An Ancient and Fearsome Weapon: The Ram

The ram—the main armament of sleek and swift Greek triremes powered by 180 rowers—turned back a Persian invasion at the Battle of Salamis in 480 BC and launched Western Civilization.

Rowing galleys ruled the Mediterranean for two more millennia, the last major engagement being at Lepanto in 1571 when European kingdoms thwarted another invasion from the east, this time the Ottoman Turks.

Then Europeans perfected the ocean-going, square-rigged, sailing vessel, armed it with their new cannons, and went exploring, conquering, and colonizing. The ram had no application on a sailing ship.

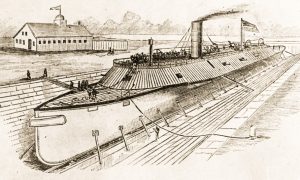

In the spring of 1862, the ancient weapon was resurrected to repel a Northern invasion. It was a 1500-pound cast iron beak on the stem of the ironclad CSS Virginia, now pushed by steam and propeller. Every man-of-war in the United States Navy was imperiled.

Confederate Secretary of the Navy Stephen R. Mallory instructed Captain Franklin Buchanan: “The Virginia is a novelty in naval construction, is untried, and her powers unknown, and the Department will not give specific orders as to her attack upon the enemy.”

Confederate Secretary of the Navy Stephen R. Mallory instructed Captain Franklin Buchanan: “The Virginia is a novelty in naval construction, is untried, and her powers unknown, and the Department will not give specific orders as to her attack upon the enemy.”

The secretary did, however, encourage him to test the ram. “Like the bayonet charge of infantry,” this mode of attack would compensate for scarcity of ammunition. It would be formidable even without guns.[1]

On the morning of March 8, Virginia sallied forth to take on Union warships in Hampton Roads. “A great stillness came over the land,” wrote one Confederate navy officer. Caps and handkerchiefs waved from river banks, “but no voice broke the silence of the scene; all hearts were too full for utterance; an attempt at cheering would have ended in tears, for all realized the fact that here was to be tried the great experiment of the ram and iron-clad in naval warfare.” Many thought Virginia would “sink with all hands enclosed in an iron-plated coffin” as soon as she rammed a vessel.[2]

Virginia plodded up channel toward the sailing frigates USS Cumberland and USS Congress laying placidly at anchor off Newport News Point. Virginia’s Lieutenant John R. Eggleston had served as midshipman on both ships. “The drum and fife are sounding the call to quarters,” he recalled, as the same summons echoed across the water from the foe. “We go quietly to our stations, cast loose the guns, and stand ready for the next act in the drama.”[3]

A young Congress sailor named Frederick H. Curtis watched the Rebel ram approach. “Every eye on the vessel was on her. Not a word was spoken, and the silence that prevailed was awful. The time seemed hours before she reached us.”[4]

Virginia headed straight for Cumberland, exchanging broadsides with Congress as she passed. “The action soon became general,” reported Buchanan, “the Cumberland, Congress, gunboats and shore batteries concentrating upon us their heavy fire, which was returned with great spirit and determination.”[5]

Lieutenant Eggleston: “Scarcely had the smoke [of the broadside] cleared away when I felt a jar as if the ship had struck ground.” Virginia burst through the heavy anti-torpedo spars floating around Cumberland’s bow and rammed her almost at right angles. “The noise of the crashing timbers was distinctly heard above the din of battle,” wrote Lieutenant Catesby Jones, Virginia’s executive officer. “There was no sign of the hole above water. It must have been large, as the ship soon commenced to careen.”[6]

Cumberland tumbled heavily to port and began to fill rapidly. Lieutenant Robert D. Minor passed along Virginia’s gundeck waving his cap, calling out: “We’ve sunk the Cumberland.” At his aft pivot gun, Lieutenant Wood recalled: “The blow was hardly perceptible on board…. The Cumberland continued the fight, though our ram had opened her side wide enough to drive in a horse and cart.”[7]

Cumberland let off another broadside just as she was struck. One shell exploded at Virginia’s bow gun port; fragments tore up the gun carriage, killing two and wounding twelve. Another struck a loaded 9-inch Dahlgren blowing off the muzzle and firing the gun. Another barrel was lopped off at the trunnions, so short that each subsequent discharge set the wood of the gun port on fire. Crews continued to load and fire the battered weapons.

