Honoring General Milton S. Littlefield: The Right Thing to Do?

A few months ago, if I already don’t have enough on my plate, I decided to establish Shrouded Veterans with the goal to properly honor Mexican War and American Civil War soldiers buried in unmarked graves. One of these projects has led me to a question that I never thought I would find myself asking: Should a soldier be honored with a veteran marker based on his conduct before or after the war? My gut tells me that every soldier deserves a tombstone, regardless of whatever wrongs he committed during his lifetime. On the contrary, my consciousness advises against commemorating a man whose life was riddled with corruption and deceit. The individual who led me to this conundrum is Brevet Brigadier General Milton S. Littlefield.

A few months ago, if I already don’t have enough on my plate, I decided to establish Shrouded Veterans with the goal to properly honor Mexican War and American Civil War soldiers buried in unmarked graves. One of these projects has led me to a question that I never thought I would find myself asking: Should a soldier be honored with a veteran marker based on his conduct before or after the war? My gut tells me that every soldier deserves a tombstone, regardless of whatever wrongs he committed during his lifetime. On the contrary, my consciousness advises against commemorating a man whose life was riddled with corruption and deceit. The individual who led me to this conundrum is Brevet Brigadier General Milton S. Littlefield.

A Lincoln Man

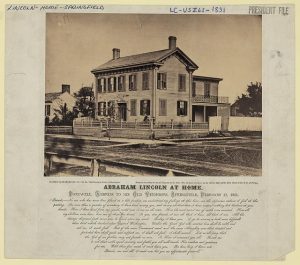

A Michigan native who relocated to Illinois after the death of his father in 1856, Milton Smith Littlefield befriended lawyer Abraham Lincoln while working as a newspaper reporter during the late 1850s. As a favor to a friend, Lincoln agreed to take on Milton’s brother, John, in his Springfield office to study law. In August 1860, Milton S. Littlefield rallied a body of pro-Lincoln supports – dubbed the Jersey County Wide Awakes – and marched them to Springfield. Serving as their captain, Littlefield led the Wide Awakes past Lincoln’s home and introduced each man of his company to his friend and the Republican presidential candidate.[1]

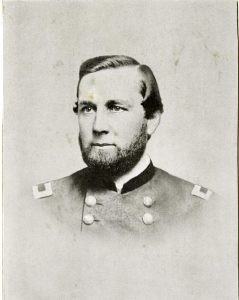

A month after the Civil War erupted, 30-year-old Milton S. Littlefield was elected a captain in the 14th Illinois Infantry in May 1861. He led his company at the Battle of Shiloh in April 1862, where he distinguished himself and received special mention from his regiment commander, Colonel Cyrus Hall. Sergeant J.A. Davis praised “the daring gallantry of Captain Littlefield, of Company F, who stood erect in front of his men, during the whole engagement, but escaped all injury, except having about three inches torn from the left shoulder of his coat, by a ball from the enemy.”[2]

In early November 1862, now a lieutenant colonel, Littlefield was aboard the 183-foot steamer Eugene when it collided with the sunken wreck of an old steamer near Plum Point, Tennessee, punching a hole it is hull. Frantic passengers accidentally shoved the Shiloh veteran over the steamer’s railing. He floated downriver by hanging onto a stage plank until he was rescued by Union soldiers stationed at Fort Pillow.[3]

After serving for a time as the assistant provost marshal at Memphis, Tennessee, Littlefield was assigned to South Carolina in March 1863. He carried with him a letter of introduction from John G. Nicolay, President Lincoln’s private secretary, addressed to Major General David Hunter, stating that both Lincoln and Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton had “great confidence in his ability and energy” to lead a regiment of colored troops and to assist in organizing African-American troops. Shortly after being assigned to Hunter, Littlefield took command of the 21st U.S. Colored Infantry as a colonel. Following the failed assault on Fort Wagner in July 1863, which he took part as a member of Brigadier General Quincy A. Gillmore’s staff, he temporarily led the remnants of the famed 54th Massachusetts Infantry in place of Colonel Robert G. Shaw. Littlefield held various commands, including examining applicants of commissions in colored regiments, for the remainder of the war.[4]

