Eliza Griffin Johnston: To Bravely Meet Danger and Tragedy

News traveled slowly, likely a frustrating fact for Eliza Griffin Johnston. However, one spring day in 1862 news arrived in California that changed her life. A battle thousands of miles away and weeks in the past had altered her plans, crushed her hopes, and taken the love of her life. She probably received the first news by private correspondence – maybe on black edged stationery. Before long, the news had been printed publicly on the pages of the Los Angeles Star. Under the heading “News From The South” in the May 24, 1862 edition, his name had been printed: Major General A. S. Johnston.

After details about the battle in a message from Jefferson Davis, these words appeared: “…it is but too true that Gen. Albert Sydney Johnston is no more. The tale of his death is simply narrated in a dispatch from Col. Wm. Preston, in the following words: ‘Gen. Johnston fell yesterday at 2 ½ o’clock, while leading a successful charge, turning the enemy’s right, and gaining a brilliant victory. A Minnie ball cut the artery of his leg, but he rode on until, from loss of blood, he fell exhausted, and died without pain in a few moments. His body has been intrusted to me by Gen. Beauregard, to be taken to New Orleans, and remain until instructions are received from his family.’” [i]

The successful charge and assurance of a painless death did little to ease the sorrow of Mrs. Johnston, a military wife and now war widow still living on the West Coast.

Eliza Griffin Johnston, born December 26, 1821, had survived adversity and hardship most of her life. Orphaned by age five, she lived with a grandmother and uncle during her youth. She probably knew or had heard of her cousin – Henrietta Preston – who married a young West Point graduate and officer, lived at Jefferson Barracks in Missouri, and had three children before her death from consumption in 1835. She likely heard her elders discussing the new Republic of Texas and opportunities in the West, but such family news and discussions probably did not make much impression of the young teenager who had a string of devoted beaux by age eighteen.

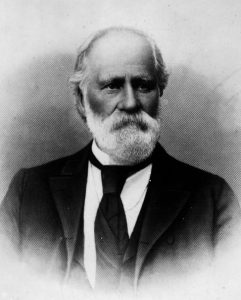

Talented and pretty, Miss Griffin had an exciting life in Louisville, Kentucky. The arrival of a former U.S. officer, now turned Texan planter, may not have interested her at first. (He was eighteen years older than her.) However, Albert S. Johnson persisted in his courtship and several years later Eliza married him on October 3, 1843, and moved to China Grove Plantation in Texas. Six children joined the Johnston family over the next years: Albert Jr., Hancock, Mary (died), Margaret, Griffin, and Eliza Alberta.

Three years later in 1846, the Mexican-American War broke out. Eliza did not want her husband to fight, but the couple eventually reached a compromise: he could join General Zachary Taylor, but promised not to enlist after six months of volunteer service. Johnston’s war experiences were brief and impactful. He helped train volunteers into disciplined soldiers, gained a positive reputation for courage and leadership, and served with Jefferson Davis. In October 1846, he kept his promise to Eliza and returned home, despite the tempting offer of a command position.

The home – China Grove Plantation – created economic hardships for the family. However, the property was more like a wilderness farm than a traditional, iconic plantation. After seasons of growing corn and cotton, the finances were in shambles, and the Johnston Family lost the plantation and owed $8,000. Albert insisted on repaying the debt and held the respect of his neighbors who understood the hardships of farming in that part of Texas.

While Albert struggled with the money problems, Eliza chased after their little ones and managed the household. She “held down the homestead” for the long weeks when Albert was away, fulfilling his new army position and serving as paymaster for the Army Department of Texas with the rank of major. However, the travel and constant absence from his family wearied Albert; in 1855, through the lobbying efforts of Jefferson Davis and Eliza, Albert transferred to command the 2nd U.S. Cavalry.

Though Eliza had initially disliked the idea of her husband in the military, she came to embrace the opportunities and stability that the military offered him, especially after the family’s financial difficulties. She made the journey from Missouri to Texas with the 2nd U.S. Cavalry, enduring a journey of 750 miles during the winter, in a wagon with her young children.

