Visiting Grant Sites in St. Louis

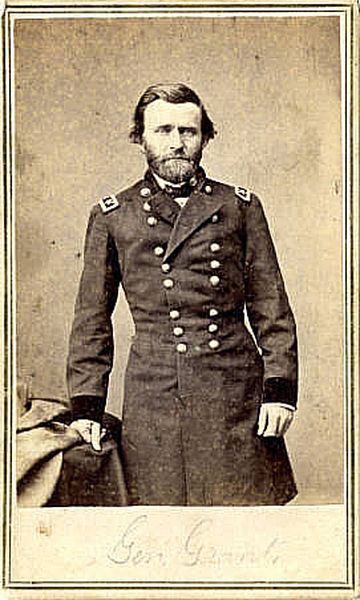

While watching the premiere episode of History’s Grant miniseries, I could not help but smile as I saw the various places President and General Ulysses Grant visited or lived in my hometown of St. Louis. As I grew up, Grant was everywhere I looked: Grant’s Farm, Ulysses S. Grant National Historic Site, Jefferson Barracks, and more. These sites were not simply places that Grant had stepped foot into for a mere moment, they were places that built and shaped the man who would play a crucial role in preserving the Union. Remarkably, many of these places can be visited today.

Perhaps the first place to visit would be Jefferson Barracks, the first military post Grant was stationed after his graduation from the United States Military Academy at West Point. Commissioned a second lieutenant with the 4th Infantry Regiment, Grant served at Jefferson Barracks from September 1843 until May 1844.[1] Though still an active military installation, you can still view the parade ground where he and over 220 other future Civil War generals performed drill on. Many of the original buildings from Grant’s time are gone, but you can visit the 1850s-era Laborer’s House, Ordnance Stable, Powder Magazine, and Ordnance Room. In some of these historic buildings is the Jefferson Barracks County Park museum, which features rotating exhibits about the history of the military post. Facing the parade ground in the 1905 Post Exchange and Gymnasium Building is the Missouri Civil War Museum. The museum houses thousands of artifacts and numerous exhibits about the Civil War in Missouri, as well as an exhibit gallery on the history of Jefferson Barracks.

While he was stationed at Jefferson Barracks, Grant formally met Julia Dent, daughter of Frederick Dent and sister of fellow West Pointer Fred Dent, at White Haven. Today, portions of the White Haven – including the home itself – are preserved by the National Park Service (officially named Ulysses S. Grant National Historic Site). There are museum exhibits and a film that showcase the history of White Haven and the life of Grant. You can also take a guided tour of the home with one of the park’s fantastic rangers.

Adjacent to Ulysses S. Grant National Historic Site is Grant’s Farm, an animal reserve located on property once owned by the Dents and Grant himself. In fact, it is a part of the 80 acres Frederick Dent gave to his daughter and son-in-law as a wedding present. While you can visit the farm for its animals and beer garden, the most remarkable aspect is seeing Hardscrabble. Hardscrabble was the log cabin home Grant built by hand for his growing family from 1854-1859. However, according to Grant’s Farm, the cabin is not in its original location. Park Ranger and Grant historian Nick Sacco wrote an excellent article about this history of Hardscrabble. Sadly, you cannot go inside Hardscrabble, but you can see it from a distance on the road adjacent to the park grounds or as you ride along the farm’s tram.

A final site in St. Louis related to Grant is the St. Louis Courthouse, or the “Old Courthouse,” as St. Louisans refer to it. Operated by the National Park Service’s Gateway National Park, you can walk inside and visit its many exhibits. Grant was here in 1859 when he freed William Jones, an enslaved man he had previously acquired from his father-in-law. [2] In American history, the Old Courthouse is most notable for being the site where Dred Scott first sued for his freedom in 1846.

Next time you visit St. Louis, Missouri, make sure you take some time to visit these various Grant sites. To understand Grant during the Civil War to the White House and beyond, you must understand Grant in these formative years. These years in St. Louis, where he was first stationed as a young Army officer, where he met and married his wife, where he built his first home, and where he freed his first enslaved man, helped shape this influential American.

Sources:

- Marc E. Kollbaum, They Served at Jefferson Barracks (2018), 1.

- Nick Sacco, “The Mystery of William Jones,” Journal of the Civil War Era, December 7, 2018, https://www.journalofthecivilwarera.org/2018/12/the-mystery-of-william-jones-an-enslaved-man-owned-by-ulysses-s-grant/?fbclid=IwAR2vKD6Zel7NQXIPlioZijEesLKovDrny1XvkEi0RXjooYMjl5HLw3rY5gU.

I too was born & raised in St. Louis, and recall a field trip to Grant’s Farm in the ’60s. I recall being told that the vertical fails in the fencing around the property was made from rifle barrels of surplus muskets after the war. Your post here has made me go and try and confirm that…

Thanks for reading! I’ve read that the fence was built with 2,500 rifle barrels by August Busch, Jr., to honor Civil War veterans.

when were the cannons placed by Hardscrabble?

timm

Thanks for reading, Timm! Not sure about when they were placed. I will let you know if I can find the answer.

So many political and military leaders of the War have connections to Missouri. We too often get overlooked. (The Grant miniseries stole our Battle of Belmont & moved it to Kentucky.). Our town of Mexico, MO is on the US Grant Trail and hosted the US Grant Symposium in 2018. I attended the one in St. Louis in 2019 which featured Dr. Timothy Smith, one of the historians in the Grant miniseries.

Hi Tony! Thanks for reading and commenting. You are so right about all the connections to Missouri. The more we share the history of Missouri during the Civil War, the more it can garner interest.

It really was a bummer to see Belmont being placed at Kentucky rather than Missouri in the miniseries. I just hope people take the time to read more about Belmont and realize it was in Missouri.

Most branches of my family tree were in Missouri by the 1850’s. Mostly Union, and some Confederate. At the Battle of Byram’s Ford (part of the larger Westport battle) at least 6 fought – 3 on each side, directly against each other. All 6 survived the War, but with both physical & mental wounds. All from the same small community in the Ozarks in Wright County.

Great post! I didn’t realize Hardscrabble was still standing.

Thanks, Chris! Glad you enjoyed it.