The Trust’s 2019 Teacher Institute: The Garry Adelman 1865 Photo Extravaganza!

Garry Adelman bills his photography presentations as “extravaganzas,” and he’s not stretching the point. Still photographs flash on a big screen in the corner of the room, but Garry’s ebullience as he talks about them radiates with the energy of a one-man Spielberg blockbuster. “I have a three-hour talk to give in 40 minutes,” he says to a laugh from the audience—and he successfully pulls it off.

Garry Adelman bills his photography presentations as “extravaganzas,” and he’s not stretching the point. Still photographs flash on a big screen in the corner of the room, but Garry’s ebullience as he talks about them radiates with the energy of a one-man Spielberg blockbuster. “I have a three-hour talk to give in 40 minutes,” he says to a laugh from the audience—and he successfully pulls it off.

Garry, chief historian of the American Battlefield Trust and co-founder of the Center for Civil War Photography, talks about Civil War photos the way a five-year-old talks about Christmas morning—an odd comparison, perhaps, considering the grim subject matter of some of the photos except that, for Garry, each image holds surprises and secrets and fascinating details, and he is excited to share. Looking at a photo with Garry is like a voyage of discovery.

Each year, he kicks off the American Battlefield Trust’s National Teacher Institute with one of his extravaganzas. They’re crowd-pleasers, but along the way, Garry offers a dozen different suggestions for ways teachers can use Civil War images in their classrooms—not just as mere illustrations but as sources of inquiry. Again, the word “discovery” comes to mind.

“Whatever you’re trying to teach in the Civil War, there’s probably a photograph of it—sometimes hundreds of photographs,” Garry says. “If you’re trying to teach something from the Confederate perspective, there are probably not as many. If you’re trying to teach something from the West, there are probably not as many.” But there were 10,000 photos taken outside during the war—most in the north, most in the east—including 97 photographs of the dead.

This year’s extravaganza focuses on the final year of the war because, later in the week, some T.I. participants will visit nearby Averasboro, Bentonville, and Bennett Place. “1865 has lots of good material for use in a classroom, even for teachers who only have a single day to cover the war,” Garry points out.

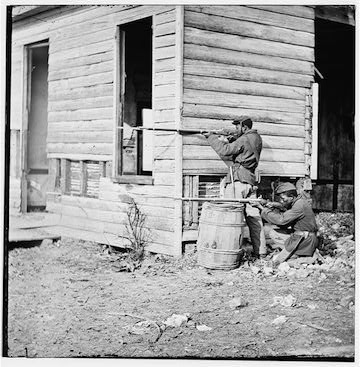

He weaves a story of the war’s final months, showing off a variety of photos that not only illustrate the main points of his story but which contain stories of their own. He shows an image of United States Colored Troops taken at Dutch Gap, Virginia—only to show an additional image that proves the USCT image was posed.

He shows an image of High Bridge taken after the Confederate retreat through Farmville, Virginia. “They call it ‘High Bridge’ because if you fall off it, you die,” Garry says. “And yet look!” He zooms in on men perched high on the rail of the bridge, sitting and even standing on the precipice. “Why would you risk your life to pose for a photo where nobody even knows it’s you? I could do a whole program on the idiocy of Civil War daredevils.”

He shows an image of High Bridge taken after the Confederate retreat through Farmville, Virginia. “They call it ‘High Bridge’ because if you fall off it, you die,” Garry says. “And yet look!” He zooms in on men perched high on the rail of the bridge, sitting and even standing on the precipice. “Why would you risk your life to pose for a photo where nobody even knows it’s you? I could do a whole program on the idiocy of Civil War daredevils.”

The image gives Garry the opportunity to stress the high resolution of most Civil War images. The glass-plate photography captures detail a modern digital image can’t. “You can see the stitches in their coats,” Garry marvels. “You can see their fingerprints.

He points people to loc.gov, a repository that holds thousands and thousands of such photos. “It’s an unparalleled opportunity for students to explore,” Garry says.

