The Ravages of Spring: Elmira’s POW camp swamped by Chemung River

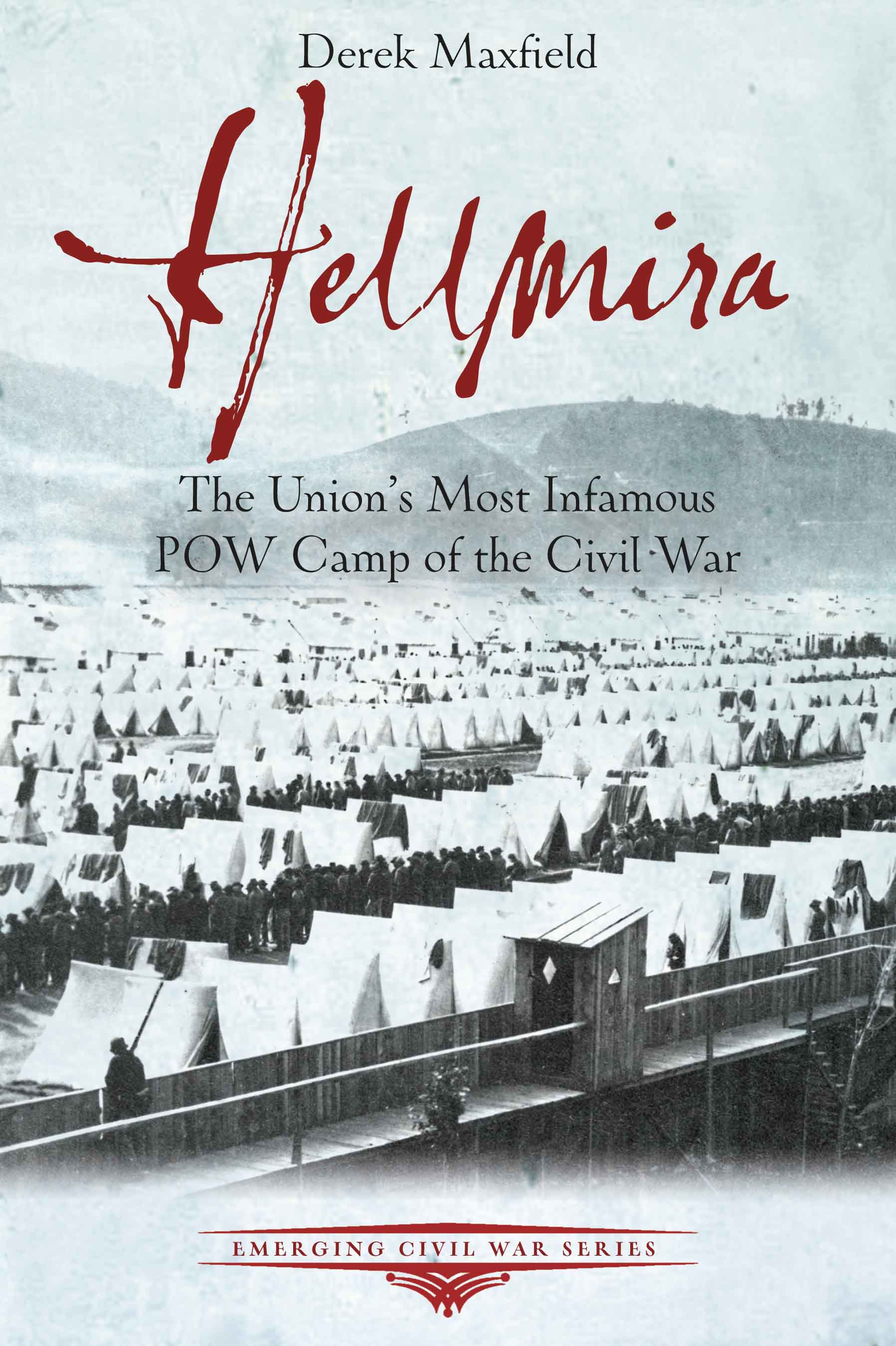

Since receiving the cover art of my first book, HELLMIRA: The Union’s Most Infamous POW Camp of the Civil War, I have been waiting not-so-patiently for the right opportunity to announce my book to the world.

The time has arrived.

Hastily constructed, poorly planned, and overcrowded, prisoner of war camps North and South were dumping grounds for the refuse of war. An unfortunate necessity, both sides regarded the camps as temporary inconveniences—and distractions from the important task of winning the war. There was no need, they believed, to construct expensive shelters or provide better rations. They needed only to sustain life long enough for the war to be won. Victory would deliver prisoners from their conditions.

As a result, conditions in the prisoner of war camps amounted to a great humanitarian crisis, the extent of which could hardly be understood even after the blood stopped flowing on the battlefields.

Hellmira contextualizes the rise of prison camps during the Civil War, explores the failed exchange of prisoners, and tells the tale of the creation and evolution of the prison camp in Elmira. In the end, the book suggests that it is time to move on from the blame game and see prisoner of war camps—North and South—as a great humanitarian failure.

