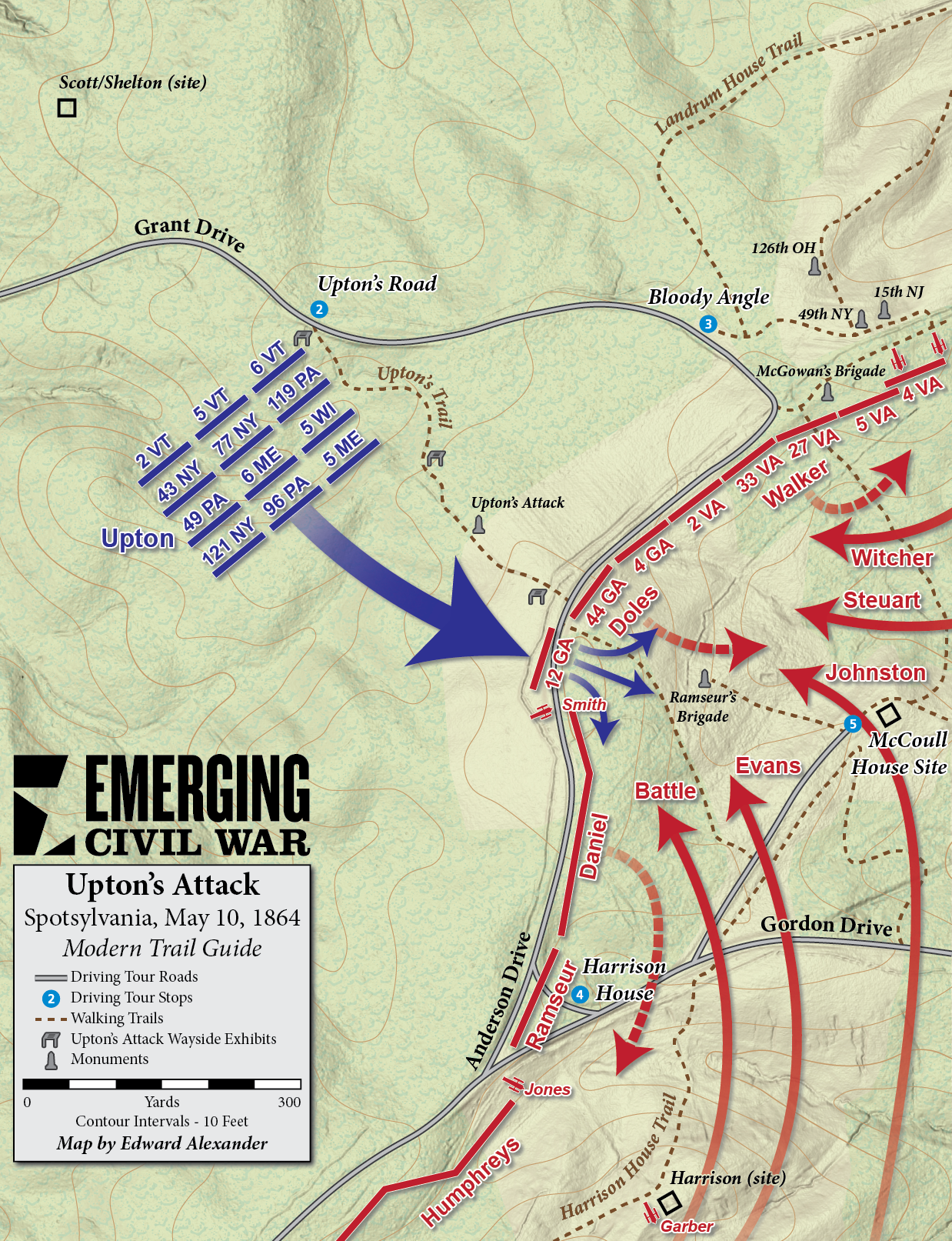

Upton’s Attack at Spotsylvania: Modern Trail Map

I can safely speak for the Virginia cabal of Emerging Civil War that we are big fans of Emory Upton. An influential military tactician, he is probably best known for his assault on the western face of the mule shoe salient at Spotsylvania on May 10, 1864. It is only appropriate that we introduce another original trail map on the 155th anniversary of that charge.

I can safely speak for the Virginia cabal of Emerging Civil War that we are big fans of Emory Upton. An influential military tactician, he is probably best known for his assault on the western face of the mule shoe salient at Spotsylvania on May 10, 1864. It is only appropriate that we introduce another original trail map on the 155th anniversary of that charge.

This portion of the battlefield is entirely preserved by Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park. Visitors looking to walk Upton’s assault should first orient themselves at the stop one along the Spotsylvania driving tour. The exhibit shelter is located near a monument marking the death site of Major General John Sedgwick, Sixth Corps commander, on May 9, 1864. One day later, Upton arranged twelve regiments from that organization in a tight column he believed could smash through the entrenched Confederate lines.

To follow that attack, drive to stop two, where parking is available, and then follow the designated trail. The path is parallel to the wartime road used by the Federals in aligning themselves for the assault. Several wayside exhibits along the trail fill in the details of the charge. A modern monument is located at the edge of the treeline. It stands about the average height of a soldier, a useful interpretive tool from Doles’s Salient up ahead, where the Confederate earthworks are still well preserved. Three hundred yards northeast, up the Park Service road from the salient, is the Bloody Angle, where Ulysses S. Grant attempted a larger version of Upton’s attack on May 12th. Neither attack accomplished its entire purpose, but they proved–for better or for worse–that entrenched Confederate defenses were not entirely impregnable.

Additional information about Upton’s attack can be found in a two part series by Dan Davis posted on this blog (Part 1, Part 2) and a visual tour offered by the National Park Service.

Thanks for posting this. Upton’s true innovation in this attack was not necessarily the formation, but the assignment of specific tasks to each line of three regiments to exploit a breakthrough. In September 1864, on the eve of the Third Battle of Winchester, he was already experimenting with the small formation tactics that became a core of his 1867 revisions. Truly an important and under-appreciated figure in the history of our military.

That’s an important distinction too. It’s not about getting to the primary objective. It’s about following it up and being able to keep the momentum going as you move on to the next objective. That, and having support, which Upton didn’t, to at least maintain your position once you’re there. Many failed Civil War frontal attacks did breach the enemy line, but it’s about what you do next.

Great map. Do you have a listing of available maps like this one. There is a monument to the 121st NY at Gettysburg with a bust of Upton on Little Round Top.

Haven’t done the best job with consist tagging, but maps like this are scattered throughout my posts. Some are also posted on makemeamapllc.com.