Sink Before Surrender: The CSS Virginia Gets Underway

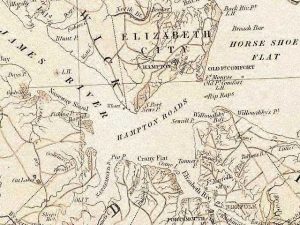

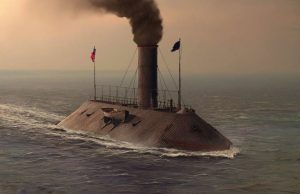

In the dawn of that fateful Saturday, March 8, 1862, the CSS Virginia lay alongside the Gosport Shipyard quay on the west bank of the Elizabeth River across from Norfolk, Virginia, and just upriver from Hampton Roads. The storm passed in the night leaving a cloudless morning, “calm and peaceful as a May day,” recalled Midshipman Hardin B. Littlepage. The water’s surface barely rippled in a soft breeze from the northeast.[1]

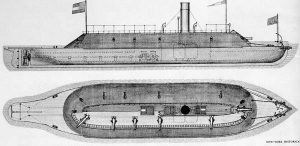

On this day, Virginia would destroy two major Union warships and damage others; on the next, she would engage the USS Monitor. Fifteen hundred men had labored for six months on the fearsome ironclad. She was a beehive of activity with mechanics and crew swarming to fit her for action. On the wooden hull of the former steam frigate USS Merrimack, a substantial casemate or armored shield had been constructed with a powerful battery of ten big guns. Under the prow was a cast iron, wedge-shape ram weighing 1,500 pounds.

Third Assistant Engineer Eugenius A. Jack thought Virginia looked like a sloping mansard house roof, but, “the black mouthed guns peeping from the ports gave altogether different impressions and awakened hopes that ere long she would be belching fire and death from those ports, to the enemy and crashing into their wooden vessels with that formidable ram sending them to the bottom.”[2]

According to her surgeon, Dinwiddie B. Phillips, Virginia “bore some resemblance to a huge terrapin with a large round chimney about the middle of its back.” She was not built for high winds or heavy seas and therefore could not operate outside the Virginia capes. “In fact she was designed from the first as a defense for the harbor of Norfolk, and for that alone.”[3]

Lieutenant Catesby ap R. Jones regarded the ironclad as incomplete as well as unseaworthy. There had been “many vexatious delays attending the fitting and equipment of the ship,” mostly from want of skilled labor and lack of tools and appliances.[4]

Virginia “was put up in the roughest way” wrote Confederate Army Captain William Norris. She “was in every respect ill-proportioned and top-heavy; and what with her immense length and wretched engines…was little more manageable than a timber-raft…. She steered very badly, and both her rudder and screw were wholly unprotected.” It would take thirty to forty minutes just to turn her around, “and she never should have been found more than three hours sail from a machine shop.”[5]

Virginia was badly ventilated, very uncomfortable, and very unhealthy, continued Lieutenant Jones. “The crew, 320 in number, were obtained with great difficulty,” mostly volunteers from various army regiments stationed about Norfolk, many of them Georgian. With fifty or sixty men in the hospital and others on the onboard sick list, the effective complement on this Saturday was about 250.[6]

“There was a sprinkling of old man-of-war’s men,” recalled Lieutenant John R. Eggleston, “whose value at the time could not be overestimated.” The rest “had never even seen a great gun like those they were soon to handle in a battle against the greatest of odds ever before successfully encountered.” Their first and only practice behind Virginia’s guns would be in battle.[7]

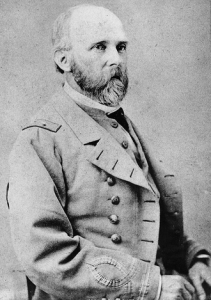

Two weeks earlier, Secretary of the Navy Stephen R. Mallory appointed Flag Officer Franklin Buchanan to command all Confederate vessels defending Hampton Roads. The CSS Virginia would be his flagship.

“Buchanan was a typical product of the old-time quarter deck, as indomitably courageous as Nelson, and as arbitrary,” recalled Lieutenant Eggleston. “I don’t think the junior officer or sailor ever lived with nerve sufficient to disobey an order given by the old man in person.”[8]

Mallory instructed Buchanan: “The Virginia is a novelty in naval construction, is untried, and her powers unknown, and the Department will not give specific orders as to her attack upon the enemy.” The secretary did, however, encourage him to test that ancient and fearsome weapon of Mediterranean rowing galleys—the ram—which now propelled by steam, had returned to action after three centuries. “Like the bayonet charge of infantry,” this mode of attack would compensate for scarcity of ammunition. It would be formidable even without guns.[9]

