The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion

When it comes to primary resources regarding Civil War medicine, one of the best sources available to researchers is the The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion, 1861-1865. The history grew out of what was known as Circular No. 2, passed on May 21, 1862, and Circular No. 5, passed on June 9, 1862.

When it comes to primary resources regarding Civil War medicine, one of the best sources available to researchers is the The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion, 1861-1865. The history grew out of what was known as Circular No. 2, passed on May 21, 1862, and Circular No. 5, passed on June 9, 1862.

Circular No. 2 was passed by Dr. William Alexander Hammond, a military physician, neurologist, and Surgeon General of the United States from 1862-1864. The circular established the Army Medical Museum for the purpose of “illustrating the injuries and diseases that produce death or disability during war, and thus affording materials for precise methods of study or problems regarding the diminution of mortality and alleviation of suffering in armies”. It directed medical personnel to collect and forward to the Surgeon General all specimens of morbid anatomy regarded as valuable, along with any projectiles and anything else that may be as useful for the study of military medicine or surgery. This incredibly significant directive created an unprecedented amount of specimens for study on a scale never before seen in American medicine and allowed for the opportunity to develop new ideas about medicine and disease.

As the circular spread, many doctors wanted to get involved and participate for not only did it create the opportunity for new medical studies, but it also created the opportunity for doctors to advance their careers. For example, Dr. Jacob Da Costa, a civilian doctor treating ill soldiers in Philadelphia, was able to submit his studies about new techniques to diagnose diseases. Additionally, Dr. Samuel Gross, Chair of Surgery at the Jefferson Medical College, was able to use the circular to study the effects of camp diseases on surgery.

This plethora of medical information available was only compounded by Circular No. 5 passed just a few weeks later that required medical officers to submit reports with all specimens sent to the museum. This included “sanitary, topographical, medical and surgical reports, details of cases, essays and the results of investigations and inquiries as may be of value…” By the end of the war the enormous amounts of reports and images were available for study and they were initially published by the Surgeon General’s Office in Circular No. 6, on November 1st, 1865. The circular titled, Reports on the Extent and Nature of the Materials Available for the Preparation of the Surgical and Medical History of the Rebellion. However, the issue with this circular was that it was only a 165 page synopsis of the information available. So under the direction of the Surgeon General, a more inclusive report was to be published over the next several years.

This plethora of medical information available was only compounded by Circular No. 5 passed just a few weeks later that required medical officers to submit reports with all specimens sent to the museum. This included “sanitary, topographical, medical and surgical reports, details of cases, essays and the results of investigations and inquiries as may be of value…” By the end of the war the enormous amounts of reports and images were available for study and they were initially published by the Surgeon General’s Office in Circular No. 6, on November 1st, 1865. The circular titled, Reports on the Extent and Nature of the Materials Available for the Preparation of the Surgical and Medical History of the Rebellion. However, the issue with this circular was that it was only a 165 page synopsis of the information available. So under the direction of the Surgeon General, a more inclusive report was to be published over the next several years.

When originally published, the six enormous volumes were printed by the United States Government Printing Office every few years between 1870 and 1888, mostly under the direction of Dr. Joseph K. Barnes. At the time, people realized the importance of this medical information for not only does it make some sense of the chaos of four years of war, it could provide a wealth of knowledge for future generations. For example, a letter from Dr. Edward H. Smith to Dr. Hammond in 1863 reasoned, “if there is any benefit from the sad struggle of the age, it is that medical officers can fully justify looking for information and present the information for the world’s future use..”

When originally published, the six enormous volumes were printed by the United States Government Printing Office every few years between 1870 and 1888, mostly under the direction of Dr. Joseph K. Barnes. At the time, people realized the importance of this medical information for not only does it make some sense of the chaos of four years of war, it could provide a wealth of knowledge for future generations. For example, a letter from Dr. Edward H. Smith to Dr. Hammond in 1863 reasoned, “if there is any benefit from the sad struggle of the age, it is that medical officers can fully justify looking for information and present the information for the world’s future use..”

Even 131 years later, medical personnel and historians still utilize the information presented in The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion. Granted, it is not all inclusive for many of the Confederate records were destroyed by the end of the war. However, the images, cases, statistics, and analyses in a now fifteen volume set provide not only primary accounts into the suffering endured during the Civil War, but the advancements that became of it.

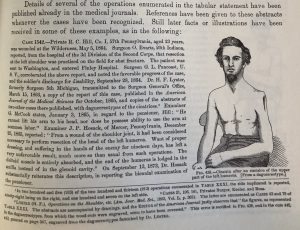

For those interested in exploring this expansive primary resource, it has been digitized and can be found in numerous collections at the U.S. National Library of Medicine as well as at Internet Archive. Yet beware, some of the descriptions and images are not for the faint of heart. *All images were taken by author from the primary source.

Medical and Surgical History is not for the faint of heart. Privacy issues today would prohibit the gathering and photography soldier wounds.

There are famous people within the pages. For instance, Part II, Vol. II, Chap VII, Section III p. 363 is about “Injuries of the Genital Organs” of one “Colonel Joshua L. C—–, 20th Maine.”

As I worked my thesis on military medicine, I began to notice a change in the way I saw the images of injured men. I did not become innurred to them–rather I began to see them as images of facts related to those who had been ill or injured, and only that. The men were never diminished by their wounds or conditions–they simply were soldiers who served. As I worked from the Rev War up through modern injuries in Afghanistan, I became even more used to looking at these images. At some point I realized that I no longer flinched from burned faces or amputated limbs–I had learned to see the person, not the wounds.

I add this because we still see plenty of injured military folks in our daily lives. We see them on TV, we elect them to office, we shake their hands or touch their shoulders as we visit hospitals or do other volunteer work with our living vets. The more I look at the images of wounds, the less they repulse me and the more accepting I have become of the wounded in my midst. We should not be repelled by them, afraid of them, or turn away from them. We should learn to love them again and see them as humans.

This lesson was one of the biggest take-aways I got from my thesis work, and I am better for it.