E.P. Alexander’s Research Methodology

Every Civil War scholar should be familiar with the writings of Confederate First Corps artillerist Edward Porter Alexander (no relation). Many know him through Gary Gallagher’s compilation of his papers from the Southern Historical Collection at the University of North Carolina, published as Fighting for the Confederacy by UNC Press in 1989. Nearly as familiar, too, is Alexander’s own publication, Military Memoirs of a Confederate: A Critical Narrative (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1907), which trends more toward the subtitle than offering itself as a reminiscence. Alexander’s writing offers one of the best insights of the Army of Northern Virginia. His research began with an attempt to write a history of his corps. Frustrated by a lack of assistance, he abandoned that project. If completed, it would have provided the information that every battlefield historian desires.

Every Civil War scholar should be familiar with the writings of Confederate First Corps artillerist Edward Porter Alexander (no relation). Many know him through Gary Gallagher’s compilation of his papers from the Southern Historical Collection at the University of North Carolina, published as Fighting for the Confederacy by UNC Press in 1989. Nearly as familiar, too, is Alexander’s own publication, Military Memoirs of a Confederate: A Critical Narrative (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1907), which trends more toward the subtitle than offering itself as a reminiscence. Alexander’s writing offers one of the best insights of the Army of Northern Virginia. His research began with an attempt to write a history of his corps. Frustrated by a lack of assistance, he abandoned that project. If completed, it would have provided the information that every battlefield historian desires.

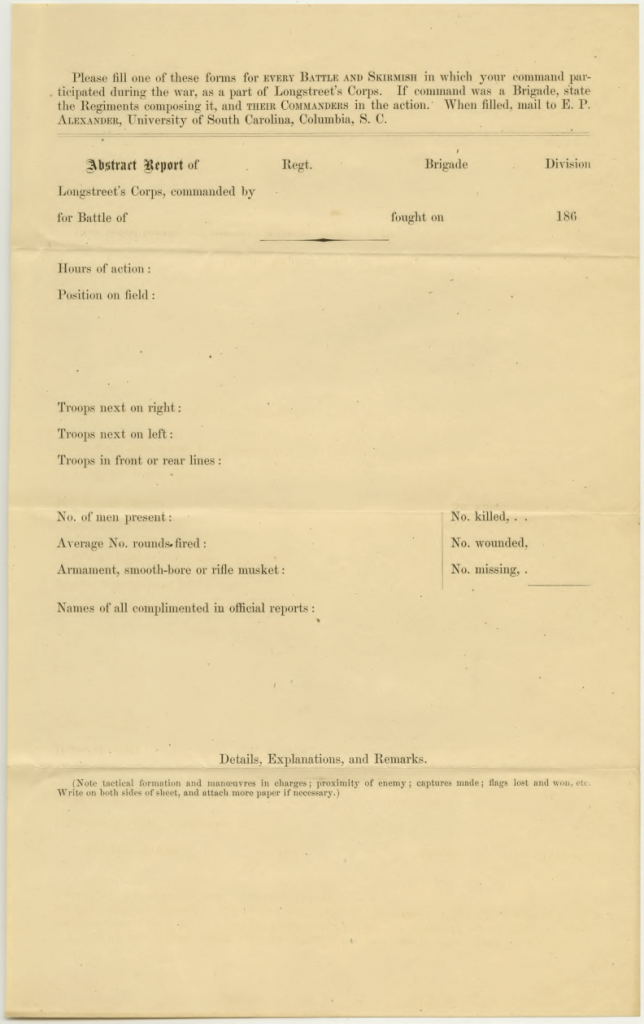

Shortly after the war, First Corps commander James Longstreet asked Alexander to write a history of the corps. Alexander optimistically expected to complete the project during his first three-month vacation as professor of mathematics and engineering at the University of South Carolina, but he soon realized he could not complete it without help. In the fall of 1866 he sent out a letter to every First Corps division, brigade, regiment, and battery commander and staff officer whose address he could track down. He requested copies of reports, primary accounts of prominent events written for publication or private reference, particular accounts of skirmishers not mentioned in general reports, topographical sketches of battlefields, unit histories, and orders of battle for each stage of the war. He also provided a form for each officer to input much of the data.

I found a blank copy of the desired abstract report in the Henry Lewis Benning papers at Columbus State University. Alexander hoped to gather information for where and when each regiment was located on every battlefield, who was around them, how many men were present, how much they fired and with what, the casualties taken, what official commendations were made, the tactics and maneuvers employed, and of course room for elaboration.

It was a noble attempt but an impossible one. The overall response rate was poor, as was the quality. Two years after beginning the project, Alexander confessed to Thomas Jefferson Goree, a former aide on James Longstreet’s staff, that he feared it was “foolishly undertaken.” He admitted:

I have worked at it now two vacations & all the leisure I could possibly steal from my duties day by day for nearly two years & I have hardly made a beginning.

What I want is not the general facts that everybody knows but the details & they only exist in the memories of survivors & I have to elicit them by correspondence & you cannot imagine how utterly hopeless a task this seems. For every one hundred letters and circulars I send, I get about ten replies, & of these ten, about six simply say that they have lost all records & can’t remember anything they think important enough to write. About three promised to write something they remember “as soon as they get time” & about one sends me what I want to get or ought to get from him. (Alexander to Goree, April 24, 1868, Thomas W. Cutrer, ed., Longstreet’s Aide: The Civil War Letters of Major Thomas J. Goree, Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1995, 156).

Benning, a brigade commander, was one who did reply, but Alexander complained that even Longstreet, who begged him to undertake the project, provided an unsatisfactory response. We should not blame the First Corps officers too much. The level of detail desired by Alexander was far too unrealistic. A century and a half later, most Civil War battlefield sites would struggle greatly to produce a similar report for each brigade, let alone regiment.

Personally, I have played around with different ways to compile the battlefield research material I collect, so I appreciate seeing the kind of information one of the Civil War’s foremost soldier-scholars thought was important to know.

This is a terrific post…what a great discovery finding that form…I also read the Gallagher’ work on E.P…you’re right, it’s terrific…many thanks.

What happened with the few replies that he did receive which had useful information? The would make for an interesting read.

I have not found any actual filled out forms. There are some narrative responses in the Alexander papers at UNC. Perhaps some more manuscripts, like Benning’s, with the papers of other commanders in various archives.

Great post. Thanks.

Great stuff!

Sometimes I feel his pain when I’m researching…………

I’m waiting to see a response to EPA along the lines of “I don’t have time to write, I’ll just tell you next time I see you” – like half of letters written home after a battle

When my division deployed for DESERT SHIELD and DESERT STORM, a detachment accompanied us whose primary duty was to record the history of the operation. Perhaps the modern Army has learned the lesson Alexander learned the hard way: record history as it occurs, while it’s still fresh in everyone’s mind.

For the sake of posterity it perhaps wasn’t the best idea to expect every CW officer to start from a blank piece of paper and produce a narrative report. I think an outline like EPA’s would have led to better reports in the ORs. I’m sure the modern military has some sort of outline better than “write a chronological sequence of what you remember happening.”

Why is this site not named, “The Emerging War Between The States”?