An Iowa Soldier’s First Combat Experience at Wilson’s Creek

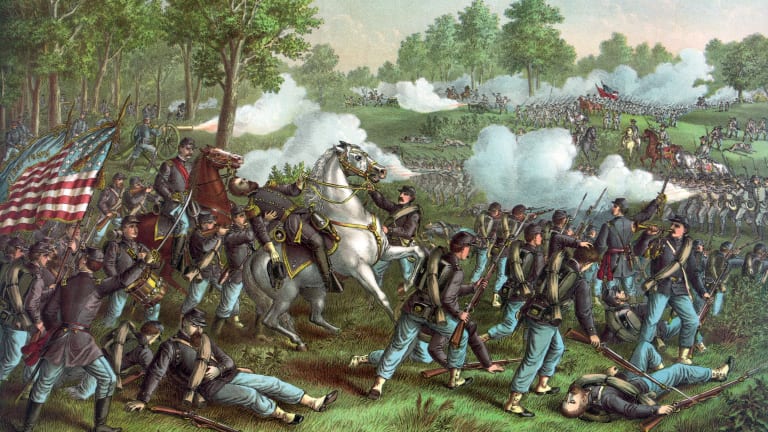

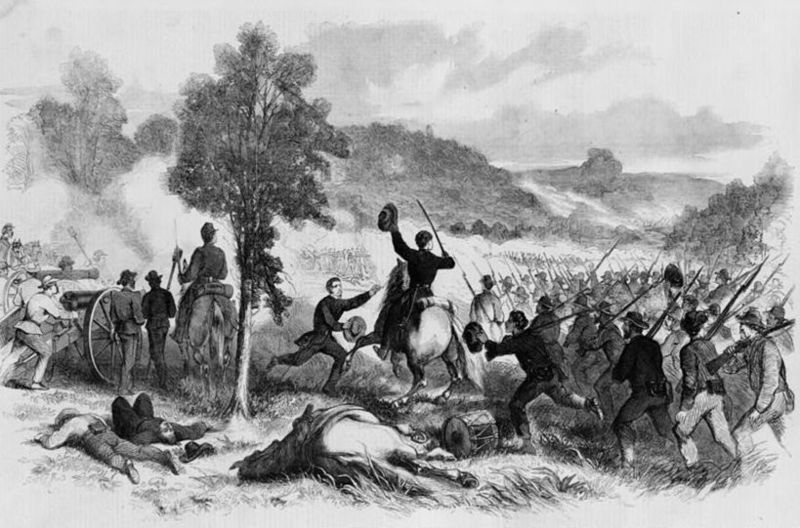

Today marks the 159th anniversary of the Battle of Wilson’s Creek, fought on August 10, 1861 along the banks of the Wilson Creek, a mere twelve miles to the southwest of Springfield, Missouri. One of the first major battles of the Civil War fought west of the Mississippi River, Wilson’s Creek was the culmination of a summer-long campaign over what many called, the “Fight for Missouri.”

Throughout the summer of 1861, Brig. Gen. Nathaniel Lyon’s troops maneuvered through central and southern Missouri, securing the Missouri River, the state capital at Jefferson City, and the vital Pacific Railroad line for the Federals. Maj. Gen. Sterling Price’s Missouri State Guard, a state defense force that was pro-secessionist, fell back toward the southwestern corner of the state, hoping to unite with Confederate forces under Brig. Gen. Ben McCulloch and ultimately defeat Lyon.

By August 9, Price and McCulloch’s “Western Army” were encamped in the Wilson Creek valley, planning to attack Lyon’s army at Springfield. However, due to storms, the Southern forces postponed their attack. Lyon, on the other hand, planned to attack at dawn with his outnumbered army. The element of surprise and a double envelopment strategy would hopefully even the numbers.

At dawn on August 10, exactly forty years after Missouri was admitted to the Union as the 24th state, Lyon’s forces opened fire on the Western Army. For hours, the fighting raged at places like Bloody Hill, the Ray Cornfield, and the Sharp Farm. Most men from Missouri, Kansas, Arkansas, Texas, and Iowa experienced their baptism of fire on these southwestern Missouri fields.

