Symposium Spotlight: Fort Stevens

Welcome back to another installment in our continuing Symposium Spotlight series. Over the last several weeks we have been giving you a sneak peak look at the presentations our presenters will deliver in August. Continue to follow the series and discover some of the research our presenters have uncovered, themes that they will be exploring at the symposium, and insight into these “Forgotten Battles of the American Civil War.” This week Steve Phan looks at Fort Stevens.

Welcome back to another installment in our continuing Symposium Spotlight series. Over the last several weeks we have been giving you a sneak peak look at the presentations our presenters will deliver in August. Continue to follow the series and discover some of the research our presenters have uncovered, themes that they will be exploring at the symposium, and insight into these “Forgotten Battles of the American Civil War.” This week Steve Phan looks at Fort Stevens.

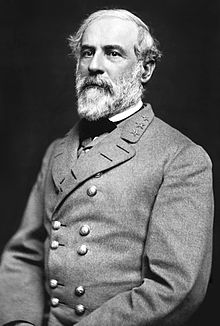

Fortress Washington was under siege. Three years of extensive construction, expansion, and training—all at the expenditure of exorbitant resources—had come down to a race. The Confederate Army of the Valley District, commanded by Lt. Gen. Jubal Early, advanced south along the Rockville-Georgetown Pike on the morning of 10 July 1864. The day was hot and humid, and dust covered the road as the exhausted rebel force aimed to complete their campaign by seizing the Federal capital. General Robert E. Lee’s “Bald Old Man” was running out of time. The previous day, Early’s infantry and cavalry columns unexpectedly ran into heavy Federal opposition along the Monocacy River on the outskirts of Frederick, Maryland. Token Resistance was expected, however. Elements of the Federal Middle Department (8th Army Corps) commanded by Major General Lew Wallace operated in the area for several days. Wallace cobbled together a hodgepodge mix of rear-echelon, garrison, and part-time troops to engage Early long enough for reinforcements to arrive on the field, and most importantly, to secure Baltimore and Washington. Support appeared on the waterways. The Federal high command outside Petersburg, Virginia at last responded to ominous reports of a large Confederate force operating in the Shenandoah Valley and advanced north into Maryland Wallace’s prospect of delaying Early improved dramatically with the arrival of veterans from the Army of the Potomac. Brigadier General James B. Rickett’s 3rd Division 6th Corps led the vanguard of reinforcements dispatched from the trenches of Petersburg. It was Rickett’s division that Early’s collided with on the morning of 9 July, turning a minor action into a major pitched-battle. The blue-clad defenders, outgunned and undermanned—a rare occasion for Civil War battles—retreated in disorder toward Maryland after an 8-hour fight. As a result, recalled one of Early’s division commanders, Major General James B. Gordon: “The way lay open to Washington.”

Awaiting the Confederate army was one of the most heavily fortified cities in the world. By summer 1864, the elaborate defensive system encircling Washington D.C. comprised 60 forts, 93 detached batteries, 5 blockhouses, fortified bridges, over 30 miles of military roads, and armament massing 800 cannons. Supplementing the defenses was a garrison of over 30,000 men. The capital defenders comprised heavy artillerist—expertly trained to operate the large caliber artillery pieces mounted in the forts—together with a mix of infantry and cavalry regiments. Nominally, such a heavy force entrenched in fortified positions made an enemy advance on Washington D.C. foolhardy and desperate. But 1864 called for desperate measures by both the Union and Confederacy.

General Ulysses S. Grant’s relentless Overland Campaign brought Union armies to the gates of Richmond and Petersburg by July 1864. The cost was fearful: 50,000 casualties The general-in-chief looked to the Defenses of Washington to replenish his depleted ranks. In May and June, the War Department, with President Abraham Lincoln’s approval, transferred over 20,000 heavy artillerist to the front. The heavies replaced their sponge rammers with rifles and joined the veterans in bloody engagements throughout the summer. Their transfer revealed Lincoln’s evolution as commander-in-chief. For the war’s first three years, the War Department, at the administration’s behest, required a large, permanent garrison to secure the capital. With war-weariness reaching a fervor and his reelection in doubt, Lincoln pushed all chips to the center of the table, aiming for end the war in 1864. The Confederate army was keenly aware of the military and political implications as Grant’s armies advanced in unison across the landscape. Pinned against Richmond, the Confederate capital, and Petersburg, the critical railroad center 20 miles south, General Robert E. Lee desired to alter the strategic monument and release pressure on his lines by sending a force north. The task fell to Jubal Early, who was tasked with clearing the Federal army operating in the Shenandoah Valley, and from there, if the conditions ripe, advance north into Maryland and threaten Baltimore and Washington. Early’s campaign began in mid-June. By the second week of July, the Confederate army was at the gates of Washington.

