“The 18th Connecticut was now the only regiment left on the field” Second Lieutenant Asahel George Scranton

ECW welcomes guest author Steven Stabler

The Battle of Second Winchester fought June 13-15, 1863 saw Lieutenant General Richard S. Ewell’s 12,500 Confederates face off against Major General Robert H. Milroy’s force of 7,000 Union troops tasked with defending the Shenandoah Valley. Among Milroy’s defenders was the 18th Connecticut Infantry and Asahel George Scranton, a second lieutenant serving within Company K. Notably, the 18th Connecticut never saw combat prior to Second Winchester; therefore, their tale provides firsthand recollections of battle and the conditions faced by Union prisoners of war from a unique perspective. This is their story.

Asahel George Scranton was born on May 18, 1833 in the town of Killingly Connecticut to unknown parents. Little is known about Scranton’s early life other than he received some form of education and was able to read and write.[1] Prior to the war Scranton worked as a painter and eventually married a woman named Elizabeth.[2] Asahel and Elizabeth had two children, a daughter Fanny Maria in 1859, and a son Samuel W. in 1862.[3] On August 5, 1862 Scranton enlisted in the Union Army as a 1st Sergeant. Thirteen days later at Harpers Ferry, West Virginia he mustered into Company K. of the 18th Connecticut Infantry under the command of Colonel William Grosvenor Ely[4]— it was also during this time that Scranton was given an officer’s commission as a second lieutenant.[5]

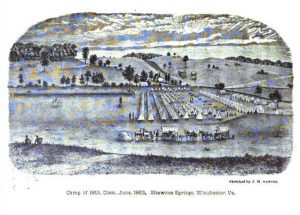

Likewise, the 18th Connecticut registered into U.S. service on August 18, 1862. May 22 of the following year they received orders to report to General Milroy in Winchester, Virginia. From their post in Baltimore, Maryland the 18th Connecticut rode by train to Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, then marched to Winchester, arriving on the afternoon of May 25. After a brief rest in the city, the regiment marched south to fortify Shawnee Springs or “Camp Shawnee”. Here the 18th Connecticut dug earthworks and rifle pits, established pickets and patrolled the surrounding area including the famous “Star Fort” on Front Royal Pike— all the while, target practice, drill sessions, and foraging missions were common.

Finally, on the morning of June 13, 1863 Union scouts reported Ewell’s Confederates were “coming down the valley in force.”[6] Scrambling to face the enemy, the 18th Connecticut came under musket and cannon fire at Front Royal Pike. Despite their inexperience, the 18th Connecticut held firm until they were ordered to abandon their positions around Camp Shawnee and reform with Union contingents outside of Winchester City. As the battle raged on, Corporal Charles Lynch noted the 18th Connecticut was under fire all day and explained they could “see gray in all directions.”[7] Outnumbered, the regiment participated on the first day in a deadly game of cat and mouse, as the regiment was forced to maneuver several times to meet the enemy and avoid being flanked. By nightfall, the 18th Connecticut’s position had shifted to east of Winchester as the regiment settled along the Berryville road. At night the men were exposed to the elements and endured lightning and thunderstorms.[8]

After a restless night, the 18th Connecticut were ordered to move their lines north and capture a large brick house occupied by Confederate sharpshooters who were “making the line hot.”[9] After a successful charge alongside the 5th Maryland, they cleared the house and took a few prisoners. The house was later reoccupied by the rebels, then promptly obliterated by friendly artillery. This small victory boosted morale. However, General Ewell’s troops continued to tighten their grip around Winchester. Understanding the situation, General Milroy consolidated his defense around Star Fort in a final effort to hold the city. Throughout the second day both sides fought vigorously, with cannon and rifle echoing throughout the Valley. Milroy’s troops were able to hold until night, but not without consequence. Surrounded and without support, the Union situation was dire. Milroy had two options, to fight his way out of Winchester, or surrender entirely to Ewell. After holding a formal council of war with his staff, Milroy opted to fight through Ewell’s encirclement. Under the cover of darkness, the Union troops occupying Star Fort lowered the colors, spiked the canons, and prepared to evacuate. Meanwhile, the now battle hardened 18th Connecticut and 5th Maryland quietly marched from Star Fort to the Martinsburg Pike to secure an escape route.

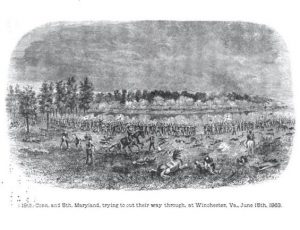

On the dawn of June 15, the Union garrison was ordered to evacuate from Winchester. It was here the 18th Connecticut would make a daring delaying maneuver to allow General Milroy and the remainder of the Union Army to retreat from Winchester. Under immense fire with little support, the 18th Connecticut made three repeated charges through a plot of woods and across the Berryville Pike against Snowden Andrews’ Baltimore Flying Artillery positioned on a bridge spanning the railroad cut at Stephenson’s Depot. The first charge was supplemented by the 5th Maryland and repulsed; however, this action bought valuable time.

