“I Think, Boys, I am Done For!”: A Prussian General in Union Blue Endures Trying Times in Georgia

ECW welcomes back guest author David T. Dixon

August Willich heard the commotion and leapt onto his horse, desperate to rejoin his command.[1] Amid the smoke and confusion, he galloped directly into McNair’s Arkansans, who were mopping up what was left of Kirk’s broken brigade. James Stone, a volunteer aide to General McNair, confronted Willich and demanded his surrender, but Willich turned his horse and fled.[2] A cannonball shattered the hind leg of Willich’s horse, but the general was uninjured. Stone took Willich’s sword and led him away.[3]

Willich and thousands of captured Union soldiers were rushed to the rear of the Confederate lines. Jubilant guards herded the captives into the walled courthouse yard in Murfreesboro. A fellow prisoner observed Willich wringing his hands and moaning, “My poor boys! My poor boys!”[4] His brigade decimated, Willich and his comrades were forced to sign a parole of honor, promising not to fight the Confederates until exchanged.

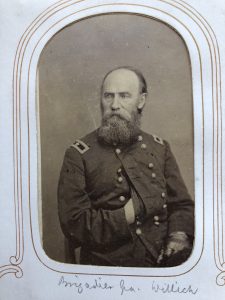

August Willich was the prize capture for Confederates at the Battle of Stones River which ushered in January 1863. A career officer in the Prussian army, he had joined ill-fated rebellions in Germany in 1848 and 1849 against his king. He then became a political refugee in America.

In the opening year of the American Civil War, Willich rose rapidly in the volunteer Union army, commanding a regiment that defeated a much larger force of Confederates at Rowlett’s Station, Kentucky. Willich’s sparkling performance at Shiloh in April 1862 earned him promotion to the rank of general, commanding what became the First Brigade in the Second Division of the right wing of Rosecrans’s army.

Now a prisoner, Willich gazed out of Murfreesboro’s courthouse window at smoke from the battle two miles to the northwest. His ears told him that the initial rout had turned into a desperate struggle. His eyes convinced him that reports from rebels of Rosecrans in full retreat toward Nashville were false. A deluge of prisoners into the courthouse yard slowed to a mere trickle.

Near nightfall, cannon still thundered. Willich and his famished, exhausted comrades marched to the rail station, loaded into boxcars, and began their journey south. The prisoners received only water until they reached Chattanooga late in the evening of January 1, 1863. They were shuttled to a warehouse on the outskirts of town, then back to the cars for a night ride to Atlanta. By early morning, Willich and his companions reached Atlanta for what most figured would be a short stay. It turned out to be several weeks.

The captives’ place of confinement, a fine three-story brick building at the corner of Whitehall and Alabama streets, looked clean and spacious at first glance. The building had been the local Masonic Hall until 1860. Merchants Brown and Fleming occupied the bottom two floors. The third floor, where the prisoners were housed, looked filthy and deserted. In fact, it was crowded with new neighbors who would make their days unbearable and their nights devoid of slumber. The makeshift prison was infested with lice.

Willich’s fair, thin skin made him a particularly sweet treat for the ravenous insects. The fifty-two-year-old general was so pestered by his unwelcome bedmates that he thought they, rather than the rebel army, would end his time on earth. He procured large quantities of mercurial ointment, which made him gravely ill and did little to alleviate his suffering. After a hospital stay of several days, an emaciated Willich returned to his friends complaining, “If I stay here, the little vermin will kill me. If I use medicine, the medicine kills me. So, I think boys,” he whimpered, “I am done for.”

Life in the prison was not all pain and drudgery. Captives enjoyed an unlimited supply of gas for the chandeliers, using its bright light to enliven cheery “stag dances” and other amusements. General Willich gave lectures on military tactics. Another officer recited Shakespeare. A third led the prisoners in exercise routines. Inmates enjoyed chess, checkers and cards.

Prisoners had begun arriving in Atlanta in significant numbers during the spring and summer of 1862, following the horrific battle at Shiloh Church, in Tennessee. Atlanta’s secret circle of Union supporters did whatever they could do safely to help Federal prisoners as they passed through town. Local Union men, women, and even children took great risks to assist captive Union soldiers by placing money in newspapers, books, and pies on clandestine visits to rail cars and prisons. One Atlanta newspaper reported with frustration that “respectable” ladies of the community brought bouquets of flowers and strawberries to the Yankee prisoners.[5]

Rations supplied to the prisoners were barely enough to keep them alive. Once a day, an enslaved man entered the prison with a small supply of boiled beef and cornbread. “Here’s your meat, here’s your cornbread,” he exclaimed. Most parolees were allowed to keep money and personal possessions, creating a thriving underground economy in edible contraband. Greenbacks were worth twice their face value in Confederate currency, so captives traded their cash for sweet potatoes, onions, and butter. They concocted a tasty stew, combining these items with meat, cooked together in an oyster can in one of three small fireplaces, using green pine logs as fuel. One or two prisoners at a time were allowed to shop at the market, accompanied by a guard.[6]

On February 25, a Confederate officer entered the building with welcome news. Willich and his comrades would finally leave for Richmond to be exchanged. The prisoners were in good spirits as they scrambled into boxcars that evening and headed east.