The mighty Defenses of Washington played host to the invaders. Replacing the heavies in the lightly manned forts was a unorganized mix of secondary soldiers and civilians, and included the Veteran Reserve Corps (formerly Invalid Corps), 100-Days National Guard units, impressed government clerks, and civilian volunteers. At 1:30 pm on 11 July 1864, the signal station at Fort Stevens reported to headquarters in the city that the Confederate army was within 120 yards of their position. Just an hour earlier, Federal reinforcements arrived at the 6th Street Wharves on the Potomac.

Could the defenders hold the Confederates off long enough for support to arrive? President Lincoln sure hoped so. As Federal troopers disembarked from their transports, he reportedly uttered that their services were needed and that time was pressing: “You can’t be late if you want to get Early.” The soldiers responded with laughs and cheers, and marched with enthusiasm up the 7th Street Road. Up ahead lay Fort Stevens and the Confederate army. The finish line was in view.

Have you purchased your 2019 Emerging Civil War Symposium tickets yet? If not, head on over to your 2019 Symposium webpage and get yours today!

My wife and I on a late Summer’s Sunday afternoon paid a visit to Fort Stevens a few years ago. The Fort itself is now in the center of D.C.’s urban sprawl and I found it somewhat difficult to get a feel for what it was like to be at this very spot in the Summer of 1864 when the events in question were dramatically occurring. Nevertheless, the Park Service has done a good job in attempting to rehabilitate the grounds with a small open field in front of the earth works that outlined the Fort’s original design. Kudos for their efforts in attempting to preserve a little known and overlooked, but still a very important historical event of the Civil War.

Mr. Romans,

I’m glad to hear of the visit you and your wife paid to Fort Stevens. I grew up in the Brightwood neighborhood surrounding the remains of the fort. The house my family lived in is less than a five-minute walk from the the site.

Ever since I can remember, I’ve had a strong interest in American history and the Civil War in particular. I have no idea where it came from because none of my family shared my interest. A lot of things about the past I learned on my own and none of the public, private or Catholic DC schools I attended ever taught me anything about the only Civil War battle to take place in the District of Columbia. Nor did they teach us that at one time, the area you describe as “urban sprawl” was a place known as Washington County, DC. I can understand if it’s hard for you to imagine a battle taking place where rows of houses, paved streets and commercial development now stand. Just the same, it’s hard for me to look at the area I grew up in and imagine cows, pigs and fields of crops with a farmhouse here and there. I never got the sense from anyone I knew growing up that they knew anything about the rural past of the neighborhood. I personally can’t even recall seeing people spend time at Fort Stevens or Battleground National Cemetery before I visited those places on my own.

Anyway, as my knowledge of the war increased, I was well aware that a Civil War battle had taken place at Fort Stevens. But it still took time to realize the battle took place all over that area of DC and not just the confines of the fort. The battle stretched out into Silver Spring, Maryland… another rural place that also existed during the battle but was developed, commercialized and paved over. Suburban sprawl, if you will. I think historic preservation is absolutely important and I wish more of the 68 forts and batteries of the Civil War Defenses of Washington could have been preserved. But I also think the growth of the DC Metro area was inevitable. That said, there are still a lot of things one can learn from the remains of Fort Stevens and the CWDW. If houses and businesses now stood where the fort is, it would be even harder to connect with the site and there would likely be a never-ending debate about where the fort was. While you were there, did you realize that you were five miles north of the White House and the Capitol building? Imagine if Jubal Early and his invading army had taken control of the long-range guns of Forts DeRussy and Slocum, which flanked Fort Stevens and if they opened fire on Washington City? This would have been 50 years after the British burned the city. What would a successful bombardment have said to England and France about the chances of the Confederacy in achieving their independence?

I could go on with all of this but I will wrap it up by saying that I am a board member of the Alliance to Preserve the Civil War Defenses of Washington. We are about educating the public on this very important Civil War history. We offer bus tours of the remains of the CWDW forts and we tour the Monocacy battlefield as well. We also host Fort Stevens Day every second Saturday in July in partnership with the National Park Service. Please come visit again someday.