Mallory urged Buchanan to take advantage of the means and opportunity for a decided blow. “Our utmost exertions” are demanded. “Action—prompt and successful action” must follow. “I congratulate you upon it, and know that your judgment and gallantry will meet all just expectations.”[10]

The navy secretary had grand visions for this revolutionary new weapon. “Could you pass Old Point [Comfort] and make a dashing cruise on the Potomac as far as Washington, its effect upon the public mind would be important to the cause,” he posited in Buchanan’s orders. A subsequent letter of March 7 asked: “Can the Virginia steam to New York and attack and burn the city?”[11]

Presuming good weather and smooth seas, Mallory did not doubt Virginia could destroy the Brooklyn Navy Yard with its magazines, all the lower city, and much shipping. Bankers would withdraw their capital from the city. The enemy could never recover. Peace would inevitably follow. “Such an event would eclipse all the glories of the combats of the sea…. [and] would do more to achieve our immediate independence than would the results of many campaigns. Can the ship go there? Please give me your views.”[12]

Buchanan knew better, but he did have a plan. In late February, the flag officer met with Major General John B. Magruder, commander of the Army of the Peninsula, to arrange joint operations against Union Camp Butler and Newport News Point. Anchored there and blocking the James River leading to Richmond were the sailing warships USS Cumberland and USS Congress along with formidable land batteries within point blank range.

Buchanan knew better, but he did have a plan. In late February, the flag officer met with Major General John B. Magruder, commander of the Army of the Peninsula, to arrange joint operations against Union Camp Butler and Newport News Point. Anchored there and blocking the James River leading to Richmond were the sailing warships USS Cumberland and USS Congress along with formidable land batteries within point blank range.

Buchanan intended to sally forth in Virginia supported by five gunboats. “My plan is to destroy the Frigates first, if possible,” he wrote Magruder, “and then turn my attention to the battery on shore. I sincerely hope that acting together we may be successful in destroying many of the enemy.” General Magruder simultaneously would assault from landward.[13]

But on March 3, Magruder wrote to Buchanan: “It is too late to co-operate with my army in any manner with the Merrimac….” Muddy roads would not accommodate movement of his artillery; the enemy was heavily re-enforced at Newport News and Fort Monroe, and he heard that another 30,000 men would land before March 5th.[14]

Meanwhile, Magruder had been ordered to send at least 5,000 men and two batteries across the Roads to augment Major General Benjamin Huger in Norfolk. Intelligence reports indicated the enemy was preparing to swarm up the Dismal Swamp Canal from the North Carolina Sounds and attack the city from the rear. “We do not believe that you [Magruder] are in the slightest danger of an attack at present, either in front or by being outflanked by naval forces,” a conclusion with which Magruder disagreed.[15]

With apparent frustration, Magruder wrote Buchanan: “It would have been glorious” if Virginia had intercepted Yankee reinforcements as they were being landed from commercial transports. Now he was compelled to withdraw his little army back to a shorter line on the Warwick River. “Any dependence upon me, so far as Newport News is concerned, is at an end.”[16]

Magruder also believed that Virginia could make no impression on Newport News. Only concentrated fire from many ships would persuade enemy troops to evacuate the batteries while the mere presence of his meager force, “would incur a risk of disaster without any corresponding advantage.” Furthermore, Virginia could be injured by a chance shot at this critical time.[17]

But even if Virginia sinks all vessels at Newport News Point, it would do little good, Magruder opined. Better Virginia be stationed above the point as a floating battery to block Union gunboats from coming up the James and to anchor the Confederate army’s right flank on the river. Magruder’s fears would be realized just a few weeks later as McClellan’s mighty host descended on the Peninsula.[18]

Buchanan, however, was undaunted. He learned from a March 3rd edition of the New York Times that the USS Monitor passed her sea trials. She could be expected in Hampton Roads any day. He would get Virginia underway as soon as possible and do as much damage as possible before additional enemy reinforcements—land or water—arrived.

Ideally, Virginia would destroy or chase the wooden U.S. Navy out of the Roads, defend Norfolk and Gosport, disrupt the blockade, deny Union advances by water toward Richmond, and secure the south bank of the peninsula. This was not Washington or New York, but pretty good for one thrown-together warship and a handful of puny gunboats.

Buchanan hoisted his flag officer’s red pennant and commanded the squadron to get underway by 11:00 a.m. while unbeknownst to him, Monitor was indeed approaching Cape Henry at the mouth of Chesapeake Bay. All workmen, some making final adjustments to armor and machinery, were ordered off. The ironclad was cleared for action. Virginia cast off from the wharf. The last mechanics jumped ashore as she pulled away and stood downriver.

