Kill General Lee: A Yankee Officer Opposes Reconciliation

We’ve all heard the simplified story. Confederate veterans roll up their battle flags at Appomattox and Robert E. Lee charges them with being good citizens as they return to the United States. Impressed by this act of good faith and awed by their antagonists’ hard fighting, Union soldiers graciously accept their foe’s surrender and return home. Mutual admiration replaces animosity as the country reunites. Add in a couple of old veterans shaking hands over a wall at Gettysburg.

Captain Maurice Leyden thought otherwise. So too did many of his comrades, whose opinions run contrary to the rosy versions of a reconciled nation. In order to understand the Reconstruction period we must look past the idyllic reunion narrative. Leyden’s letters in the spring and summer of 1865 show a deep bitterness and hatred toward the former Confederacy, particularly its leaders.

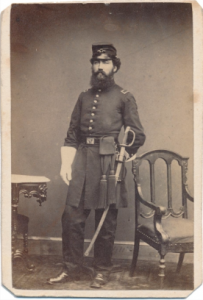

Maurice Leyden was born in Collamer, Onondaga County, New York, on October 18, 1836. A local historian noted his “early life was spent upon his father’s farm, where he developed a strong and rugged constitution.” Leyden attended Cazenovia Seminary and afterward studied under Dr. Amos Westcott, a prominent Syracuse dentist. He worked in that profession until the Civil War broke out. On June 13, 1861, Leyden mustered in as second lieutenant of Company B, 3rd New York Cavalry. The regiment saw service in North Carolina before transferring to the Army of the James in 1864 for operations around Bermuda Hundred and Petersburg.

His letters to his sweetheart, Margaret L. Garrigues, seem to offer great insight into the operations of the Army of the James cavalry and Leyden’s own political views. I regret they do not have a single institutional home. Instead, they are scattered throughout various archives and auction houses. One identified letter from September 13, 1864 commented about the upcoming presidential election. Though he viewed George McClellan as a “true patriot” who “loves the Old Flag still,” Leyden did not agree with Little Mac’s willingness “to have the Union as it was,” regarding slavery. “Most of us who have fought,” Leyden wrote, “are not willing to have the Union as it was… we think the Emancipation Proclamation a military necessity… and wish to blot out the cause of this unholy war—African Slavery… so we only know of it in history.”[1]

On October 7, 1864, Leyden was captured along Darbytown Road outside Richmond.[2] During his five months as a captive, Leyden suffered in the confines of Libby Prison as well as prison camps in Danville and Salisbury. The experience resonated in his later writings. He was paroled on February 22, 1865 and returned home awaiting exchange. There he took the opportunity to marry Maggie before his official exchange on April 1st. He returned to Virginia after the final campaign began.

April 1865 was not an easy time to track down individual units, so Leyden remained at City Point awaiting word from his regiment. He continued writing to his new wife during this time, including a May 7th letter discussing what he noticed during a visit to nearby Petersburg.

Yesterday Col. Bradley furnished me with a good span of horses, a covered carriage, and driver, so I went up to Petersburg on my own account – had a very pleasant time, only it was very hot and dusty – I passed over some of the same ground that it would not have been healthy for me to have done one year ago this time – verily it is said what changes take place in a short time. I was somewhat disappointed in the appearance of Petersburg as to the effect of Gen. Grant’s “Salutes” in fact there [were] not many of the buildings injured. The city is full of “gray backs” but most of them have learned to behave themselves – they are all very poor and have nothing to eat except the rations issued to them by our government.

He seemed to regret that more damage had not been done to Petersburg, but saved his most bitter opinion for the former Confederate commander. “I was told that Gen. Lee drew rations every day for his family – a good idea to feed the man who had killed and starved to death so many thousand of our poor men – d—d him I will sacrifice my own life at any moment to kill him – for the sake of my friends I hope that I may never see the arch traitor.”[3]

Now a captain, Leyden remained in Virginia during the summer and transferred to the 1st New York Mounted Rifles. While many comrades returned home, the prolonged assignment did not bother him. He longed for an opportunity to continue fighting. On July 20th he wrote about an anticipated expected visit to Smithfield. A group of about a hundred former slaves had attempted to visit the areas around their old plantations on July 4th to mark the nation’s Independence Day. Their arrival by boat was met with an angry mob who hoped to turn them away. The excursion had expected possible violence and were accompanied by twenty-five armed cavalry escorts. A small scuffle broke out between the Federal soldiers and Smithfield residents and military authorities ordered more troops into the area to restore order.

