General Hartsuff’s Nine Lives

With a bullet wound to his left arm and a ball lodged in his chest, 25-year-old Lieutenant George L. Hartsuff submerged himself in a pond of brackish water hoping to evade detection. He did everything in his power to keep his large frame concealed for three agonizing hours as dozens of Seminole Indians searched for him. When he spotted alligators floating close by, he pulled himself out of the pond and staggered about 200 yards before collapsing among some palmetto bushes.

At nightfall, the injured lieutenant staggered in what he believed was the direction of Fort Myers. Besides enduring dehydration, hunger, and pain from his two wounds, Hartsuff suffered most from a hole in his boot causing pointed grass to poke through and tear at his flesh like razor blades. After two days of stumbling through Florida’s wetlands, Hartsuff tore a sheet of paper out of his pocketbook and wrote his name and a brief account of what had happened by using the blood from his wounds as ink. He pinned the bloody scrap of paper to his pant leg, and sensing the end was near, prepared to die.

“Hartsuff was one of the strongest, bravest, finest soldiers I ever knew, and one of my most intimate friends,” Major General John McAllister Schofield declared of the resilient officer two decades after his death. “[B]ut, unlike myself,” Schofield arrogantly confessed, “he was always in bad luck.” George L. Hartsuff may have experienced an uncomfortable number of run-ins with death throughout his life, but he seemed to find a way to escape these predicaments. Looking back on his life, another friend, Brigadier General James Barnet Fry, claimed that Hartsuff came from the rare class of men who seemed to live a charmed life and always somehow managed “to baffle even death itself.”

George Lucas Hartsuff was born on May 28, 1830, in the town of Tyre, New York. His father, Joseph Lucas Hartsuff, purchased a 120-acre farm when he was only 12 and relocated the family to Michigan. George spent the next six years laboring on the farm. The teenager’s life abruptly changed when Senator Kinsley S. Bingham secured for him an appointment to West Point in the spring of 1848. Four years later, Hartsuff graduated near the middle of the Class of 1852.

After finishing his studies at West Point, Hartsuff was appointed a second lieutenant in the Fourth Artillery and spent a year on the Texas frontier, where he came down with yellow fever and nearly succumbed to the deadly disease. It took him five months to regain his strength, but in December of 1853, he received orders to join the Second Artillery stationed in Florida.

On December 7, 1855, Hartsuff left the garrison at Fort Myers on a routine surveying mission. Eight soldiers and two teamsters, directing two wagons, made up Hartsuff’s party wading through the impenetrable Big Cypress Swamp. Thirteen days later, as the men rose at daybreak in preparation to return to the fort, forty Seminole Indians surrounded their camp and launched an assault. Three of Hartsuff’s men managed to escape the trap because they were away saddling their horses.

Hartsuff and the remainder took cover behind the wagons to meet the Seminole onslaught. During the exchange of gunfire from behind this makeshift barricade, a musket ball passed through Hartsuff’s left arm and lodged into his breast. With only one good arm, Hartsuff had a soldier load and hand muskets to him so that he could continue to fire. When the defenders ran out of ammunition, the young lieutenant ordered his men to scatter and escape as best they could to Fort Meyers.

Two days after escaping the Seminole ambush, as he lay dying, Hartsuff heard a familiar and welcoming noise. “I thought I was gone, when I heard the distant and indistinct roll of a drum,” he recalled. “My pistol had got wet in the pond, so I took it from my belt, unloaded it as best I could in my weak condition with my unhurt hand, and allowed the charge of powder to dry in the hot sun. Reloading, I waited until I heard the drum again, this time nearer, and when it stopped, fired off my pistol.” Then he fainted. When Hartsuff came to, he was surrounded by a crowd of astonished soldiers glaring down at him. Major Lewis Golding Arnold’s infantry company had been sent out to rescue the survivors and stumbled across the badly wounded lieutenant.