Another resource he shares is civilwarphotosleuth.com, a crowd-sourced database of portrait photos that uses facial-recognition technology to identify unidentified soldiers and civilians.

In his story of the war’s last months, Garry rolls through the fall of Richmond, which “becomes the second most-photographed city of the Civil War” (after D.C.) when photographers flooded into the Confederate capital. At Libby Prison, converted to hold Confederate prisoners after the fall of the city, photos show the arms and legs of men lined up inside, pushing against the bars for any feel of fresh air.

An image from April 14, 1865, shows the restored American flag rising up once more to fly over Fort Sumter. “It was a consequential day,” Garry points out, because in D.C., he reminds us, Abraham Lincoln visits Fords Theater.

Beyond, he shows images of the Sultana, the VIP stand at the Grand Review, recently freed slaves.

At the execution of the Lincoln conspirators, photos show coffins of the condemned stacked next to the scaffold; the shovels used to dig their graves are stacked up against the wall.

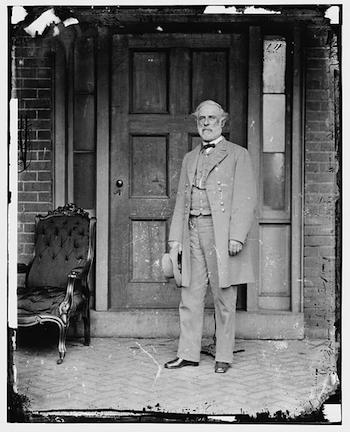

He shows images of Lee and Grant. “Lee and Grant are the two most important people who made sure the peace went as well as it did,” Garry says. It didn’t go as well as it could have, he admits, but it could have gone worse.

Despite such somber notes, Garry manages to make the overall extravaganza a tremendous amount of fun. He shows a series of self-depreciated photos where he’s standing in front of Lee’s Richmond home, recreating time and time again, over a span of decades, the famous pose of Lee standing there. He jokes about Abraham Lincoln and stovepipe hats, showing an image of ersatz Lincolns all in stovepipe hats except for Lincoln himself, who’s not wearing one. He shows images of people holding vigil around Lincoln’s death bed, with each image showing a bigger room and more witnesses on the scene, and more and more, until finally it’s a soccer stadium full of people. “It turns out, everyone is there!” Garry laughs.

Despite such somber notes, Garry manages to make the overall extravaganza a tremendous amount of fun. He shows a series of self-depreciated photos where he’s standing in front of Lee’s Richmond home, recreating time and time again, over a span of decades, the famous pose of Lee standing there. He jokes about Abraham Lincoln and stovepipe hats, showing an image of ersatz Lincolns all in stovepipe hats except for Lincoln himself, who’s not wearing one. He shows images of people holding vigil around Lincoln’s death bed, with each image showing a bigger room and more witnesses on the scene, and more and more, until finally it’s a soccer stadium full of people. “It turns out, everyone is there!” Garry laughs.

Garry heads into the home stretch by carrying the story of the war forward with the creation of national cemeteries, veterans commemorating their service, and the eventual origins of the Civil Rights movement—all legacies that remain with us today. He also talks about the rise of the modern preservation movement. “The American Battlefield Trust has saved 5,000 acres of 1865-related land,” he says, part of more than 51,000 acres the Trust has preserved overall.

Finally, he brings up an image of a crowd beneath a shaded grandstand. All faces look at the camera. “Look at the people in these pictures,” Garry says, speaking not just of the image onscreen but all the images he’s shown. “They’re just like us. They’re just like us.”

It’s a pitch-perfect ending to the extravaganza, which has proven illuminating, thought-provoking, and wicked funny. He has also managed, in his 40 minutes, to cover 152 slides. “Wow, that was really fast,” he says in a feigned post-extravaganza daze. “That’s because it was all just one sentence!”

An extravaganza of a sentence it was.