By the second charge the remainder of the Union force at Winchester was in full retreat as “The 18th Connecticut was now the only regiment left on the field with General Milroy.”[10] The final charge was determined and successfully took out the artillery battery whilst holding “the enemy in check until the General, his staff, and escort, left the field…”[11] After the third charge the 18th Connecticut was overwhelmed and attempted to flee. During the frantic rout “Between four hundred and five hundred were made prisoners… and between two hundred and three hundred got away.”[12]

The 18th Connecticut’s final stand marked the end of the battle. The Union defeat at Winchester led to Milroy’s force abandoning the Shenandoah Valley, thus opening the corridor to the north and beginning the subsequent invasions of West Virginia, Maryland, and Pennsylvania by the Confederacy. Among the captured was Lt. Scranton, who was sent to the city of Macon Georgia.[13] The conditions in the prison were poor, as rations consisted of, “A very small, poor piece of bacon and a similarly small allowance of corn meal,” he wrote.[14]

By November 1864, conditions continued to deteriorate when Major General William Tecumseh Sherman’s “March to the Sea” approached Macon. As Sherman pressed on, more captured Union troops, including the sick and wounded, began to fill the prison. Agony and disease became rampant, causing Scranton and others to fall ill. When Sherman drew close to Macon, the Confederates guarding the prison were ordered to evacuate— bringing with them the fit and able, while leaving behind the sick and injured. Scranton vowed to stay behind and tend to his comrades. By the time Sherman’s Army liberated the prison, almost a year passed before Scranton and twelve other officers[15] were paroled on December 10th, 1864[16] and released back to Union lines.

There was great interest in the officers’ return, soon followed by an internal debate about the 18th Connecticut’s actions at Second Winchester. Amidst the quarrelling, Scranton sought to keep the men together, as he wrote a letter “calling attention to the fact that Capt. Matthewson, of the same company, deserved the highest praise for leading his company in three charges in the face of the greatest danger.”[17]

Scranton’s devotion to his men as both a prisoner of war and an officer as shown by this gesture bonded all of Company K. through the rest of the war. The men later heard of Milroy’s praising of the regiment’s performance during the battle, having gone on record to say: “If I had ten regiments like the Eighteenth Connecticut, I would whip the rebels out of their boots before sunset.”[18] From here, any sense of doubt turned into a sense of pride that the regiment carried wherever they went.

As for Scranton, he remained with Company K. until the 18th Connecticut mustered out on June 27th, 1865.[19] After the war Scranton returned home to his family and made a decent living as a house and sign painter.[20] Asahel G. Scranton died on Nov 7, 1900, and is buried at Westfield Cemetery in Danielson, Windham County, Connecticut, USA.[21]

[1] “Asahel G. Scranton – Find a Grave Memorial,” Find a Grave.com, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/37623393

[2] “A G Scranton in the 1860 United States Federal Census,” Ancestry.com, https://search.ancestry.com/cgi-bin/sse.dll?db=1860usfedcenancestry&indiv=try&h=17602188.

[3] “A G Scranton in the 1870 United States Federal Census,” Ancestry.com,

https://search.ancestry.com/cgi-bin/sse.dll?dbid=7163&h=13573401&indiv=try&o_vc=Record:OtherRecord&rhSource=60525

[4] William Carey Walker, History of the Eighteenth Regiment Conn. Volunteers in the War

for the Union. (Norwich, Connecticut: Norwich committee, 1885), 431.

[5] Connecticut, “Record of service of Connecticut men in the army and navy of the United States during the War of the Rebellion.” HaithiTrust Digital Library, 687. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.d0000140178&view=1up&seq=707&size=150

[6] Charles H. Lynch, The Civil War Diary, 1862-1865, of Charles H. Lynch 18th Conn. Vol’s.

(N/A: Harvard University Library, 1915), 19.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid, 21.

[11] Ibid, 21-22.

[12] Ibid, 22.

[13] Connecticut, “Record of service of Connecticut men,” HaithiTrust Digital Library, 687. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.d0000140178&view=1up&seq=707&size=150

[14] William Carey Walker, History of the Eighteenth Regiment Conn.,

(Norwich, Connecticut: Norwich committee, 1885), 363.

[15] William Carey Walker, History of the Eighteenth Regiment Conn.,

(Norwich, Connecticut: Norwich committee, 1885), 329.

[16] Connecticut, “Record of service of Connecticut men,” HaithiTrust Digital Library, 687. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.d0000140178&view=1up&seq=707&size=150

[17] Ibid, 187.

[18] Ibid, 109.

[19] Connecticut, “Record of service of Connecticut men,” HaithiTrust Digital Library, 687. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.d0000140178&view=1up&seq=707&size=150

[20] “A G Scranton in the 1870 United States Federal Census,” Ancestry.com, https://search.ancestry.com/cgi-

[21] “Asahel G. Scranton – Find a Grave Memorial,” Find a Grave.com, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/37623393

Steven P. Stabler is a McCormick Civil War Institute work-study pursuing undergraduate degrees in history and political science, minors in writing and global studies, and certifications in Civil War Era Studies and Public History at Shenandoah University.

Hello Steven Stabler, it’s human interest reports such as this excellent one, which make me a fan of this blog. Good wishes. Hope more such ones will follow.

Steven Stabler. Message me. I have some interesting info on one relative Major Ephraim Keech Jr a blacksmith from Danielson who trained the 18th for a year and a half prior to the 2nd Battle of Winchester and his brother (my gggrandfather) who escaped the battle then joined the renowned 1st Ct Calvary for two years until the end of the war. Darin Keech 860-287-7956

Magnificent writing !

/Users/darin/Desktop/78165574_1117817501930220_949294077151543296_n.jpg

Major Ephraim Keech Jr. 18th Regiment

I hope the photo came out here.