A “Melancholy Suicide”: The Death of Brigadier General Philip St. George Cocke

On December 26, 1861, Confederate Brigadier General Philip St. George Cocke’s wife, Sallie, reluctantly left her home that Thursday evening to attend a neighbor’s party. The general had not been well since returning home, suffering from a mental breakdown. He declined the invitation from his neighbor but encouraged his wife and family to go on without him. Sallie found her husband asleep in his bedroom and felt assured that it would not do any harm leaving him alone for a short time. It was a decision she would likely regret for the rest of her life.

The Cockes returned home an hour later, but the general was nowhere to be found. Sallie sounded the alarm and every room was searched. At last, they discovered the general’s lifeless body outside their mansion with a single gunshot wound to his temple and a crater in his skull where the bullet had exited. Next to him on the ground lay a revolver. The wealthy plantation owner, West Point graduate, and Confederate general was dead at the age of 53. Cocke has the inglorious reputation as being the only Confederate general to have committed suicide during the American Civil War.

Six months prior, Cocke was demoted from brigadier general to colonel after being transferred into the Provisional Confederate Army despite being one of the first officers to answer the call to defend Virginian soil. He watched as other men were promoted to generals ahead of him even though they had entered Confederate service after him. He lashed out by writing letters, even accusing Major General Robert E. Lee as being one of the main culprits for this affront. “I think General Lee has treated me very badly and I shall never forgive him for it,” Cocke complained to the superintendent at VMI, Francis H. Smith. Cocke did eventually receive a promotion to brigadier general in the Provisional Confederate Army four months after his demotion. By November 1861, rumors began to circulate among Cocke’s subordinates that he was suffering from a mental breakdown. He returned to his plantation in December and was dead before the New Year.

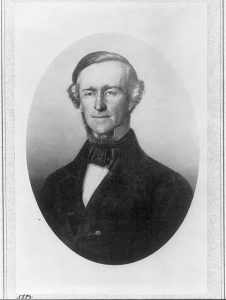

The son of the War of 1812 militia general, John Hartwell Cocke, Philip St. George Cocke graduated from the U.S. Military Academy in the Class of 1832 – ranked sixth among forty-five cadets. Upon graduation in July, he was commissioned a second lieutenant in the Second Regiment of Artillery. He resigned his commission two years later, married, and became one of the wealthiest slave owners and cotton producers in the South. He served as the president of the Virginia State Agricultural Society for a period of three years and frequently wrote about agricultural production. He even tried experimenting with Merino sheep by raising them on his plantation in hopes of introducing them to Virginia.

Despite a brief career in the army, Cocke saw the value of military education. He was a benefactor of the Virginia Military Institute (VMI) – established in November 1839 – and served on the board of visitors for nine years. He helped to establish an agricultural curriculum at VMI by donating $20,000. Two scholarships were also established through his generous donations, which were used as scholarships to cover room and board and tuition for two students. Cocke befriended Francis H. Smith, the superintendent of VMI, and endorsed his travel to Europe in 1858 to visit seminaries and institutions so that he could implement their systems of education at VMI. Four of his sons would go on to attend and graduate from the institution: John Bowdoin Cocke (1856), William Ruffin Coleman Cocke (1867), Giles Buckner Cooke (1859), and Philip St. George Cocke, Jr. (1866). VMI was a vital part of Cocke’s life as much as his plantation.

When Virginia seceded from the Union on April 17, 1861, Cocke offered his service to defend his native state. Three days later, Governor John Letcher appointed him a brigadier general on the same day Colonel Robert E. Lee resigned his commission in the U.S. Army. The governor gave Cocke supreme command of the state’s forces along the Potomac River. Cocke wrote to Superintendent Smith telling him that he when arrived to Alexandria the day after his appointment he showed up “with naked hands and in my plantation dress…”

From his headquarters at Culpeper Court House, he provided direction in the early weeks of the war, gathering scattered Confederate units to defend the state. He hired a draftsman to copy charts and to compile a map of the Potomac Department. He wrote to Major General Robert E. Lee – appointed to command Virginia’s forces on April 23 – asking him to send as “many educated and experienced officers” as he could spare to serve on his department’s staff. He also requested VMI graduates to serve as “drill-masters, brigade inspectors, and other wants in the various schools of instruction and practice…” By May 15, Cocke had collected about 1,000 men and two guns to form the core of a force to defend Virginia.

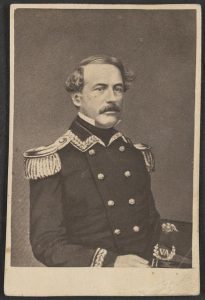

When Virginia’s forces were transferred to the Provisional Army of the Confederacy on June 8, Cocke was demoted to the rank of colonel. He viewed this as an insult and expressed his displeasure to General Lee on May 12. Lee wrote back to Cocke from Richmond the next day. “Recognizing as fully as I do your merit, patriotism & devotion to the state,” Lee declared, “I do not consider that either rank or position were necessary to bestow upon your honour, but believe that you will confer honour on the position. In the present crisis of affairs, I know that your own feelings, better than any words of mine, will point out the course for you to pursue to advance the cause in which you are engaged.” On May 21, Brigadier General Milledge L. Bonham, a congressman from South Carolina, superseded Cocke in command of the Potomac Department, further upsetting him. These rebuffs were more than the proud Virginian could stand.

