Two Union Veterans: The Election of 1880, Part 1

Ever heard the old joke that in order to be President of the United States after the Civil War, you only needed to be Republican, be a Union veteran, and have a beard? You can be forgiven for thinking it might be true. After all, look at the post-war presidents: Ulysses S. Grant (bearded Republican veteran); Rutherford B. Hayes (bearded Republican veteran); James A. Garfield (bearded Republican veteran); and Chester A. Arthur (mutton-chopped Republican veteran; still counts).

The country detoured to Grover Cleveland from 1885-89, who had the nerve to wear just a mustache AND be a Democrat. Cleveland was also not a veteran: he paid a substitute to take his place in the Union ranks during the Civil War. Bearded Republican veteran Benjamin Harrison ousted Cleveland and served 1889-93, only to lose his reelection bid in 1892 to… Grover Cleveland. We finished out the century with William McKinley, who was a Republican and a Union veteran but was also clean-shaven. McKinley was the last Civil War veteran to be president.

Most of these men either held political office or at least had political aspirations before the Civil War (excepting Grant), and they were usually not shy about allowing their political party to emphasize their service to the Union when running in postwar elections. Republicans were often quick to emphasize that they were the party of Lincoln, Union, and emancipation while Democrats were the party of slavery, secession, and rebellion. This tactic of “waving the bloody shirt” served Republicans well in many elections after the Civil War. It helped that Democratic presidential candidates were usually not veterans.

In just one presidential election did BOTH parties nominate Union veterans to run for the nation’s highest office. The year was 1880, and Democrats smelled blood in the presidential waters. In 1876, Democratic candidate Samuel J. Tilden had won the popular vote but been denied the presidency due to electoral disputes in three “unreconstructed” southern states: Louisiana, South Carolina, and Florida. Congress created a commission to determine whether Tilden or Republican candidate Rutherford B. Hayes should receive those states’ Electoral College votes and be declared the election’s winner and the next president. In a party line vote, the commission awarded the votes to Hayes, who served as the nineteenth president from 1877-81. Hayes was not interested in running for a second term, so the Republicans needed a candidate in 1880. Many assumed they would select former President Ulysses S. Grant to run for an unprecedented third term. Though he stayed quiet publicly, Republican insiders knew Grant was willing to run again.

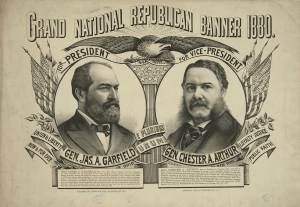

But when the Republicans held their nominating convention in Chicago, Grant faced stiff resistance from those opposed to a third term for anyone—even the most revered American general since George Washington. In fact, it was Washington’s example that had prevented any president from ever seeking a third term. Washington voluntarily walked away from power at the end of his second term in 1797, and nearly a century later, most believed that if two terms were enough for Washington, they were enough for anyone. Grant came close, but he was unable to win enough votes to secure the Republican nomination to run for president again. The party then looked for a compromise candidate, eventually settling on former Union major general and nine-term Ohio Congressman James A. Garfield. In fact, Garfield had been a vocal opponent of Grant running for a third term, but it was his nominating speech for another candidate—Treasury Secretary John Sherman—that made many in Chicago finally turn to Garfield, who was nominated on the thirty-sixth ballot.

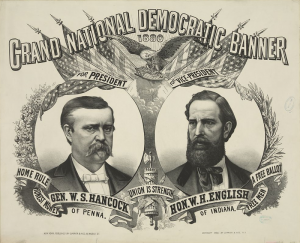

On the Democratic side, the real question facing the party before its convention in Cincinnati was whether or not Samuel Tilden would run again to claim the office Democrats believed had been stolen from him in 1876. Tilden played coy, both interviewing potential running mates but also telling many that his health would preclude him from running. The party eventually decided to move on to a field of potential candidates that included Senator Thomas Bayard of Delaware, Supreme Court Justice Stephen Field of California, former Indiana Governor Thomas Hendricks (Tilden’s running mate in 1876), and others. Bayard seemed to have the most support after Tilden became a non-issue, but the party soon turned to another candidate: General Winfield Scott Hancock.

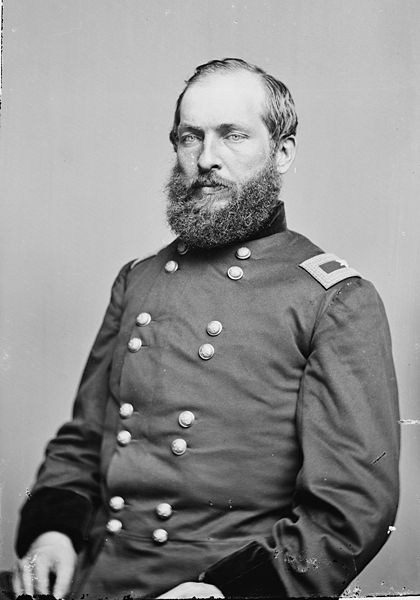

Hancock was one of the Union’s most celebrated and revered senior commanders during the Civil War. A West Point graduate and Mexican-American War veteran, Hancock spent much of the Civil War in command of the Army of the Potomac’s Second Corps. General George B. McClellan dubbed him “Hancock the Superb” in 1862, and the name stuck. Hancock’s most famous service was at Gettysburg, where his corps sustained the brunt of Pickett’s Charge on the battle’s third day, repelling the Confederates at the battle that many still consider the Confederacy’s “high tide.” Hancock moved calmly on horseback among the Second Corps’ lines during the pre-assault cannonade and during the infantry assault and was severely wounded by a bullet that lodged in his groin. This wound would pain him for the rest of his life.

Hancock stayed in the Army after the war, serving in a number of assignments. A native of Pennsylvania, he was a lifelong Democrat with well-known political ambitions. Previous Democratic conventions had considered him as a potential presidential candidate, and Hancock, despite no previous elected experience, did not disavow anyone of his interest in the office. His status as a Union hero was particularly appealing to Democrats tired of being beaten over the head by old charges of disloyalty and sympathy with secession. But it was Hancock’s brief time as commander of the postwar Fifth Military District, covering Texas and Louisiana and headquartered in New Orleans, that made him particularly appealing to southern Democrats. Upon arriving at his new post in late 1867, Hancock issued orders clearly supporting the Reconstruction policies of President Andrew Johnson, which included returning as much civil power as possible to white men and having the Army take a back seat. Republicans and black Americans realized that this equaled a return to antebellum white supremacy. President Johnson praised Hancock’s action, while Republicans and African Americans condemned it. Hancock was transferred after Ulysses S. Grant became president, but his actions in New Orleans made him an attractive candidate to conservative white southern Democrats in 1880.

To be continued…

Love the “Aftermath of War” politics! Thanks.

This has always been one of the most interesting elections to me. Knowing the dynamics between Hancock and Grant during the Overland Campaign, and then seeing them on opposite sides of this election, has raised lots of questions for me. I’m eager to read more!

Love this write-up so far. As a side note, 1896 also featured two Union veterans (Republican McKinley and Gold Democrat John M. Palmer) in a three-way race with William Jennings Bryan.