By way of shamelessly plugging my book, I thought I would share an episode from the story: the great flood of March 1865.

The winter of 1864-65 was brutal. The first snow appeared in October and snow covered the ground more or less continually until those fateful days of March. The prisoners from the deep South suffered the most, though all felt the effects of Mother Nature’s wrath.

Warned to prepare for the rise of the river in spring, post commander Col. Benjamin F. Tracy contemplated abandoning the lower camp and adjusting the walls of the compound. Nothing came of that, probably because Brig. General William Hoffman, Union Commissary-General of Prisoners, would not bear the expense. Mother Nature followed up a historic winter with a spring thaw of awesome proportions. The resultant flood inundated the entire camp and caused prisoners in their barracks to the upper berths, staring down at four feet of brown water in some places. Tracy no doubt considered a full on evacuation of the camp.

A rigorous evacuation of the smallpox hospital was undertaken to rescue the poor souls stranded on what had been a spit of land next to the river. Make-shift rafts were quickly assembled and floated down from the upper camp. Once loaded, they were pulled back up to the main camp with ropes, fellow prisoners supplying the manpower. “The work was so strenuous,” Gray wrote, “that relay teams changed every other trip and were rewarded with whiskey for their efforts.”[1]

Reporting to Hoffman, Tracy outlined the disaster emphasizing that no prisoner had escaped, no building or property lost. About 2,700 feet of compound fence had been destroyed by the river and would need to be rebuilt, though this time with flood gates. The smallpox patients were housed in old dilapidated barracks that had been abandoned. While the situation had been bad, complete disaster had been averted.[2]

Recovery after the flood was slow. Prisoners battled mud and muck – and the occasional dead fish or eel. The camp fence was mended within weeks. Spring arrived, finally, and the tress of the valley again wore green. Those that survived the winter, then the flood, probably wondered at the achievement and hoped that they would not still be residents when the snowflakes began to fall again. A prisoner from the Lone Star state expressed it this way: “If ever there was a hell on earth, Elmira prison was that hell, but it was not a hot one.”[3]

_________________________________________________

Look for Hellmira: The Union’s Most Infamous POW Camp of the Civil War to be available sometime in the Summer of 2019. Amazon is taking pre-sale orders now, so folks can reserve a copy in advance.

Sources:

[1] Gray, The Business of Captivity, 62.

[2] OR, series II, vol. VIII: 419.

[3] Gray, The Business of Captivity, 142.

Professor Maxfield

In an age when the average person can name only Andersonville, your work on Elmira is welcome and timely. Every Prisoner of War camp or compound was interesting in its own way, and there is as yet no Master List of the dozens of POW facilities that existed during the War of the Rebellion. The plight of War Captives, North and South, is deserving of long overdue attention. Thank you for your significant contribution to the discussion.

Regards

Mike Maxwell

Mike,

Thanks for your comments. It is a very important and often overlooked subject. I hope my book helps to rectify this.

D. Maxfield

For family reasons my wife and I made the drive from Washington to Rochester often. After one-too-many trips up 15/390 we decided to take a more scenic drive and went through Elmira. Interesting town and also site of Mark Twain’s grave. That graveyard is right next to the old POW camp and state prison so we went over to check it out. The interpretive markers there made a it a point to explain that the confederate graves there were well-maintained and after the war the deads’ relatives elected to leave them there.

I used to live near Camp Parole in Annapolis, MD. Another interesting part of the POW system. A major problem was that the parolees, claiming the terms of their paroles, refused to do any work (and officers refused to provide any supervision). Eventually Hoffman wised up and provided a permanent garrison to maintain order. Parolees dried up but after the release of union POWs from Andersonville many of them were processed through Camp Parole. Annapolis National Cemetery in downtown is the final resting place for many.

Scott

Thank you for breaching the topic of the Parole Camp (of which Annapolis was one of about half a dozen put to use by the Union.) The typical flow path of a Federal soldier who surrendered to the enemy was as follows: disarmed — nature of any wounds determined (those unable to march were left behind at Shiloh, for example) — removed to the rear of Rebel lines — personal details recorded and soldier’s unit identified — placed in confinement — held in confinement until opportunity for Parole presented (Paroled Union prisoners agreed, on their oath, under penalty of death if caught violating that Parole agreement, to “not fight, or provide ANY military assistance to Federal forces, until properly EXCHANGED — captured Union soldier is paroled (officers mostly sent Home to await notice that their proper Exchange has taken place; after July 1862 enlisted men in Federal service confined in Parole Camp until notified of their proper exchange) — Exchange takes place (captured Union soldier, on his parole is swapped for a Confederate prisoner of equal rank… or in accordance with a formula, through which a solitary man of high rank was swapped for numerous enemy prisoners of lower rank) — Captured Union soldier is notified that he has been properly exchanged (his status changes from Paroled Prisoner, to Soldier on Active Duty, no longer bound by Parole oath restrictions) — the Exchanged prisoner (now simply another soldier on active duty) returns to his unit and resumes the fight.

The nature of Parole Camps (rarely used by the South; and never used after the Civil War) is one more topic deserving of discussion…

Cheers

Mike