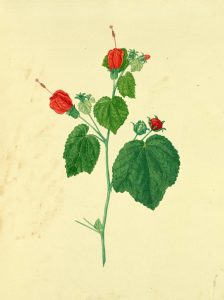

Eliza Johnston kept a detailed journal about her journey and other written records during her life. For the march to Texas, her writing provides valuable details about the military journey. She also enjoyed botany and in her spare time sketched and painted wildflowers in the Lone Star State. Her love of words and the arts brought culture to military outposts and left important sources for researchers.

When the 2nd Cavalry received orders to police Mormon violence in Utah, Eliza – at Albert Johnston’s insistence – took the family to live in Kentucky after he and others explained the increased dangers in that territory. News of Albert’s promotion to U.S. Brevet Brigadier General reached Eliza in 1858, and two years later, he returned to the family after being honorably relieved of command and given extended leave.

Then orders arrived for General Johnston to return to California as Commander of the Department of the Pacific. The army agreed that the family could travel to the new post. Eliza packed the trunks, and the family left New York City on December 21, 1860, traveled to the Isthmus of Panama, crossed, and sailed to San Francisco. Barely settled, news arrived of Texas’s secession, and General Johnston sent in his resignation while rumors swirled that he would hand over the Pacific Department to the Confederacy. His resignation was accepted on May 6, 1861, and Albert made preparations to leave.

In Los Angeles, Eliza waited, enduring her last pregnancy without the support of her husband. Outside the house, her newest hometown clamored with rumors and pro-Southern sympathies while Federal authorities scrambled to maintain presence and authority. Ultimately, the establishment of Camp Drum in 1862 kept Southern California in the Union and out of a true secession crisis.

Eliza’s baby – named Eliza Alberta – arrived on August 30, 1861. Happy family news and announcement of Confederate promotion crossed the continent. Albert Johnston received appointment to command the Confederate Military Department #2 on September 10, 1861 – defending a region that included Indian Territory, Kentucky, Missouri, Tennessee, Arkansas, and parts of Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana. Despite his duties and desperate scramble for troops, Albert wrote to Eliza in December 1861, saying: “You & the children occupy every thought not devoted to business… I was rejoiced to know that you & the dear little ones were all safe & well. I pray God that you have so continued since then.”[ii]

In his last known letter to the family in Los Angeles, General Johnston wrote: “The boys must go on in their studies and be encouraged to read history & other proper works of literature and as far as possible be prepared for the station they will be called on to fill when they are old enough to enter the arena of life… Kiss each boy & each girl. I shall love the youngest better if you give her your own name – May God bless you & them & preserve you free from all harm.”

Safe in California, far from the scenes of war, Eliza and the children waited, preserved from all harm, but about to be personally affected by the distant conflict. In April 1862, Johnston and his army moved from Corinth, Mississippi, and launched an attack near Pittsburg Landing (Shiloh), Tennessee. In the first day’s fighting, General Johnston led units forward and was wounded in the right leg. Thinking the wound was insignificant, he refused medical aid, then alarmed his staff officers when he fainted. They searched desperately for the wounded and spent valuable moments trying to revive him with liquor before realizing the wound in the leg had hit a major blood vessel. General Albert S. Johnston died on April 6, 1862, and was buried in New Orleans, but later reinterred in Austin, Texas.

Widowed, Eliza Johnston stayed in California. Her brother developed Rancho San Pasqual and much of East Los Angeles, and she had a home built on property purchased from him in what is modern-day Pasadena. By 1863, the finished house included nine rooms, and Mrs. Johnston called it “Fair Oaks.” She lived there only briefly, leaving the home in April 1863 after the death of her son, Albert S. Johnston, Jr. Tragically, the young man was among the twenty-six dead after the explosion of Phineas Banning’s steamship S.S. Ada Hancock in San Pedro Harbor.