Buchanan immediately backed Virginia’s engines. The propeller thrashed the water, but the two big hulls stuck together, recorded Eggleston, like “two mad bullocks with their horns locked.” As Cumberland settled, the ironclad’s bow was twisted and pushed down several feet. Suddenly the ram broke off and Virginia surged free, sustaining three point-blank broadsides in the process.[8]

Two gunners were killed and five wounded when a Federal shot severed the exposed anchor chain on the bow, causing it to whip inboard. Virtually all external appurtenances were swept away while the smokestack was riddled. Eggleston: “I have often thought since that if the prow had been held fast we would have gone to the bottom with our victim.”[9]

Brigadier General R. E. Colston, commanding Confederate forces on the south bank four miles away, watched in amazement. “I could hardly believe my senses when I saw the masts of the Cumberland begin to sway wildly.” Hordes of civilians and soldiers rushed to the shore to behold the spectacle. “The cannonade was visibly raging with redoubled intensity, but, to our amazement, not a sound was heard.” A strong March wind blew direct from them toward Newport News. “We could see every flash of the guns and the clouds of white smoke, but not a single report was audible.”[10]

On Cumberland, they frantically worked the guns and the pumps. An exploding Rebel shell took off a gun captain’s legs at the knees and an arm at the shoulder. As he fell, the dying man grabbed the firing cord with his remaining hand and fired the gun. “Don’t mind me boys, stand by your guns to the last,” he said. Down in the magazine, they were still passing powder charges up as the water reached chest high.[11]

Marine Daniel O’Connor from Staunton, Virginia, was a loader on a lower deck gun. In a letter home, he described seeing from his port every shell Virginia fired. “You could hear them cheer but you could not see them. I could hear them laugh, which was aggravating to us in that perdicament.” Several men tried to board the Rebel ship, “but it was no go. You could not step on the quarterdeck without walking through blood. Men’s legs in one place arms in another.” [12]

According to O’Conner, a Virginia officer called over to Lieutenant Morris asking him to surrender, but Morris retorted: “Dam[n] you, you coward you have made a slaughter house of the ship. We will sink with our colors first.” “Sink it is,” replied the Confederate.

By 3:35 p.m., water had risen to the main hatchway as the ship canted. Lieutenant Morris: “We delivered a parting fire, each man trying to save himself by jumping overboard.” Survivors and walking wounded scrambled up from below, but others in sick bay and on the berth deck were so mangled they could not be moved.[13]

The deck tilted steeply; one of the huge guns slammed into O’Conner’s shoulder knocking him down. “I picked myself up as quick as possible & got out the porthole just as the water was commencing.” Sitting on the ship’s side, he removed his coat and was taking off his shoes when he found himself up to his neck in water. The marine struck out for shore and was picked up by a boat.[14]

Acting Master William Kennison oversaw Cumberland’s forward pivot gun. “There was no sign of flinching,” he recorded. “Even at the instant of collision, a shot was fired…. After she had struck us, I did not stop to look at her, but superintended the loading, to give her a few more of the same sort.”

Shells bursting around them, Kennison and his crew fought until ordered to abandon ship, by which time the forward deck was under water. “With a last shot at the enemy I left my quarters to look out for a chance to save myself.” He jumped and was rescued by a tug. “That day I had three escapes—from shot and shell, from drowning, and from [fire and smoke].” Some piled into boats; many swam; others climbed the rigging where they remained until firing ceased.[15]

General Colston: “After one or two lurches, [Cumberland’s] hull disappeared beneath the water. Most of her brave crew went down with their ship, but not with their colors, for the Union flag still floated defiantly from the masts, which projected obliquely for about half their length above the water after the vessel had settled unevenly upon the river-bottom. This first act of the drama was over in about thirty minutes, but it seemed to me only a moment.”[16]

Cumberland lost 121 killed and wounded from a crew of 376, amongst whom was Methodist minister John L. Lenhart, the first U.S. Navy chaplain to lose his life in battle. Concluded Virginia’s Lieutenant Wood: “This action demonstrated for the first time the power and efficiency of the ram as a means of offense. The side of the Cumberland was crushed like an egg-shell.” [17]