Surgeons tried to extract the bullet lodged in Hartsuff’s chest, but it was too deep. It would remain in his chest for the rest of his life. By early 1856, Hartsuff recovered from his wounds and returned to duty. He spent three years at West Point as an Assistant Instructor of Artillery Tactics, but he requested to rejoin his company stationed at Fort Mackinac, Michigan, erected on the island of the same name.

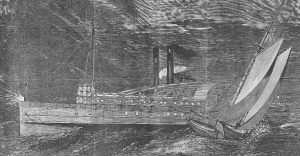

On September 7, 1860, Hartsuff left Chicago aboard the steamer Lady Elgin, on its return voyage to Milwaukee, Wisconsin, after placing an order for provisions for the garrison. Around 2:00 a.m., Hartsuff heard a disturbing noise outside his cabin. The Lady Elgin had collided with a 350-ton schooner, the Augusta, during a storm that night. The schooner’s bow penetrated the Lady Elgin’s hull causing it to sink. The captain of the Lady Elgin, Jack Wilson, directed Hartsuff to start passing out wooden life preservers to the passengers when it became clear that they would have to abandon ship.

Hartsuff was one of the last to evacuate the sinking steamer as it disappeared into Lake Michigan. He dove into the frigid water clutching a six-foot-long plank to use as a floatation device. Flashes of lightning revealed hundreds of other passengers struggling in the water, clinging to any debris they could grab hold of. Hartsuff drifted on his plank until sunrise, preventing hyperthermia from setting in by keeping his body and limbs continually in motion.

He paddled toward a larger fragment of wood and crawled onto it, joining four other male passengers huddled together. The professional soldier assumed a leadership role over the survivors, giving them specific orders to sit on the corners of the makeshift craft to keep it from capsizing. All appeared well as it drifted toward the Illinois coast until it was sideswiped by a whitecap causing the raft to overturn. Hartsuff managed to grab hold of a plank floating nearby and was washed ashore.

He had been in the water for ten hours and was hardly able to move when residents from Winnetka, Illinois, came to his rescue. “When I reached the shore, every attention which heartfelt sympathy could suggest was shown to me and the other survivors,” Hartsuff recalled of his rescuers. “One gentleman generously pulled off his coat and gave it to me, and another his boots.” Over 300 passengers perished in the catastrophe, including a fellow West Point alumnus, 44-year-old Garrett Barry, making it one of the greatest maritime disasters in the history of the Great Lakes.

By the time the Civil War commenced, 30-year-old Hartsuff had experienced a fair share of near-death experiences. The war would only add to these. Almost exactly one month before President Abraham Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers, he promoted Hartsuff to the rank of captain and assistant adjutant general. In August, Hartsuff joined the staff of the Brigadier General William S. Rosecrans, in command of the Department of West Virginia. Impressed with the young officer, Rosecrans recommended him for promotion. On April 15, 1862, Hartsuff was promoted to brigadier general.

One month later, he took command of a brigade in Brigadier General James B. Ricketts’ Second Division during the Northern Virginia Campaign until a severe illness forced him to relinquish command. His corps commander, Major General Irvin McDowell, reported that Hartsuff’s brigade surgeon personally called on him, expressing his concern for the general’s declining health. “I had frequent occasion to see him, speak to him [Hartsuff], and knew him to be suffering from illness which kept him a large part of the time on his back, which would have broken down any ordinary constitution,” McDowell declared. Hartsuff refused to be excused from duty even though he was relegated to a wagon and unable to keep any food down. The medical officer assured McDowell that Hartsuff would die if he continued in this condition. The corps commander intervened and temporarily relieved the stubborn Hartsuff of his brigade on August 22. This absence forced Hartsuff to miss the Battle of Second Bull Run.

Hartsuff was back in the command of his brigade for the Battle of Antietam in September. During the bloody engagement, he was shot in the hip Confederate sharpshooter as his brigade emerged from the northern part of East Woods on the morning of September 17. He tried to remain in the saddle among his troops, but as blood poured from his wound he grew faint and had to turn over command. Two soldiers supported him as far as he could walk as he made his way toward the rear until he had to be laid down on a blanket and carried the rest of the way. At the field hospital, not far from where Major Joseph K. F. Mansfield lay dying, a surgeon burrowed into the flesh of his hip in search of the bullet believed to be lodged somewhere near his pelvis. The doctor was unable to locate it, and deciding he was doing more harm than good, decided someone else more experienced should try to extract the bullet.