Leyden relished the opportunity. “Above all other it is just the place where I have wanted to go. I have wanted to kill a rebel ever since I returned from prison and now I think that I shall have an opportunity, for they show fight there… I only hope they will keep up their fighting propensities until I get there as I would give one years pay to get in a good fight once more with the rebs before I leave the service.”[4]

Despite his blustering, Leyden peacefully remained in Virginia as part of the Reconstruction garrison and eventually returned to New York, where he opened a dental practice in Rochester and a dental machinery manufacturing business. His wife Maggie joined Susan B. Anthony’s suffrage movement. “I think they are right & as citizen can vote beyond a doubt,” Maurice wrote in his diary on the eve of the 1872 election.[5] He participated in veteran associations and reunions until his death in 1906.

“In his social relations Major Leyden was a companionable and delightful man,” his obituary stated. “His attractive personality had drawn about him from his earliest youth loyal friends. With strangers he was reserved, but his courtesy was such as to attract even those with whom he was but slightly associated.”[6]

Maurice Leyden has no great fame or renown, but the immediate postwar rage put to pen by an intelligent, progressive veteran offers a stark contrast to the romanticized notion of harmony at the end of the Civil War.

Sources:

[1] Maurice Leyden to “My Darling Little Pet,” September 13, 1864, Lot #354, January 30, 2014 Auction, Raynors’ Historical Collectible Auctions, Burlington, NC.

[2] For the best study of this battle, see part 1 of Hampton Newsome, Richmond Must Fall: The Richmond-Petersburg Campaign, October 1864 (Kent, OH: The Kent State University Press, 2013).

[3] Maurice Leyden to “My dear wife,” May 7, 1865, Lot #822, September 9, 2014 Auction, Alexander Historical Auctions, Chesapeake, MD.

[4] Maurice Leyden to “My Darling Little Pet,” July 20, 1865, Lot #821, September 9, 2014 Auction, Alexander Historical Auctions, Chesapeake, MD.

[5] Maurice Leyden diary, November 4, 1872, Maurice Leyden Collection, Special Collections, Binghampton University Libraries, Binghampton University, State University of New York.

[6] “Successful Life Comes to Close,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, August 16, 1906.

One can understand his individual sense of anger, especially following his role as a war captive. I wouldn’t make too much of it as an example, as many other intelligent, progressive individuals embraced the very “romantic” post war idyllic view in an effort to deal with the sustained horror of the war, and give it ultimate resolution.

Not being immediately ‘forgiven’ of an enemy is perfectly understandable regardless of the conflict. Often it just takes some time for such animosities to be purged, but for some they never lose their hostilities.

This begs a question: Are there any instances of such retribution against Confederate military leaders and/or politicians in the post War years? Were there any assassination attempts conjured up or at least discussed that targeted people like RE Lee?

I can’t think of any Union soldiers or former Unions soldiers in the South murdering Confederate officers. What they did try to do was have them jailed or possibly executed for murder or war crimes. Their efforts were overwhelmingly unsuccessful because there were too many local white people who wouldn’t countenance it. They did get some bushwhackers hanged (murdered too many good white folk) and the Swiss emigre colonel from Andersonville, but they couldn’t get the likes of Lee or Forrest.

One ex-Confederate officer who was murdered after the war was St. John Richardson Liddell. He was murdered by a man or a gang of men who had been his personal/familial enemies before the war. Their feud picked right back up after the war and it ended badly for Liddell. It was kind of a Louisiana version of the Hatfields and McCoys.

Great question. The only thing I’m aware of is the Confederate duel involving Lucius Walker, and the ferocious post war squabbling among some of the southern military leaders.

The survivors of prison of war camps, North and South, tended to be the loudest critics of the reunion narrative. That narrative of course had its limits. Even Confederate battlefield monuments were often opposed by old veterans. Yet, in the end the war was first and foremost about the union, and as such reuniting the nation was objective number one.

“Maurice Leyden has no great fame or renown, but the immediate postwar rage put to pen by an intelligent, progressive veteran offers a stark contrast to the romanticized notion of harmony at the end of the Civil War.” – History shows that being bloodthirsty, vengeful, and cruel is not a conservative or progressive monopoly. Leyden’s feelings would have been approved of in the Russian Civil War by both sides of that tragedy.