Willich and the rest of the Union prisoners reached Augusta the next day That evening, Willich found a German inn and enjoyed a brief respite from his troubles with “twelve merry German musicians and a German professor.”[7] The following day they hopped aboard passenger cars for the journey across South Carolina. Morale soared as they pulled into Richmond. Freedom appeared close at hand. Such hopes were dashed as the men marched to their new home, the infamous Libby Prison in Richmond, Virginia.[8] Willich endured several months of deprivation at Libby before his exchange in early May 1863. He returned to his command in time for the summer campaign.

Georgians had not seen the last of August Willich. He performed with typical skill and bravery in a losing effort at the Battle of Chickamauga, covering the retreat of Union forces back to Chattanooga.

In the opening weeks of Sherman’s Atlanta campaign, Willich found himself once again staring down rebels, this time during the Battle of Resaca. On the afternoon of May 15, 1864, the old general dismounted and climbed to the top of a parapet, field glasses in hand, to take stock of the stalemate.[9] A rebel sharpshooter less than two hundred yards away crouched low, took upward aim at his quarry, and pulled the trigger. A single ball ripped through Willich’s upper right arm near the shoulder, glancing off the bone and exiting his back below the shoulder blade, barely missing his spine.[10]

Willich would never fight again. The rebel ball that pierced his shoulder at Resaca had severed a nerve in his right arm, rendering that limb nearly useless for the rest of his life. [11] Despite successful campaigns throughout the West, August Willich would remember his Civil War experiences in Georgia as frustrating times marked by captivity, defeat, and disability.

David T. Dixon is the author of The Lost Gettysburg Address. His biography Radical Warrior: August Willich’s Journey from German Revolutionary to Union General will be published by The University of Tennessee Press in September, 2020.

Sources:

[1] Richard W. Johnson, A Soldier’s Reminiscences in Peace and War (Philadelphia: J.R. Lippincott, 1886), 212-3.

[2] Gustavus Kunkler to Rosalie Kunkler 9 Jan. 1863, Gustavus Kunkler Papers, Navarro College Archives, Corsicana, Texas.

[3] O.R., series 1, vol. 20, pt. 1, 912, 946-8. Madison (Indiana) Daily Evening Courier, 17 Jan. 1863.

[4] Alexis Cope, The Fifteenth Ohio Volunteers and Its Campaigns (Columbus, Ohio: Alexis Cope, 1916), 250.

[5] Thomas G. Dyer, Secret Yankees: The Union Circle in Confederate Atlanta (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1999), 82-96.

[6] Newlin, A history of the Seventy-third regiment of Illinois infantry, 564-7.

[7] Reinhart, ed., August Willich’s Gallant Dutchmen, 143.

[8] Newlin, A history of the Seventy-third regiment of Illinois infantry, 567.

[9] Cope, The Fifteenth Ohio Volunteers, 435.

[10] August Willich Pension File No. 77658, National Archives, Washington, D.C.

[11] Cope, The Fifteenth Ohio Volunteers, 435-6.

Very interesting post! Thank you…

Very entertaining. Thank you!

Thanks again for contributing time and effort to presenting the story of this fascinating man. One curious aspect of Willich, most of his fellow Germans/ Prussians, Hungarian veterans of the 1848/49 Revolution, Garibaldi’s Italians… Why did so many supporters of Revolution in Europe defend the Federal side AGAINST the Rebels in America?

Guess we’ll have to read your book to find out…

Cheers

Mike Maxwell

Great question Mike and yes it is a rather long and complex answer, especially considering that the rebels also took inspiration from these 48ers in that they felt it was their right to self-determination and to build a republic based on slavery. Therein lies the key. The overwhelming majority of the Europen 48ers were anti-slavery or even, like Willich, abolitionist. Willich saw chattel slavery and the abuses of wage laborers as emanating from the same place:an aristocratic ruling class that was inherently opposed to the rights of man and true Republican sympathies.

Thanks to David T Dixon. An engaging read which I shared on Facebook.

I had an ancestor Andrew Jackson Hillenburg (second generation German American, originally from Virginia) who was in Willich’s 32nd Indiana. The regiment was nicknamed the First German.

“Villich” lives. Can’t wait to get the book. Great article