Thornsbury Bailey Brown – The First Casualty of Enemy Fire

First.

Last.

Only.

These words add tremendous weight when attached to a person or event associated with the Civil War. The absolute enormity of the war makes it hard to fathom there being a ‘first,’ a ‘last,’ or an ‘only,’ and needless to say there’s always room for debate…

Admittedly I’ve always been fascinated with these stories, particularly as they relate to casualties. Who was the first casualty of the Civil War? I suppose it depends on how we want to split those hairs. You had two soldiers killed by the accidental explosion of a cannon during the surrender ceremony at Fort Sumter on April 14, 1861. Four Massachusetts soldiers lost their lives during the Baltimore Riots five days later. Elmer Ellsworth of the famed ‘Fire Zouaves’ was killed by a hotelier in Alexandria, Virginia after removing a Confederate flag on May 24, 1861. But what of the first soldier on one side killed by a soldier from the other?

Allow me to introduce the terrifically-named Thornsbury Bailey Brown – the first soldier enlisted for the Union to be killed by a soldier enlisted for the Confederacy. Brown was killed at Fetterman, (West) Virginia 158 years ago today – May 22, 1861…two days before Colonel Ellsworth (sorry, Meg!).

Brown was 32 years old when he enlisted on May 15, 1861 as a Private in the Grafton Guards – a company of Union recruits organizing at Grafton – and was later recalled as a “leading spirit in forming the company.”[i] Grafton was an important junction on the Baltimore & Ohio line in northwestern Virginia with a large contingent of decidedly pro-Union Irish railroad workers, so much so that Colonel George A. Porterfield – sent there from Richmond to recruit Virginia state troops – was quickly run out of town. Porterfield would establish his point of rendezvous at Fetterman, just two miles south of Grafton on the old Northwestern Turnpike. It was there on May 13, 1861 that he would enlist Daniel W.S. Knight in the Letcher Guards, a company of Virginia recruits organized at Fetterman.

On May 22 Brown, in company with Daniel Wilson, a lieutenant in the Grafton Guards, traveled to nearby Pruntytown, Virginia to determine Union sentiment in the area and perhaps enlist willing men. Brown and Wilson took an indirect route to Pruntytown, careful to avoid the more than 100 Virginia troops encamped along the more direct route via Fetterman. Emboldened by either patriotism (or perhaps alcohol), Brown and Wilson opted for a return trip via the Northwestern Turnpike.

It was 9pm when the pair approached Fetterman Crossing, where a bridge across the Tygart Valley River intersected with the Baltimore & Ohio rail line. There they encountered Daniel Knight and two companions of the Letcher Guards on picket duty at the crossing. There are varying accounts of what happened next…

Knight and his companions called on Brown and Wilson several times to halt. Brown demurred, exclaiming Damn him, what right has he to stop us” on a public highway, and when within just feet of the Knight pulled his pistol and fired, clipping Knight’s right ear.[ii] Knight returned fire, striking Brown near the heart. According to Wilson, Brown attempted to get to his feet, exclaiming “hold a minute and I think I can make it,” before collapsing in death.[iii] Wilson retreated in the direction of Grafton as a second shot clipped the heel of his boot.

One account claims that the killing of Brown was in regards to a pre-war feud between Knight and Brown, Knight promising to kill Brown if he ever had the chance after Brown had assisted in his arrest. Knight made a statement of the incident to Colonel Porterfield the following morning, claiming he “halted Brown two or three times, but he didn’t stop, and came up and shot me through the ear and it made me so mad I shot him. I hope I didn’t do anything wrong…,” to which Porterfield responded that if Knight had done anything wrong it was “in not shooting sooner.”[iv]

Brown’s body was conveyed to Fetterman. The next morning an envoy from Grafton requested its return, which Colonel Porterfield denied. The Grafton Guards started towards Fetterman, intent on retrieving the body by force, when they met a group of the Letcher Guards returning Brown’s body on a railroad hand-car. His body was laid out at the Grafton Hotel while a coffin was procured, during which time many local residents passed in view. Brown’s body was removed to a nearby graveyard where he was buried by his company with military honors. Two days later the company would muster into Federal service at Wheeling, becoming Co. B 2nd Virginia Infantry. The Letcher Guards would be mustered as Company A 9th Battalion Virginia Infantry, later designated Co. A 25th Virginia Infantry.

(Authors photo)

In 1903 Brown’s body was exhumed and re-interred at the National Cemetery in Grafton. The following year an impressive obelisk monument was erected over his grave, easily identified above the many surrounding government-issued headstones. In 1928 the local tent of the Daughters of Union Veterans placed a stone market and tablet on the spot Brown was killed adjacent to the railroad tracks at Fetterman Crossing. The marker has since been moved to a more visible location on Route 50.