Cocke watched as other politicians besides Bonham, like John B. Floyd and Henry A. Wise, were appointed to the rank of brigadier general during the months of May and June while he was passed over. “To think that Wise and Floyd being made Brigadiers at the same time that I am now reduced to a Colonel and ranked by every Colonel in the nominal army that has no real existence, viz: the ‘Provisional Army of Virginia,’” he wrote to Smith on June 15. “I should have been second in command at Manassas today, but some ‘Provisional Army’ Colonels rank, although I am the senior officer of the Virginia Volunteers now numbering thirty-five or forty thousand rank and file in the service, whilst there is not a single company of rank and file in the said Provisional Army and never will be. This is a beautiful system…”

Cocke wrote to Jefferson Davis on the same day as he penned this bitter letter to Smith. He pleaded his case to the Confederate president and took a shot at Lee and the other officers who had only recently resigned from the U.S. Army to join the Confederacy. “I was the first man called upon in the State and offered high and responsible military command by the Governor and Council…and was already in position in Alexandria before Gen’l Lee or any resigned officer of the U.S. Army had reached Richmond,” he wrote to Davis. “My academic and army record, date and rank placed me below but few that have entered up to this time in the service of the State, or can hereafter do so…I would scorn, sir, to seek to fill any position which I did not feel confident of the ability to fill…”

Despite his resentment, Cocke performed well in command of a brigade in Brigadier General Pierre G. T. Beauregard’s Army of the Potomac during the Battle of Bull Run on July 21, 1861. Brigadier General Joseph E. Johnston afterward reported that Cocke directed his brigade with “alacrity and effect” during the engagement. General Beauregard likewise made favorable mention of Cocke in his battle report. “Thanks are due to Brig.-Gens. Bonham and Ewell, and to Col. Cocke and the officers under them, for the ability shown in conducting and executing the retrograde movements on Bull Run,” Beauregard wrote, “movements on which hung the fortunes of this army.” Cocke did eventually receive the promotion he sought. He was elevated to brigadier general in the Provisional Army on October 21. (His commission was confirmed on December 13, 1861).

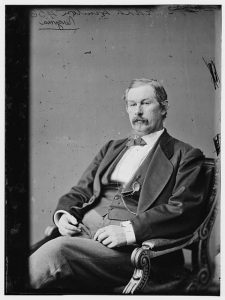

But all was not well with Cocke. The general’s subordinates noticed a disturbing change in his demeanor. Colonel Robert E. Withers, of the 18th Virginia Regiment, said the general seemed “distrait” further describing that “he was often abstracted and evidently oblivious of his surroundings, the expression of his eye was not normal and there was an indefinable something in his whole bearing…” Colonel Eppa Hunton, of the 8th Virginia Regiment, observed Cocke’s peculiar behavior when he was invited to dine with the general after his regiment was assigned to his brigade at the end of November. “While going to his tent he was in absolute silence for some distance, he struck his forehand two heavy blows, exclaiming, ‘My God! My God! My country!’ I was very much astonished, and felt that his mind was a little off…” Had the anger, stress, and anxiety caused by his demotion months prior led to a mental breakdown?

Cocke left his brigade apparently on sick leave in December and returned to his mansion and plantation, Belmead, about thirty miles west of Richmond. On January 3, 1862, a friend of the Cocke family, J.D. Powell, wrote to Colonel William N. Pendleton while he was on sick leave, speaking of the tragedy that had occurred there. “Poor Gen. Cocke since his return home has been in a state of alternate excitement and depression,” he declared in his letter to Pendleton. He informed Pendleton that Cocke had taken no interest in his home life or anything else since his return. The general slipped further into depression as he brooded over his inability to be with his brigade. He “would say he was unfit for any duty being only a burden to his family, his community, and himself.” The day of his death, Cocke penned his letter of resignation, overcome with anxiety, depression, and shame. While his family was away that night, he ended his life.

The Staunton Spectator provided a graphic description of Cocke’s death in a column titled “Melancholy Suicide.” While Powell said that the dejected general had shot himself in the temple, the paper declared he had shot himself in the mouth, and “the ball penetrated upwards, and went through the top of his skull producing instant death.” In either case, both wounds indicated a self-inflicted wound. “It is impossible to assign any cause for this rash act,” the paper stated. Colonel Withers was confident it was attributed to a mental breakdown. “I never heard any cause assigned for this rash act except mental aberration,” he reported. A VMI graduate and Confederate artillery officer, Captain Thomas Henry Carter, asked his wife for details about Cocke’s suicide when he wrote home. “I was greatly shocked to hear of Genl. Cocke’s suicide,” Carter declared. “It is said here that he has been suspected at times of slight insanity. Tell me the circumstances when you write.”