Buchanan hoisted his flag officer’s red pennant and commanded the squadron to get underway by 11:00 a.m. while unbeknownst to him, Monitor was indeed approaching Cape Henry at the mouth of Chesapeake Bay. All workmen, some making final adjustments to armor and machinery, were ordered off. The ironclad was cleared for action. Virginia cast off from the wharf. The last mechanics jumped ashore as she pulled away and stood downriver.

“The weather was fair, the wind light, and the tide half flood,” wrote Lieutenant Parker. Nearly every man, woman and child in Norfolk and Portsmouth gathered at Seawell’s Point, Craney Island, and other vantage points to observe the great naval combat. All shore batteries were manned. All work was suspended in public and private shipyards while those remaining behind thronged churches and offered prayers. Everything that would float from army tugboat to oysterman’s skiff was loaded to the water’s edge with spectators.[19]

“A great stillness came over the land,” continued Parker. Caps and handkerchiefs waved from river banks, “but no voice broke the silence of the scene; all hearts were too full for utterance; an attempt at cheering would have ended in tears, for all realized the fact that here was to be tried the great experiment of the ram and iron-clad in naval warfare.” Many thought Virginia would “sink with all hands enclosed in an iron-plated coffin” as soon as she rammed a vessel. Nevertheless, concluded Parker, those about to do battle went coolly about their duties.[20]

Buchanan intended to be in the Roads by 1:30 p.m. at full tide for optimum maneuverability in deeper channels. Final orders to his captains included a new signal consisting of the flag for the number one hoisted above the commodore’s pennant meaning “sink before you surrender.”

Excerpted from forthcoming book, With Mutual Fierceness: The Battles of Hampton Roads, by Dwight Hughes for the Emerging Civil War Series.

[1] Hardin B. Littlepage, “The Career of the Merrimac-Virginia: With Some Personal History,” in Mathless, Paul, ed., Voices of the Civil War: The Peninsula. (Alexandria, VA: Time-Life Books, 1997), 44.

[2] Eugenius A. Jack, quoted in John V. Quarstein, The CSS Virginia: Sink Before Surrender (Charleston, SC, The History Press, 2012), loc. 5251 of 12416, Kindle.

[3] Dinwiddie B. Phillips, “Notes on The Monitor-Merrimac Fight.” in Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, 4 vols. (New York, 1884-1888), vol. 1, 718.

[4] Catesby ap Roger Jones, “Services of the Virginia,” in Southern Historical Society Papers, 52 vols., vol. 11 (January-December 1904), 66.

[5] William Norris, “The Story of the Confederate States Ship ‘Virginia’ (Once Merrimac.) Her Victory Over the Monitor” in Southern Historical Society Papers, 52 vols., vol. 42 (September 1917), 205-206.

[6] Jones, “Services of the Virginia,” 66-67.

[7] Captain Eggleston, “Captain Eggleston’s Narrative of the Battle of the Merrimac,” in Southern Historical Society Papers, 52 vols., vol. 41 (September 1916), 168.

[8] Ibid.

[9] S.R. Mallory to Flag-Officer Franklin Buchanan, February 24, 1862, in Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion, 2 series, 29 vols. (Washington, D.C., 1894-1922), series 1, vol. 6, 776-777. Hereafter cited as ORN.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.; Mallory to Buchanan, March 7, 1862, in ORN, series 1, vol. 6, 780-781.

[12] Mallory to Buchanan, March 7, 1862, ORN, series 1, vol. 6, 780-781.

[13] Franklin Buchanan to J. Bankhead Magruder, March 2, 1862, in Quarstein, The CSS Virginia, loc. 1659-1660 of 12416, Kindle.

[14] J. Bankhead Magruder to Captain Buchanan, C. S. N., March 3, 1862, in The War of The Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, 128 vols. (Washington, DC, 1880-1901), series 1, vol. 9, 50. Hereafter cited as OR. All references are to series 1.

[15] J. P. Benjamin to J. B. Magruder, March 4, 1862, OR, vol. 9, 53.

[16] Magruder to Buchanan, March 3, 1862, OR, vol. 9, 51.

[17] J. Bankhead Magruder to General S. Cooper, March 6, 1862, OR, vol. 9, 57.

[18] J. Bankhead Magruder to General S. Cooper, February 24, 1862, OR, vol. 9, 44.

[19] PCaptain William Harwar Parker, Naval Officer: My Services in the U.S. and Confederate Navies 1841-1865 (Big Byte Books, 2014), loc. 3762 to 3776 of 5575, Kindle.

[20] Ibid.

Excellent re-telling of a story that we all thought we knew.

Cheers!