Neither Brown nor Knight were uniformed or yet mustered into service. It’s also possible that prewar animosity contributed to the argument and killing of Brown. The incident wouldn’t even rise to the classification of a skirmish. And yet both men had enlisted for their respective causes and were discharging their duties at the time. And for that – for my purposes, at least – we give Thornsbury Bailey Brown the dubious distinction of first Federal soldier killed by a Confederate soldier during the American Civil War.

[i] Reader, Frank S. History of the Fifth West Virginia Cavalry, Formerly the Second Virginia Infantry, and of Battery G, First West Va. Light Artillery. New Brighton, PA: Daily News. 1890

[ii] Lesser, Hunter. Rebels at the Gate: Lee and McClellan on the Front Line of a Divided Nation. Sourcebooks, Inc. 2005.

[iii] Haselberger, Fritz. Yanks From the South! Baltimore, MD: Past Glories. 1987.

[iv] ibid

Great story, Eric.

Peyton Anderson, of Amissville, VA died of a gunshot wound in Fairfax. I don’t have the date at hand, but some think that he was a First! He was supposed to have been on picket when he and a fellow soldier were surprised by a Union cavalry unit. He and his colleague fled. A Union troop hit Peyton and he soon expired. There is a marker located just NW of the Fairfax Circle on highway Rt 50.

Hi Robert,

Anderson was wounded May 27, 1861 at Fairfax, VA. He survived but has been regarded as the first Southern soldier to shed blood during the war. I’d be inclined to give that honor to Daniel W.S. Knight after he was wounded by Thornsbury Brown, but an interesting story nonetheless. Thanks for sharing!

Thanks for bringing this nearly forgotten tale to our attention. As for “the first man to spill his blood due to enemy action during the Civil War,” I propose Nick Biddle.

I read this with interest since Thornsbury Brown is my 3G Grandfather. After his death, Thornsbury’s wife Nancy moved the children to Iowa to live among relatives of hers. Nancy stayed in Iowa. Some of the kids, including my 2G grandfather, Jacob, moved back to West Virginia settling in Morgantown area. I’m curious as to why you think the picture is misidentified. This is the same picture my grandmother showed me and said was Thornsbury, but I don’t know the origin of the photo she had. Maybe she was just misinformed as well. Her grandfather Jacob was only a year old when Thornsbury was killed.

Hi Suzanne,

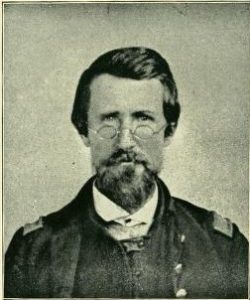

Nice to hear about your connection with Mr. Brown! In regards to the photo there are a few things that jump out at me as to why I don’t believe this to be him. The Grafton Guards were not armed and equipped until reaching Wheeling, which occurred several days after Brown’s death. More than likely he was simply wearing his civilian clothes when he was shot. You’ll also notice an inverted V on the cuff of each sleeve…those are what was called a service stripe or veterans stripe. Regulations permitted these for soldiers who had been in the service for five years, but you also see some veteran volunteers attaching them to denote their years of wartime service. He would not have been wearing those at the time of his death. This photo just appears to me to have been taken a bit later in the war.

Hello Suzanne,

I am also related, his youngest grandchild is my Great Grandmother Helen Rogers of Fairmont, WV. After reading your comment, we are wanting to see our family connection! Love to get in touch with you.

Thanks!

Heidi Huber

Nice to hear from you Heidi! My email is suziestjohn@gmail.com . Feel free to contact me directly.

I have been told this is my Great great great grandfather also Our family Names are Bailey and Parsons my Grandmother is Kathleen Virginia Parsons The Parson West Virginia Parson and My Grandfather Is Chauncey A Bailey of West Virginia I am Curious how. We are Related. I might even Be related to some of these people commenting here? My Grans Has Passed and She Had the Family Book which my Aunt Has now.. I’m sure the answers are in there ..

Thornberry Bailey Brown is my great-great-grandfather on my paternal grandfather’s side.

Daniel Knight was my 3rd Great Grandfather. I discovered this story through my family research…such a small world!

That is amazing. Wonder if they did have some personal argument before the skirmish? I just found a photo of my GG grandfather visiting his dad’s memorial at Grafton probably in the 1920s.

I am also a descendant of Daniel Knight. My sister was at the family reunion & heard the story. There was bad blood between these two regarding theft of a cow. Thornsbury Bailey Brown accused Daniel Knight of stealing it & had him arrested & put in jail. Apparently they couldn’t prove it & let him go. Days after that is when skirmish at Fetterman occurred.