The Importance of Finding the Original Source

When it comes to reading history, I’m a slow reader. Usually, every time I see a superscript number at the end of a sentence or paragraph, I’ll flip to the back of the book to see the source. I’m a research junkie so footnotes and endnotes continually whet my appetite for more sources about a particular subject.

This practice has saved me a few times and, more often than not, it plants an important reminder for historians right in front of my eyes: it is important to cite original sources so readers can find where the writer obtained their information and then read it for themselves. Sometimes, you might find that the meaning of the original source is vastly different than what the secondary source says.

Take Timothy J. Reese’s Sykes’ Regular Infantry Division, 1861-1864: A History of Regular United States Infantry Operations in the Civil War’s Eastern Theater. In terms of its subject matter, the book is unique in tackling the Army of the Potomac’s regular infantrymen. But there is one part of the book that I found particularly troubling.

In Reese’s section discussing the Regulars at Antietam, he sifts through the question of whether or not their attack under Hiram Dryer should have been pressed further against the Confederate center on September 17. To buttress his argument, Reese writes:

[Division commander George] Sykes reported his belief that “there is no doubt [Dryer] could have crowned the Sharpsburg crest,” then resorted to his usual stony silence.

I read this passage and immediately flipped to the back of the book. Sykes’ expression of this belief was new to me. Did Reese have some source I’d never seen before?

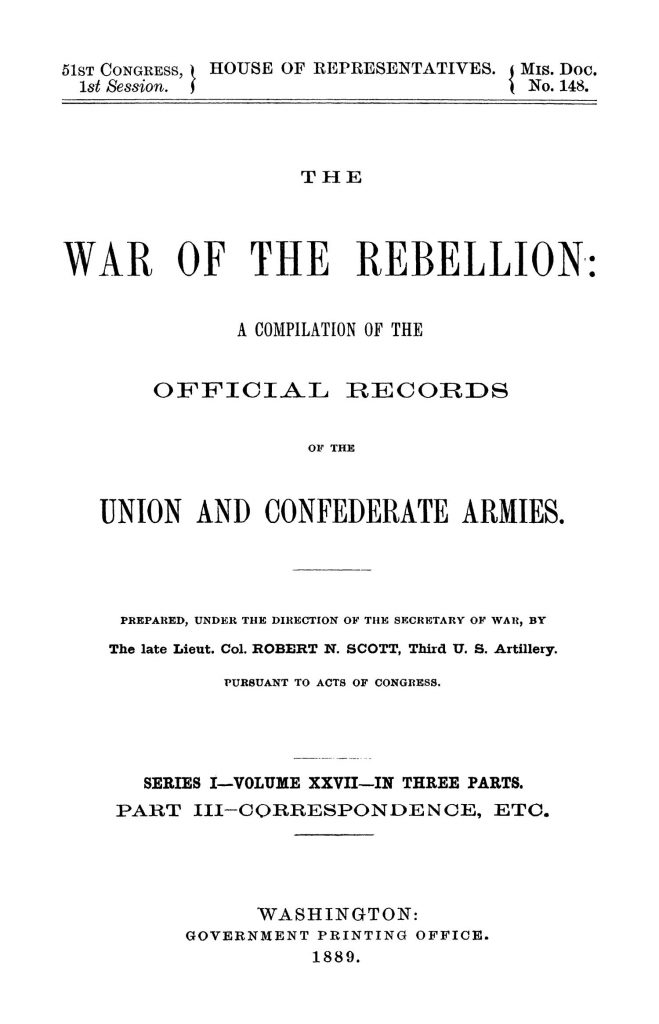

To the endnotes I went. Endnotes 29 stated Reese found this quote from Sykes in Volume 19, Part 1, of the Official Records of the War of the Rebellion, page 351. I sprang from my reading chair to grab my copy of the ORs and thumb through the pages to 351. It was Sykes’ official after-action report where Reese pulled the quoted passage.

But, when I read Sykes’ comments about the Battle of Antietam, his assessment of continuing the attack and the way Reese wrote it in his book were vastly different.

Let’s read Sykes’ quoted words again. “There is no doubt [Dryer] could have crowned the Sharpsburg crest.” Sykes’ meaning seems pretty clear, assured as he was of Federal success and disappointed that no further attack was made. However, what Sykes actually wrote tells a different story:

The troops under Captain Dryer behaved in the handsomest manner, and, had there been an available force for their support, there is no doubt he could have crowned the Sharpsburg crest.

Now that tells a different story about Sykes’ feelings regarding the attack and changes his meaning entirely.

I closed the ORs and went back to reading Reese’s book, but it served as an important reminder as a writer and historian: keep the context of the quotes you use in a book consistent with their original intent and, as Reese did, cite the original source so readers can read it for themselves.

Well said.

Regrettably I have found the same practice of partial quotes taken out of their OR context having the opposite meaning. Had the author included the next sentence the true original source intent would have been verified.

Kevin : This is an excellent post on a subject which doesn’t get discussed often enough. Too frequently we assume that an author has stated what is contained in a source with complete accuracy. Occasionally, however, I’ve done what you did and have found either some distortion or even flat out error. Especially in the former case it’s often not intentional but a subtle change/careless interpretation of what the source actually states. A separate issue is the occasional practice of citing an original archival source when the author actually accessed an annotated/edited version of the archival source.

Excellent post! It is worth checking sources no matter how long it takes. Dennis Frye discusses this in his book Antietam Shadows: Mystery, Myth & Mechanization. He also describes it in this video from C-Span 3 https://www.c-span.org/video/?452546-3/myths-battle-antietam.

Very apropos. A very well made point.

Well stated, Kevin, and useful reminder to all of us.

Vastly different? This is highly specious within three pages chronicling the incident, in fact nit-picking among collective participant command voices. With or without the additional report text you cite, Sykes nevertheless clearly knew that an immediate assault would have yielded crucial results irrespective of the availability of support troops, of which he knew nothing, to drive it home.

For elaboration see: http://antietam.aotw.org/exhibit.php?exhibit_id=371

A bald man should never split hairs.