fifteen hundred miles to the north. However, as the United States tightened its grip on its new territory, Americans in the territorial government began to cast a jaundiced eye toward debt peonage. The strident political controversy relating to chattel slavery in the South turned a spotlight on the bondage practiced in New Mexico that resulted in the elimination of two key elements of the practice.

In 1857, Chief Justice Kirby Benedict held in the case of Jaremillo v. Romero that a minor could not be held in service for a parent’s debt. Kirby pointedly remarked on the chicanery commonly perpetrated between Rico masters and local magistrates, who were also Rico landowners.[1] The Romero decision outlawed perpetual servitude of successive generations of a family doomed to debt peonage in order to pay off the original debt. Justice James J. Deavenport further shielded minors in ruling that a minor, whose mother was held in bondage as a debt peon (and whose father was the mother’s master), could not be held in servitude as a consequence of her mother’s peonage status.[2]

The 13th Amendment proclaimed the end of “slavery or involuntary servitude.” Nuevo Mexicano Ricos argued that this did not apply to their servants because debt peons entered their service voluntarily. Radical Republicans persuaded President Andrew Johnson that debt peonage was a disguised form of slavery, and Johnson mandated its suppression. However, this had little effect in ending the practice. The federal government had to rely on the army to suppress debt peonage, but it was focused on fighting Indian marauders who had become more active after troops were withdrawn to fight rebels in the east. Despite a Territorial Supreme Court ruling that peonage was involuntary servitude and contrary to the 13th Amendment, the peons lacked the language and monetary resources to challenge their masters in the courts.[3]

Radical Republicans were ideologically committed to ending unfree labor in any form and pressured Congress into passing the Peon Act in 1867. This law repeated the finding that peonage was involuntary servitude and levied penalties consisting of fines ranging from $1,000 to $5,000 or up to five years in prison. The law also charged all federal agencies, including the army and Indian Agents, to enforce the law. With this enforcement power, Nuevo Mexicano Ricos rapidly transformed their debt peons into a class of low wage earners, and the Abolitionists’ war aim to end unfree labor in the United States was finally accomplished.

Sources:

[1] Jaremillo v. Romero, op. cit.

[2] Marcellina Bustamento v. Juana Analla in Gildersleeve, Reports of Cases, 255–62. Cited in: William S. Kiser, “A Charming Name for a Species of Slavery: Political Debate on Debt Peonage in the Southwest, 18402s-1860s,” Western Historical Quarterly, Summer 2014, Vol. 45 Issue 2), 182.

[3] Tomás Heredia v. José María García, 26 January 1867, New Mexico

Territorial Supreme Court, both folder 36, box 3, U.S. Territorial and New Mexico Supreme

Court Records, NMSR. Cited in: William S. Kiser, op cit, 186.

Bibliography and Recommended Reading

Primary Sources

Kirby Benedict, Jaremillo v. Romero, 1857-NMSC-007, 1 N.M. 190 (S. Ct. 1857) .

Ross Calvin, ed., Lieutenant Emory Reports: A Reprint of Lieutenant W. H. Emory’s Notes of a Military Reconnoissance (sic) (Albuquerque; University of New Mexico Press; 1951.)

Condition of the Indian Tribes, 39th Cong., 2nd Sess., Senate Report No. 156 (Washington, DC; Government Printing Office; 1867).

- St. Geo. Cooke, The Conquest of New Mexico and California: An Historical and Personal Narrative (New York; G. P. Putnam’s Sons; 1878).

- W. H. Davis, El Gringo, or New Mexico and Her People (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1857).

Josiah Gregg, Commerce of the Prairies (Santa Barbara; The Narrative Press; 2001).

Lawrence Kelly, Navajo Roundup: Selected Correspondence of Kit Carson’s Expedition against the Navajo, 1863-1865 (Boulder; The Pruett Publishing Company; 1970).

The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, 128 Volumes, (Washington, D.C., 1880-1901), Series I.

John P. Wilson and Jerry Thompson, The Civil War in West Texas & New Mexico, The Lost Letterook of Brigadier General Henry Hopkins Sibley, (El Paso, TX, 2001).

Secondary Sources

James F. Brooks, Captives and Cousins: Slavery, Kinship, and Community in the Southwest (Chapel Hill; University of North Carolina Press; 2002).

Neil P. Chatelain, “Beyond the 13th Amendment: Ending Slavery in the Indian Territory,” (Emerging Civil War Blog; July 10, 2018.)

William S. Kiser, “A Charming Name for a Species of Slavery: Political Debate on Debt Peonage in the Southwest, 18402s-1860s,” (Western Historical Quarterly, Summer 2014, Vol. 45, Issue 2), 169-189.

Scott P. Marler, “Two Kinds of Freedom: Mercantile Development and Labor Systems in Louisiana Cotton and Sugar Parishes After the Civil War” (Agricultural History, Vol. 85, No. 2, Spring 2011), 225-251

Edward Royce, The Origins of Southern Sharecropping (Philadelphia : Temple University Press, 1993).

Mr. Shortridge: The articles were, for me, a really eyeopening examination of 19th Century Western history. I’m not that familiar with the development of the territories that were once possessed by Spain, then independent Mexico then the U.S. Is the story of the apparently widespread institution of debt peonage slavery recognized much, other than in the primary and mostly scholarly sources you cited? I’m curious, are there any National Parks or state parks out there that dedicate some of their interpretive exhibits to the topic? Do they teach about it in New Mexico’s public schools at all?

i am unaware of any federal or state parks/memorials and the like that present exhibits on debt peonage. i cannot speak to whether teachers cover this in k-12, but in response to your question, i reviewed the state’s standard’s for social studies and did not find a reference to it, so while some teachers might address this, it is not part of the required curriculum.

Thanks for poking around for answers to my questions. It’s a pity, in my opinion, that this part of the Southwest’s development– as unpleasant and repugnant as slavery– is forgotten history.