Union soldiers discovered wreckage and collected souvenirs along the shoreline for months. In late May, a surgeon walking the beach at dusk quietly smoking his pipe came upon the remains of a Cumberland sailor floating at the water’s edge. He pulled it up on the sand, covered it with seaweed, and stood by the mound “thinking of the poor nameless thing beneath” until the provost marshal arrived. “Then, was I homesick?” he thought. “Only the moon and the stars and the night could testify.” A Union nurse observing the warship’s still-visible masts months later called them a “fit monument—grave and monument as well of heroes.”[18]

The ram occasionally prevailed during the war, notably at the Battle of Memphis in June 1862 when Union river rams destroyed a ragtag Confederate squadron. For the brief period that iron armor dominated gunnery, the ram could be effective, but by the late 19th century, long-range, breech loaders rendered this ancient weapon obsolete.

Excerpts from book in progress for the Emerging Civil War Series: Unlike Anything That Ever Floated: The Monitor and Virginia and the Battle of Hampton Roads, March 8-9, 1862.

[1] S.R. Mallory to Flag-Officer Franklin Buchanan, February 24, 1862, in Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion, 2 series, 29 vols. (Washington, D.C., 1894-1922), series 1, vol. 6, 776-777. Hereafter cited as ORN.

[2] PCaptain William Harwar Parker, Naval Officer: My Services in the U.S. and Confederate Navies 1841-1865 (Big Byte Books, 2014), loc. 3762 to 3776 of 5575, Kindle.

[3] Captain Eggleston, “Captain Eggleston’s Narrative of the Battle of the Merrimac,” in Southern Historical Society Papers, 52 vols., vol. 41 (September 1916), 170.

[4] Frank Stedman Alger, “The ‘Congress’ and the ‘Merrimac:’ The Story of Frederick H. Curtis, A Gunner on the ‘Congress,’” The New England magazine 19 (February 1899), 688.

[5] Franklin Buchanan to S. R. Mallory, March 27, 1862, in ORN, series 1, vol. 7, 44.

[6] Eggleston, “Captain Eggleston’s Narrative,” 171; Catesby ap Roger Jones, “Services of the Virginia,” in Southern Historical Society Papers, 52 vols., vol. 11 (January-December 1904), 68.

[7] Eggleston, “Captain Eggleston’s Narrative,” 171; John Taylor Wood, “The First Fight of Iron-Clads,” in Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, Being for The Most Part Contributions by Union and Confederate Officers. Based Upon “The Century War Series.” Edited by Robert Underwood Johnson and Clarence Clough Buel, of the Editorial Staff of “The Century Magazine,” 4 vols. (New York, 1884-1888), vol. 1, 698.

[8] Ibid., 172.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Brigadier-General R. E. Colston, C. S. A., “Watching The ‘Merrimac,’” in Battles and Leaders, vol. 1, 712.

[11] William Keeler to Anna, March 30, 1862, in Robert W. Daly, ed., Aboard the USS Monitor: 1862: The Letters of Acting Paymaster William Frederick Keeler, U.S. Navy to His Wife, Anna (Annapolis, MD, 1964), 65.

[12] Daniel O’Conner to Timothy, March 13, 1862, in “Muzzle to Muzzle with the Merrimack,” Civil War Times 35 (June 1996), 67.

[13] O’Conner, “Muzzle to Muzzle with the Merrimack,” 67; Geo. U. Morris to William Radford, March 9, 1862, in ORN, series 1, vol. 7, 21.

[14] Ibid., 67.

[15] Kennison to Welles, March 18, 1862, ORN, series 1, vol. 7, 22-23.

[16] Colston, “Watching The ‘Merrimac,’” 712.

[17] Wm Radford to Gideon Welles, March 10, 1862, in ORN, series 1, vol. 7, 20-21; Wood, “The First Fight of Iron-Clads,” 703.

[18] Martha Derby Perry, ed., Letters from a Surgeon of the Civil War (Boston, 1906), 5-7; Harriet Douglas Whetten, diary entry for August 1, 1862, in Paul H. Hass, ed., “A Volunteer Nurse in the Civil War: The Diary of Harriet Douglas Whetten, Wisconsin Magazine of History 48 (Spring 1965), 213.

Fascinating article !

And building in England for the Confederate Navy were the Laird Rams, steel-hulled monsters specially designed to break the Union Navy’s blockade of the South. Fortunately, CSS North Carolina and CSS Mississippi were never delivered to the Confederacy.