Those who had met Littlefield were impressed with his soldiery qualities, skill as an orator, and passion for the Union cause. “The Colonel is yet a young man, and that unflinching perseverance, united with that perfect moral integrity that have so far elevated him,” a chaplain in the 21st U.S. Colored Infantry wrote in 1865, “will soon raise him to higher dignities and honors.” He had done well for himself during the war, rising from a captain to brevet brigadier general. It only seemed natural that he would continue on this upward trajectory in the postwar years. On the contrary, he plunged himself into a world of robbery and deceit which ended in ignominy.[5]

From War Hero to Fugitive

It is hard to pinpoint what turned this esteemed officer to a life of crime. Regardless of the cause, Littlefield saw the postwar South as ripe for exploitation and wrought havoc on it.[6]

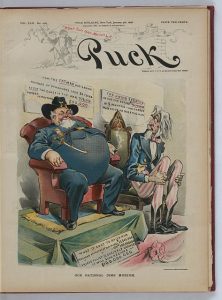

In 1867, he relocated to North Carolina where he began a partnership with George W. Swepson, president of the Western North Carolina Railroad. Newspapers estimated that the two swindled the state out of between $4,000,000 to $7,000,000 by buying and selling devalued railroad bonds and leaving behind many miles of unfinished railroad track. One newspaper reported their deed to be “one of the most notable events of the profligate and criminal era of carpet-baggery.” Ten years after his crimes, Littlefield was indicted by a grand jury in Wake County, North Carolina. The governor of North Carolina placed a $10,000 reward on his head, and despite multiple attempts to extradite him to the state from Florida to stand trial, the corrupt general evaded imprisonment.[7]

Even though he embezzled millions of dollars from his North Carolina railroad scheme, Littlefield ended up broke. In July 1888, he was arrested in New York for passing a worthless check for a meager $25. He was arrested for grand larceny in 1892, conspiring with Dr. Walter M. Fleming to accept bribes totaling $5,000 from Ms. Josephine Stephani in exchange for falsely testifying that her son, Alonzo, indicted for the murder, was insane. Littlefield was held for a $7,500 bail but ended up being acquitted. Soon after his release, he was arrested a third time for misappropriating a mortgage bond valued at $1,700 of the Sedgwick Loan and Investment Company. The onetime exalted Civil War officer’s depravity knew no bounds.[8]

General Littlefield suffered for years after the war from chronic diarrhea, which he attributed to “improper food, bad hygiene, and exposure” while serving as a soldier. On the evening of March 6, 1899, he consulted his physician complaining of symptoms of indigestion, constipation, and general debility. The next morning, his son contacted the doctor telling him that his father was suffering from unbearable bowel pains. Before the physician could arrive that afternoon, Littlefield experienced a “severe attack of vomiting and straining at stool, which resulted in the rupture of a cerebral artery,” leading to his death from cerebral apoplexy that same day. The Committee on Pensions, quite reluctant to provide pensions to Civil War veterans who didn’t have conclusive evidence that a disability or ailment was caused by wartime service, readily granted his widow, Anna, a pension of $30 a month following his death.[9]

Littlefield’s son, Milton, Jr., later a minister and author, was ashamed of the reputation his father had acquired after the war and was determined to erase any record of his misdeeds. “My father told me,” Milton Littlefield’s granddaughter wrote, “that he never addressed an audience (which he did many times all over the U.S.A.) that he didn’t have a dreadful fear that someone would recognize him or identify him as the son of M.S.L., Sr.” Following his father’s death, Milton, Jr. tore out all the pages from his father’s scrapbook. But removing a paper trail could not reverse the damage already done.

It is unclear if Littlefield’s grave was marked at the time of his death, or if his family intended for it to remain anonymous to keep it hidden from his many enemies. No tombstone was present at least in 1958 when Daniels published his biography on the controversial general. “Perhaps,” Daniels wrote, “such a symbol deserves the forgetfulness in crowded history which Milton Littlefield has received in his unmarked grave in much-monumented Kensico Cemetery near New York.” Ironically, his fellow thief-in-arms in North Carolina, George W. Swepson, has an impressive granite obelisk erected in the Tar Heel State.[10]

Honoring Littlefield

I began to wonder if I was doing the right thing by initiating a request for a government marker from the National Cemetery Administration (NCA) to honor Littlefield’s war service. Would it be improper due to his postwar depravity? Or is all that matters is his wartime service, not his misdeeds afterward? The more I began to ponder about General Littlefield, the harder this question became to answer. That was at least until I stripped back my sentiment and got to the heart of what I’m trying to accomplish with Shrouded Veterans.