Pvt. Eugene Ware of Company E, First Iowa Infantry was one of those green soldiers who experienced full-fledged combat for the first time at Wilson’s Creek. In his 1907 memoir, The Lyon Campaign in Missouri, Ware described his own combat experience on Bloody Hill.

” When they got close the firing began on both sides. How long it lasted I do not know. It might have been an hour; it seemed like a week; it was probably twenty minutes. Every man was shooting as fast, on our side, as he could load, and yelling as loud as his breath would permit. Most were on the ground, some on one knee …”

“Corporal Bill received a minie ball on the crest of the forehead. The ball went over his head, tearing the scalp, sinking the skull at the point of impact about one-eight of an inch. He bled with a sickening profusion all over his face, neck, and clothing; and as if half-conscious and half-crazed, he wandered down the line, asking for me; he was my blanket-mate. He said, “Link, have you got any water in your canteen?” I handed him my canteen and sat him down by the side of a tree that stood near our line, but he got up and wandered around with that canteen, perfectly oblivious; going now in one direction and then in another. From that depression in the skull, wasted to a skeleton, he, an athlete, died shortly after his muster-out, with consumption. How could it be?”

“We heard yelling in the rear, and we saw a crowd of cavalry coming on a grand gallop, very disorderly, with the apex pointing steadily at out pieces of artillery. We were ordered to face about and step forward to meet them. We advanced down the hill toward them about forty yards to where our view was better, and rallied in round squads of fifteen or twenty men as we had been drilled to do, to repel a cavalry charge. We kept firing, and awaited their approach with fixed bayonets. Our firing was very deadly…The charge, so far as its force was concerned, was checked before it got within fifty yards of us.”

“After this last repulse the field was ours, and we sat down on the ground and began to tell the funny incidents that had happened. We looked after boys who were hurt, sent details off to fill the canteens, and we ate our dinners, saving what we did not want of our big crusts and hanging them over our shoulders again on our gun-slings. We regretted very much the death of General Lyon, but we felt sanguine over our success, and thought the war was about ended … The boys were highly pleased that they had got through with the day alive, and there was no idea that the day had gone against us.”

When the guns fell silent and the Federals determined to retreat back to Springfield, approximately 2,500 men had been killed, wounded, or missing. Lyon himself was killed, making him the first Union general to be killed in the war. Like many of the 90-day Federal volunteer units, the First Iowa was mustered out soon after on August 20. The Iowans had suffered greatly at Wilson’s Creek, losing 13 killed and 141 wounded.

Though it was a Confederate battlefield victory, McCulloch and his Confederates retired to Arkansas, leaving Price to follow up on his success on his own. That next month, Price was again successful, taking out the Union garrison at Lexington. However, he and his Missouri State Guard were unable to take advantage of these victories and were forced to retreat south. Instead, Federal forces took control of Jefferson City, placing a new provisional government in place, which remained in power the rest of the war. It was not until 1864 that Price attempted to capture the state for the Confederacy during his 1864 Missouri Expedition. Lyon’s small Federal Army of the West was not victorious at Wilson’s Creek, but his “fight for Missouri” had actually been a victory itself, as it set the stage for Federal control the rest of the war and beyond.

Always a joy to read something fresh about the First Iowa Volunteers, which had as its nucleus the Dubuque Governor’s Greys; and drew surplus numbers of men willing to sign on in April 1861 that the 2nd Iowa and 3rd Iowa were organized concurrently (though as three-year regiments.) The Battle of Wilson’s Creek was fought as the 90-day term of service was expiring; and after the 1st Iowa disbanded, many of the veterans joined new Iowa regiments then forming (the 7th Iowa, 12th Iowa and 14th Iowa in particular, all of which fought at Shiloh.) Eugene Ware (the featured author) joined an Iowa cavalry regiment.

Thanks for introducing this first-hand account of the First Iowa.

Hello Kristen

I wanted to see if you would consider giving our RMCWRT a presentation via Zoom?

We have some openings this fall. Could you please reach out to me at the email provided.

Regards

Don Hallstrom