She died in Los Angeles on September 25, 1896. Eliza is buried in Angelus Rosedale Cemetery in her final hometown, still thousands of miles from her husband who is buried in Austin, Texas. Part of her obituary pays tribute to her religious faith and influence in California: “Mrs. Johnston was a member of the Episcopal faith, and for years was prominent in that faith. She was of a singularly lovable character, and had many friends, not only in Los Angeles, but throughout the state, who will sincerely mourn her death.”[iii]

On his journey to the Confederacy, Albert S. Johnston had penned a letter to his wife, including these words: “We should not borrow trouble by apprehension of danger in the future, but nerve ourselves to meet them bravely should they come – I am happy that…I can discharge my duty in whatever position fortune may assign me, with equanimity & cheerfulness with the hope that there is much good in store for us… Can I better testify my love for you & my children than by this journey? Love & hope cheer me on to discharge a great duty which may in the end benefit you.”[iv]

Later, Eliza Griffin Johnston may have read those words and questioned them. His pursuit of duty had led to his death on the battlefield at Shiloh. However, as difficult as it was at the time, California was one of the safest places of Eliza and the children. Left behind, she survived the four year war in a place far different than Missouri, Kentucky, or Texas. A place that remained unscarred by actual battle and a place that offered security and the opportunity to raise her children, far from the scenes of war and reconstruction.

Ultimately, Eliza’s choices and life story from young bride and frontier homesteader to military wife, devoted mother, and brave widow, reflected her husband’s belief to “nerve ourselves to meet [danger] bravely.” A principle that he followed until his death and an ideal that she undoubtedly clung to when the tragic news arrived in California from a battleground in Tennessee.

Sources:

Roland, Charles Pierce. Albert Sidney Johnston, Soldier of Three Republics. (Austin, University of Texas Press, 1964).

[i] Los Angeles Star, May 24, 1862. First noted publication in the paper about the Battle of Shiloh and A.S.J.’s death.

[ii] Albert S. Johnston to Eliza Johnston, December 29, 1861.

[iii] Eliza Johnston Obituary, The Los Angeles Herald, Volume 25, Number 362, 26 September 1896.

[iv] Albert S. Johnston to Eliza Johnston, January 6, 1862.

Gorgeous post. I would like it but I am not able to do that when I am logged into ECW.

Well done. The rest of the story as Paul Harvey used to say. Love these posts about the wives and families of Civil War soldiers.l

Thanks, Larry! Sometimes, we can even learn about the guys’ military decisions when we understand their family life details.

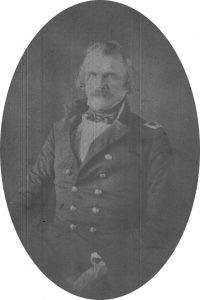

Very fine work. Please note the photograph of Albert Sidney Johnston you provide. This picture, now lost as far as I know, was taken in Salt Lake City in 1859 or 1860. Note how ASJ is casually resting his left (in the picture) hand on a sword. That is the pommel of the sword not his white sleeve exposed. That sword, a Model 1850 Staff and Field Officer of infantry sword was given to him by his staff shortly before the picture was taken. That sword is the sword he was wearing when KIA at Shiloh. As many of you know who have read Roland ASJ, in late 1860, was sent a full dress General Officer’s sword by friend F.J. Porter but that sword, possibly, did not reach Johnston before he left for California . Both swords are extant! God love y’all-Philip

Did you know that the widow of General Albert Sidney Johnston, Eliza Griffin Johnston, had absolutely no relics of of her husband’s Confederate Army service? What follows from my last reply is interesting research done in reference to Johnston’s Shiloh sword:

Brigadier General Albert Sidney Johnston, upon his return from Utah in 1860, was sent a regulation Model 1860 Staff and Officer’s sword by his admiring friend Major Fitz-John Porter ( Assistant Adjutant General). This style of sword, whose whereabouts in Maryland is known to this writer, was not typically used in the field until after the Civil War, and most often relegated for “full dress” or “walking out” occasions. It was a fine gift from his former Utah Chief of Staff. A last minute gift to Johnston before he departed for California it is not known if it was received at all by Johnston (documents on file)? Johnston, earlier while in Utah Territory, was presented a Model 1850 Staff and Field Officer’s sword by “members of his Utah staff”. A ca.1860 daguerreotype portrait of the man taken in Salt Lake City shows him in a brigadier’s uniform with this sword at his left hand. This picture, now lost I believe, was certainly taken late in 1859 or 1860 in Salt Lake City. It is our certainty that the sword in that picture was the sword Albert Sidney Johnston wore as his service saber when killed at Shiloh. It was subsequently worn by his son, Colonel William Preston Johnston ADC to Jefferson Davis. Please read what follows:

When General Johnston was mortally wounded, Colonel William Preston Johnston, his son by his first marriage, came to Corinth Mississippi on April 17th 1862 and claimed all his father’s equipment. The inventory of ASJ’s worldly goods, dated April 17th now resides at Tulane University. The only Shiloh campaign item WPJ intended to send to his step mother who was then living in Los Angeles, and this certainly proved impossible under wartime conditions, was a “Station Uniform” (sic) valued at $500; a fortune at that time! He gave his Uncle General William Preston the “pistol” his father wore and a “canteen”. Other than a blanket, which he gave Ran, Johnston’s freed slave and 2 horses (one sold to William Preston, the other Fire-eater send to Arkansas to recuperate) all the other things he carried with him immediately to Virginia. Among these was his father’s “1 sword” (sic). We believe strongly that William Preston Johnston wore his father’s sword as ADC to Jefferson Davis for the next three years. When William Preston Johnston was captured with the Jefferson Davis party in the “trappings his father used at Shiloh”…which were greatly prized by him.” were taken from him as trophies by members of the 4th Michigan Cavalry. This occurred May 10, 1865 (The Century Magazine 1883). Be aware that when his father, General Johnston, fled California in 1861 he carried very little with him; a horse a paid servant and an “ambulance” (sic). Most of his, ASJ’s, military trappings from a 35 year career he, out of necessity, left with his second wife in California Eliza Griffin Johnston. When he arrived in Richmond, he had only the basics. One has to believe a General of Infantry (see brevet of November 1857 not 1858 as some suppose.) would choose to wear a general foot officer’s sword since this was regulation for high ranking officers, general officers, when in the field! I refer you to the service swords of Lee and Jackson. These are virtually identical to ASJ’s sword. All the items subsequently donated to museums and family members by Mrs. Eliza Griffin Johnston before and after her death were the items Johnston LEFT in California in 1861. Relics of his previous service. One must conclude that the Shiloh sword was this regulation 1850 Staff and Field Officer’s sword presented to ASJ while in Utah Territory. Although Johnston had a distaste for the war against the Mormons he was never-the-less very proud of his long over due brevet to Brigadier General’s rank and this sword with the inscription: “Presented to Brigadier General Albert Sidney Johnston by members of Staff Utah Territory” followed by “1857” was a great honor to him (the date “1857” is the date of his brevet not the date the sword was presented, that date was certainly 1859 or 1860).

In conclusion, I direct you to the New Orleans Metairie Cemetery equestrian statue of Johnston designed in great detail by Alexander Doyle under William Preston Johnston’s personal supervision (correspondence at Tulane). On that statue Johnston is clearly not wearing a cavalry saber (his pre-1857 cavalry officer’s saber was donated by Eliza Griffin Johnston to a New Orleans Museum in memory of her drowned son and its whereabouts today is unknown in phone conversation with Prof. Roland 2012 I learned of this one), nor a Model 1860 Staff Officer and Field Officer’s sword, but a line officer’s or M1850 Staff and Field Officer’s sword; certainly this is a facsimile of the sword he got from his “Staff” just a few years earlier when in Utah. In fact, the exacting and renowned Civil War artist Don Troiani chose Doyle’s Metairie equestrian statue of Johnston as his model in his work “Men of Arkansas”. Here he wear the 1850 Staff and Field saber. Supporting documents on file. Thanks for indulging me and God love ya!