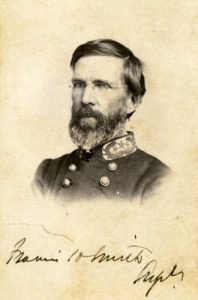

Superintendent Francis H. Smith paid tribute to his friend in his report to the adjutant-general of Virginia, William H. Richardson, on February 4, 1862:

It was my privilege to be associated with him on terms of the closest intimacy for the period of 32 years, and I can say of him, in truth, that I never knew a purer, more high-toned or unselfish gentleman. Truth is every noble impulse, his life and his fortune were alike tendered, in the hour of his country’s peril, upon the altar of his country’s service; and after a campaign of eight months in the face of enemy, and winning laurels on the plains of Manassas, as a brigade commander, he returned to his home, worn out by the protracted care and toil, to die.

The Reverend Cornelius Tyree gave an elegant sermon during Cocke’s funeral when he was buried on his plantation grounds two days after his death. “With a temperament nervous and excitable, being for more than a year under intense, high-wrought and continued mental anxiety about the country, and dwelling on the gloomy aspect of our revolution,” Tyree continued, “his bright intellect gave way and was wrapped in the somber cloud of irrationality, which caused his mournful end.” Tyree praised Cocke’s “skill and daring” during the Battle of Bull Run. “I do regard his death as truly and clearly a sacrifice for our country as if he had fallen on the 21st of July,” he declared. “Gen. Cocke was just as much a martyr for Southern liberty as Generals Bee or Bartow.”

Most concluded it was an unfortunate end for the eminent Virginian. Cocke’s time in a Confederate uniform was short-lived and he never really got much of a chance to show his mettle as a brigadier general. Tragically, his mental breakdown was to blame for the premature end to his military career and subsequent death.

Editor’s Note: If you know someone going through a difficult time or mental health struggles, we encourage you to seek help. One resource is the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline: 1-800-273-8255

Bibliography

“Beauregard’s Official Report.” In The Rebellion Record: A Diary of American Events, with Documents, Narratives, Illustrative Incidents, Poetry, Etc., 338-343. Edited by Frank Moore. Vol. 2. New York: G.P. Putnam, 1862.

Carter, Thomas H. A Gunner in Lee’s Army: The Civil War Letters of Thomas Henry Carter. Edited by Graham T. Dozier. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2014.

Cocke, Philip St. George. Philip St. George Cocke to Jefferson Davis, June 15, 1861. Letter. Virginia Military Institute Archives. Records of Superintendent Francis H. Smith, 1839-1889.

Couper, William. One Hundred Years at V.M.I. Vol. 2. Richmond, VA: Garrett & Massie, Inc., 1939.

“Gen. Johnston’s Report of the Battle of Manassas.” In The Land We Love. A Monthly Magazine Devoted to Literature, Military History, and Agriculture. November-April, 1866-67, 156-163. Vol. 2. Charlotte, NC: Published by Hill, Irwin & Co., 1866-67.

Hollywood Cemetery. “Philip St. George Cocke.” Accessed March 29, 2019. https://www.hollywoodcemetery.org/phillip-st-george-cocke.

Hunton, Eppa. Autobiography of Eppa Hunton. Richmond, VA: William Byrd Press, 1933.

Journal of the Congress of the Confederate States of America, 1861. Vol. 1. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1904.

Journal of the Senate of the Commonwealth of Virginia. Richmond: James E. Goode, Senate Printer, 1861.

Longacre, Edward G. The Early Morning of War: Bull Run, 1861. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2014.

Memorandum Relative to the General Officers Appointed by the President in the Armies of the Confederate States, 1861-65. Washington: The Military Secretary’s Office, War Department, 1905.

Memphis Daily Appeal (Tennessee), December 28, 1861.

Powell, J.D. J.D. Powell to William N. Pendleton, January 3, 1862. Letter. #1466. Southern Historical Collection, Louis Round Wilson Special Collections Library, University of North Carolina. The William N. Pendleton Papers, 1798-1889.

Special Report of the Superintendent of the Virginia Military Institute, on Scientific Education in Europe. Richmond, VA: Printed by Ritchie, Dunnavant, & Co., 1859.

Staunton Spectator (Virginia), December 31, 1861.

The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Series I, Volume II. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1880.

Tyree, Cornelius. The Benefits of Affliction. A Sermon on Occasion of the Death of General Philip St. George Cocke, Preached at His Late Residence, In Powhatan County, Va., on the 28th December, 1861. Richmond, VA: Macfarlane & Fergusson, Printers, 1862. https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/010944633.

Virginia Military Institute Official Register, 1907-1908. Winchester, VA: The Eddy Press Corp., 1908.

Welsh, Jack D. Medical Histories of Confederate Generals. Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 1995.

Wise, Jennings C. The Military History of the Virginia Military Institute from 1839 to 1865. Lynchburg, VA: J.P. Bell Co., Inc., 1915.

Withers, Robert E. Autobiography of an Octogenarian. Roanoke, VA: The Stone Printing & MFG. Co. Press, 1907.

Excellent post. I long wondered why Cocke killed himself. It still seems like something of a mystery, and I think his reduced rank was not the heart of the matter, particularly since he did get a promotion. Maybe he was overwhelmed by the war itself and what it entailed.

Excellent post. Thanks so much for sharing