Once the desperately wounded general reached Middletown, five surgeons continued to prod for the ball but were unable to locate it. The general was taken to Frederick, Maryland, where, for a third time, a surgeon tried to dig out the bullet without success. On October 4, on his way back to Washington, D.C., after visiting Major General George B. McClellan, President Lincoln briefly stopped by and paid a visit to the severely wounded general resting at the home of Mrs. Ellen Ramsey. Despite initial concerns that he may not live, Hartsuff recovered from the fearful wound.

Hartsuff was subsequently promoted to major general on November 29, 1862, but he was still not well enough to return to his command. By April 1863, he requested to return to the field and was placed in charge of the newly organized XXIII Corps in Major General Ambrose E. Burnside’s Department of Ohio. The wound had not completely closed and it led to complications. “The severity of the exercise over the mountains and into and out of Tennessee dislodged the ball,” Hartsuff recalled of the Antietam bullet surgeons were unable to extract. It caused his hip and leg to go numb, and he was eventually unable to even mount a horse, forcing him to relinquish command. He remained in administrative duties for many months, eager for a chance to return to the front.

On March 12, 1864, Hartsuff experienced another near-death experience at the unlikeliest of places. While staying at his family’s farm, he heard the cries of his 48-year-old mother, Phebe, coming from outside. He found her neck deep in sewage and drowning. She had fallen through the decaying floor of the outhouse and was trapped in the drain. George rushed to her aid, plunging into the liquid waste after her. He supported her as she grew faint until rescuers arrived with ropes and dragged them both out.

During his mother’s rescue, Hartsuff sliced his leg from the ankle to the knee to the bone on a rusty scythe-blade masked in the excrement. He quickly wrapped his leg with a makeshift tourniquet to restrict the bleeding until a surgeon could arrive to stitch him up. This quick thinking saved his life. He lacerated his foot and sustained a nasty bacterial infection but managed to survive the bizarre ordeal.

On June 18, 1864, nearly two years after being wounded at Antietam, Hartsuff was ready to return to duty and asked the Retiring Board to grant his request. “I have the honor to request permission to proceed to the Army of the Potomac for the purpose of witnessing the operations now taking place there, as I am unwilling voluntarily to lose the experience I might gain thereby,” wrote Hartsuff. “I might besides make myself of service as Aid-de-camp to General Grant or some other useful capacity, which I would be very willing to do.”

Hartsuff reported to Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant during the spring of 1865. The Union commander-in-chief obviously thought that Hartsuff was worth keeping around, and telegraphed Major General George G. Meade, in command of the Army of the Potomac, on March 15, asking if he had a spot for him in the 9th Corps. While Meade liked Hartsuff, he responded to Grant the following day telling him that he currently had more officers to command divisions than divisions. “Under the circumstances,” Meade explained, “although there is no officer I should be more glad to have than General Hartsuff, yet I can not, in justice to others, say I want him.” Grant eventually found a position for the general and assigned him to the command of the Defenses of Bermuda Hundred four days after Meade declined his service. Hartsuff remained in Grant’s sphere of influence for the rest of the war.

Hartsuff stayed in the army after the war until his wounds forced him into retirement in June 1871. While visiting New York City in May 1874, he grew faint while playing a game of billiards at the Union League Club. While he was bedridden at the Sturtevant House Hotel, doctors determined that he was suffering from pneumonia. The infection apparently surfaced around the scar tissue and ball of his old Seminole War. Hartsuff survived yellow fever, a shipwreck, a scythe injury, and two gunshot wounds, but he was unable to shake the infection. On May 16, 1874, the general passed away at the age of 44, closing a remarkable saga of close calls, endurance, and survival.

