Surviving Quantrill’s Raid on Lawrence

August 21 marked the 156th anniversary of Missouri guerrilla chieftain William C. Quantrill’s infamous Raid on Lawrence, Kansas – one of the bloodiest and most significant irregular attacks against civilians during the American Civil War.

A center of abolition and home to their rival Jayhawkers, Lawrence became a prime target for an attack by Quantrill’s Raiders in the late summer of 1863. The border war between Missourians and Kansans had simmered since Bleeding Kansas, the violent aftermath of the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854.

By this point in the war, however, the bloodshed had reached its pinnacle. Quantrill’s men were outraged by two particular events: the Sacking of Osceola by Senator James Lane’s Jayhawkers and the deadly collapse of a Kansas City prison housing the female relatives of Missouri guerrillas. The combination of those events and the rivalry with Kansas forced Quantrill and his men to act.

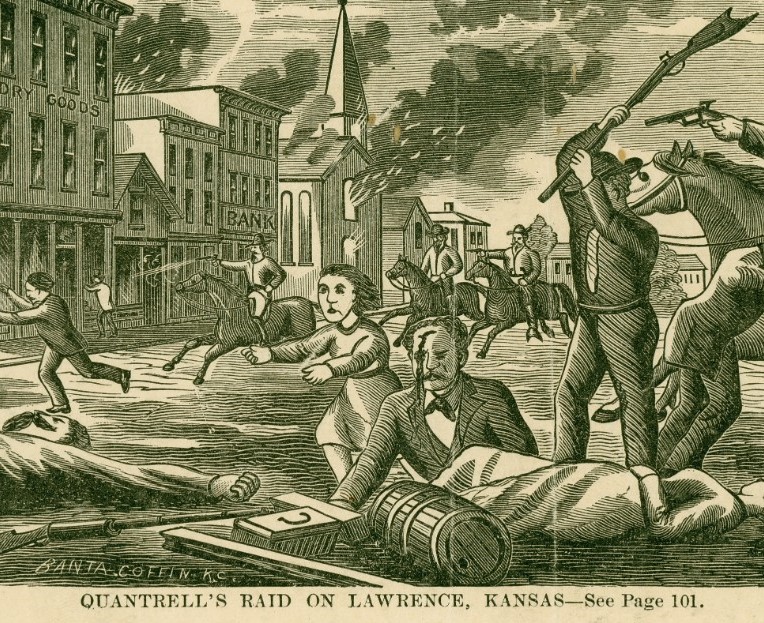

With his own men and local independent guerrillas, Quantrill’s force totaled approximately 450 men and armed with multiple revolvers each. Just hours before the attack at dawn on August 21, they rendezvoused just miles from where Lawrence sat unaware of the impending attack.

Around 5:00am, Quantrill’s men launched their attack from the southeast of town. Lawrence’s civilians and larger community would never be the same.

For H.M. Simpson, a Lawrence banker, the attack against his community was harrowing. Just days after the attack, he wrote this vivid and chilling account to a friend in Williamsburg, Massachusetts that comes from the Kansas Historical Society.

“Quantrill’s men came in at the south east part of town a little before sunrise, and commenced murdering our people at once. Judge Carpenter was pursued all over his house and finally shot repeatedly while in his wife’s arms. They raised Mrs. Sargent’s arm in order to make a fatal shot at her husband. Mrs. Fitch was not allowed to pull her husband’s body out of the burning house, but was compelled to stand by and see the corpse consumed. Men were repeatedly shot with children & even babies in their embrace. Mr. Dix purchased his life by paying $1000. As soon as the money was handed over he was killed. These instances are not the worst that occurred but are given as a fair sample of what transpired.”

Seeing the murder of neighbors and friends, he and his family fled into a nearby cornfield to hide. He wrote, “My father was very slow to get into the cornfield. He was so indignant at the ruffians that he was unwilling to retreat before them. My little children were in the field three hours. They seemed to know that if they cried the noise would betray their parents whereabouts, and so they kept as still as mice. The baby was very hungry & I gave her an ear of raw green corn which she ate ravenously.”

Writing that, “almost all the business men of our city are penniless,” Simpson continued to describe the shear destruction of his livelihood. “I lost everything, and have to commence life again at the bottom of the ladder. Our firm will commence business at once. We do not intend to abandon the place no matter what will happen. We feel that we should make no complaints at the destruction of our having saved our lives.”

Simpson concluded his letter by asserting that he had “never learned that any body of free state men ever performed such fiendish acts as those which we witnessed on the 21st of August.”

Ultimately, 150 men and boys were killed in Lawrence, Kansas in less than four hours that morning by Quantrill’s Raiders. It was arguably the deadliest attack against civilians along the Missouri-Kansas border during the war, which led to harsh repercussions by Federal authorities under Brig. Gen. Thomas Ewing of the District of the Border; specifically, with Order No. 11. No matter which side of the border someone lived on, their lives were many times in shambles. The Simpson letter reveals that exact point and shows the brutality of guerrilla violence along both sides of the border.

Sources:

Letter from H.M. Simpson to Hiram Hill, September 7, 1863, Manuscript Collection, Kansas Memory, Kansas Historical Society, https://www.kansasmemory.org/item/213271.

The raid by the Jayhawkers and the the loss of their female relative’s set the stage for a brutal retaliation.

I never heard that my great, great grandfather, Ralph C. Dix, paid $1k to have his life spared. He was shot by Quantrill’s raiders in cold blood as he walked with my grest, great grandmother walking down street in front of Dix Home.

….David Edward Dix