I attended a presentation held about a month ago by Rex Melius of Cemeterians which helped me to decide how to proceed. Rex’s organization restored over 600 tombstones in Wisconsin’s Washington Country last year. The cemetery expert said something during his presentation that provided me with some clarity. He revealed to the audience that when he restores a tombstone, he tries to avoid allowing his sentiments to intervene in what he is trying to accomplish. His main concern is to clean and restore tombstones, not to judge the people buried underneath them.

Everything became much clearer for me from that point forward. My mission should be to memorialize soldiers that aren’t being recognized for their war service. Plain and simple. In the case of Littlefield and other veterans with tarnished legacies, I will leave it in God’s hand to judge them for how they chose to live their lives.

There’s no doubt that Brevet Brig. Gen. Milton S. Littlefield won’t be the last unmarked grave of a veteran with a checkered past I’ll encounter. At least next time I will spend less time mulling over if requesting a veteran marker is the right thing to do and instead focus on making sure the soldier gets the recognition he deserves for his military service.

Do you think I’m making the right call by proceeding with a request for a marker? Let me know in the comments section below.

Endnotes

[1] Jonathan Daniels, Prince of Carpetbaggers (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott Company, 1958), 28, 32-34, 38-41; John W. Vinson, “Personal Reminiscences of Mr. Lincoln,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society 8 (January 1916): 574-78.

[2] Author Johnathan Daniels claimed that at Shiloh, Littlefield “behaved with gallantry which no charges of misdeeds afterward could ever erase.” See Daniels, Prince of Carpetbaggers, 52-53; The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Series I, Volume X, In Two Parts. Part I—Records (Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1884), 223-25.

[3] Daniels, Prince of Carpetbaggers, 67-69; W. Craig Gaines, Encyclopedia of Civil War Shipwrecks (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2008), 94; “Steamer Eugene Wrecked,” The Daily Gate City (Keokuk, Iowa), November 20, 1862; “Terrible Steamboat Disaster,” The Weekly Pioneer and Democrat (Saint Paul, Minnesota), November 28, 1862; “The Loss of the Eugene,” Memphis Daily Appeal (Memphis, Tennessee), November 19, 1862.

[4] Daniels, Prince of Carpetbaggers, 59, 75, 80; “Special Order—No. 180,” Daily Union Appeal (Memphis, Tennessee), August 28, 1862; “The Attack of Fort Wagner—A Bloody Night Assault and Repulse,” The Spirit of Democracy (Woodsfield, Ohio), August 12, 1863; “Morris Island Items,” The Free South (Beaufort, South Carolina), August 15, 1863; “A Brave Negro Soldier—The Flag at Fort Wagner,” The Union (Georgetown, Delaware), November 27, 1863.

[5] Daniels, Prince of Carpetbaggers, 100.

[6] Littlefield may have demonstrated early signs of mischief during the war. See “Narrative of Mr. John H. Whelan,” American Citizen (Canton, Mississippi), October 3, 1862; Daniels, Prince of Carpetbaggers, 101-105.