Bibliography

Adee, David G. “Major General George L. Hartsuff.” In The United Service: A Monthly Review of Military and Naval Affairs, 62-75. Vol. 5. Philadelphia, PA: L.R. Hamersly and Co., 1881.

Boyer, Dwight. True Tales of the Great Lakes. New York: Dodd, Mead & Co., 1977.

Clark, Dwight F. “The Wreck of the Lady Elgin.” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society 39, no. 4 (December 1946): 407-418.

Clearfield Republican (Pennsylvania), May 27, 1874.

Cox, Jacob D. Military Reminiscence of the Civil War. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1900.

Cullum, George W. Biographical Register of the Officers and Graduates of the U. S. Military Academy at West Point N.Y., From Its Establishment, in 1802, to 1890. Vol. 2. 3rd ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, & Co., 1891.

Dempsey, Jack and Brian J. Egen. Michigan at Antietam: The Wolverine State’s Sacrifice on America’s Bloodiest Day. Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2015.

Edmonds, Sarah E.E. Nurse and Spy: Thrilling Story of the Adventures of A Woman Who Served As A Union Soldier. Washington, D.C.: The National Tribune, 1900.

Fry, James B. Army Sacrifices, or Briefs from Official Pigeon Holes. New York: D. Van Nostrand, 1879.

History of Livingston Co., Michigan: Illustrations and Biographical Sketches of Its Prominent Men and Pioneers. Philadelphia: Everts & Abbott, 1880.

In Memoriam, Maj. Gen. George L. Hartsuff, Class of 1852: Died May 16th, 1874, in New York City, Aged 44 Years. Norwood, MA: Press of Charles G. Wheelock, 1875.

Krick, Robert K. Stonewall Jackson at Cedar Mountain. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1990.

New Orleans Republican (Louisiana), May 19, 1874.

New Orleans Republican (Louisiana), May 22, 1874.

New Orleans Republican (Louisiana), May 27, 1874.

Schofield, John M. Forty-Six Years in the Army. New York: Century Co., 1897.

Seley Jr., Ray B. “Lieutenant Hartsuff and the Banana Plants.” Tequesta 23 (1963): 3-14.

Simon, John Y, ed. The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant: February 21-April 30, 1865. Carbondale, Southern Illinois University Press, 1985.

The Centennial of the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York, 1802-1902. Vol. 1. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1904.

Welsh, Jack D. Medical Histories of Union Generals. Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 1996.

I found myself amazed at the resilience of this man only to see he died at age 44. Quite a story and thanks for sharing.

Outstanding tribute. I always thought he was underrated.

Thanks! Hartsuff lived quite a remarkable life. I’m just happy that I could share his tale!

Hello, my name is Alan Renz and I am told that I am direct descendant of George Lucas Hartsuff. I would be very grateful for any opportunity to speak to you regarding his life. I know that this thread is older but have seen your remarks on newer articles and threads. Please let me know if speaking with you would be possible.

Alan, we are related. Mabel Hartsuff Trowbridge was my great grandmother. I spent summers on the Fenton, Michigan farm of her daughter, my grandmother, Florence Trowbridge Shaffer. As you likely know, Mabel Hartsuff married into what became, for a time, the extremely wealthy estate of Luther Trowbridge-an attorney and real estate speculator until he lost most of his net worth in the depression. My grandmother grew up in their 26 room Grosse Pointe Farms estate outside Detroit, and spent summers at the “cottage” at Point Au Barques, Michigan (a three story home on the tip of the thumb in Michigan). Florence Trowbridge initially married West Point graduate Colonel Cecil Winfield Land, and later Edward Shaffer. My mother, Barbara Land Green, gave birth to me in 1960, and I became a world class athlete in nTrack and Field, national record holder and Olympic Games finalist in the 1980’s: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bill_Green_(hammer_thrower) You can contact me at Bill Green

The 120 acre farm I believe was located in St. Clair County, Greenwood Twp. At the location of Hartsuff, MI. Corner of Wilkes and Brown Rds. A U.S. Post Office was established there until the towns demise. I heard he had a Brother who also made the rank of General and i am still trying to confirm that information.