[7] “A Reminiscence of Carpet-Baggery,” The New Orleans Daily Democrat (New Orleans, Louisiana), May 31, 1879; Knoxville Daily Chronicle (Knoxville, Tennessee), December 4, 1878; “Littlefield Discharged,” The Charlotte Democrat (Charlotte, North Carolina), June 6, 1879; “Littlefield,” The Farmer and Mechanic (Raleigh, North Carolina), June 5, 1879; “Milton S. Littlefield,” The Charlotte Democrat (Charlotte, North Carolina), February 27, 1872; The Bolivar Bulletin (Bolivar, Tennessee), February 11, 1871; John P. Arthur, Western North Carolina: A History (1730-1913) (Raleigh: Edward & Broughton Printing Company, 1914), 457-68; William L. Richter, The A to Z of the Civil War and Reconstruction, No. 37 (Lanham, MD: The Scarecrow Press, Inc., 2009), 362; Stephanie Murphy-Lupo, All Aboard! A History of Florida’s Railroads (Guilford, CT: Globe Pequot Press, 2016), 74-77; Michael Les Benedict, The Fruits of Victory: Alternatives in Restoring the Union, 1865-1877 (Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 1986), 43; A Journal of the Proceedings of the Assembly of the State of Florida at Its Fifth Session: Begun and Held in the Capitol, in the City of Tallahassee, on Tuesday, January 2, 1872 (Tallahassee: Charles H. Walton, State Printers, 1872), 335; “The Reconstructed Governors,” The Daily Phoenix (Columbia, South Carolina), February 29, 1872; “Whose is Governor,” The Weekly Caucasian (Lexington, Missouri), July 1, 1871; The Progressive Farmer (Winston, North Carolina), July 24, 1888; Charlotte Home and Democrat (Charlotte, North Carolina), March 12, 1886.

[8] The Progressive Farmer (Winston, North Carolina), July 24, 1888; Charlotte Home and Democrat (Charlotte, North Carolina), March 12, 1886; “Alleged Grand Larceny,” The Morning Call (San Francisco, California), October 14, 1890; “An Insanity Expert Arrested on a Grave Charge,” The Portland Daily Press (Portland, Maine), October 14, 1890; Santa Fe Daily New Mexican (Santa Fe, New Mexico), March 11, 1892; Asheville Daily Citizen (Asheville, North Carolina), February 13, 1892; Orange County Observer (Hillsborough, North Carolina), April 2, 1892; “General Littlefield Acquitted in One Case, Admitted to Bail in Another,” The State Chronicle (Raleigh, North Carolina), March 25, 1892.

[9] “Anna E. Littlefield Pension, Report No. 2042,” in The Reports of the Committees of the House of Representatives Made During the Second Session Fifty-Sixth Congress (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1900), 1-2.

[10] Daniels, Prince of Carpetbaggers, 21-22.

General Littlefield served with honor and distinction and deserves to have a VA marker on his grave. While his post-war life was deplorable, it should not have a negative impact on his service to his country.

Definitely the right thing to do. If you start judging, who makes the criteria of what is deplorable ? The marker is for his veteran service, not his moral standing.

I agree with placing the memorial, but as a wider question it might be worthwhile re-examining the post-war era. I guess it was a common opinion of radical republicans that the south deserved to be punished for the sin of slavery so Littlefield might have been putting into practice what others thought appropriate. Too after the reconciliation narrative took hold views of punishing the south would be considered outside the narrative and the views or claims of the NC state government might have been given more authority than warranted by the evidence. Then again the post-war period has been noted for irregularities and illegalities with railroad bonds (or bonded indebtedness in general) so Littlefield needs to be viewed in that context (and the history of railroad bonds and associated scandals and financial panics as well might be ripe for re-visiting).

I second all comments. A useful comparison case, and/or precedent, for you to consider is David Curtiss (D.C.) Stephenson.

His military service deserves the marker.

I’m in the same grey area on an identical situation.

Anthony Bowman, well said. Get the man his marker. Picking and choosing who is worthy enough to be honored for their military service is a rabbit hole best not ventured down. I could see it if he had been a bounty jumper, deserted before seeing battle or had been a documented coward or shirker, but this man served his time admirably.

As assistant provost marshal at Memphis in the spring of 1863, Littlefield then reported to Lieutenant Colonel Melancthon Smith of the Forty-fifth Illinois Infantry who was the provost marshal for Memphis up to mid-June. Smith requested to rejoin the regiment and arrived in Vicksburg just before June 25th and the regiment leading the attack against Fort Hill after the mine they help dig/lay was exploded. Within minutes of lead companies entering the crater of what was the fort, Smith was hit by 3 bullets, with one a mortal wound lodged in his brain. He was conscious and pain free for 3 days, dying on June 28. The merchants of Memphis came down to petition General Grant for Smith to be returned to his position in Memphis and Grant agreed, but Smith got a reprieve until after the attack. Tom