A Tale of Two Fields: Where the 3rd Wisconsin’s Reconnaissance Fought at Cedar Mountain

ECW welcomes back guest author Chris Bryan

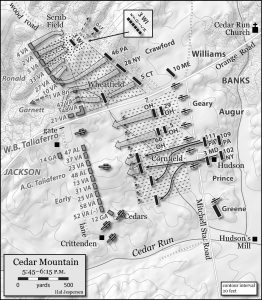

As a four-hour artillery duel raged on the sweltering afternoon of August 9, 1862, Union and Confederate infantry under Major Generals Nathaniel Banks and Thomas J. Jackson arrived on the fields north of Slaughter’s Mountain, eight miles south of Culpeper Court House, Virginia. The inchoate battle of Cedar Mountain occurred amidst two dominant features, a cornfield and a wheatfield, separated by the Orange-Culpeper road. This segment of the road travelled largely east-west. This study involves events north of the road where a brigade from each army held the woods on either side of the wheatfield when the battle started. North of these two brigades, in one of several uneven matchups that day, six companies of the 3rd Wisconsin fought the Stonewall Brigade; it went poorly for the Federals. Participants interpreted the location of this fight differently. This analysis considers the available primary evidence.

As a four-hour artillery duel raged on the sweltering afternoon of August 9, 1862, Union and Confederate infantry under Major Generals Nathaniel Banks and Thomas J. Jackson arrived on the fields north of Slaughter’s Mountain, eight miles south of Culpeper Court House, Virginia. The inchoate battle of Cedar Mountain occurred amidst two dominant features, a cornfield and a wheatfield, separated by the Orange-Culpeper road. This segment of the road travelled largely east-west. This study involves events north of the road where a brigade from each army held the woods on either side of the wheatfield when the battle started. North of these two brigades, in one of several uneven matchups that day, six companies of the 3rd Wisconsin fought the Stonewall Brigade; it went poorly for the Federals. Participants interpreted the location of this fight differently. This analysis considers the available primary evidence.

The recently harvested Wheatfield was approximately 600 yards north to south. Wheat stood in shocks about the field. Its width tapered from about 600 yards at the southern border with the road to about 200 yards wide at its northern border, which abutted a field covered in scrubby shoulder-height vegetation. A slight ridge separated the two fields. Both fields shared a fenced wood as an eastern boundary. The smaller, rectangular scrub field covered the entire northern border of the Wheatfield and continued west, with its length oriented east to west. Taken together, the two fields formed an inverted, reverse L-shape.[1]

Forty yards from the eastern wheatfield border, three Federal regiments of Brigadier General Samuel Wylie Crawford’s brigade waited. Across the wheatfield, approximately two regiments worth of Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Garnett’s brigade of Virginians faced Crawford’s men, while the rest of Garnett’s brigade faced the Cornfield to the south. The 10th Virginia from Brigadier General William B. Taliaferro’s brigade was en route through the woods behind Garnett, from south of the road, to take position on Garnett’s left. The Stonewall Brigade, under Colonel Charles A. Ronald, also slogged through undergrowth with orders to arrive on Garnett’s left. The Stonewall Brigade arrived at the western end of the scrub field shortly before Crawford’s regiments charged across the wheatfield against Garnett.[2]

Earlier, around noon, Brigadier General George H. Gordon’s Federal brigade deployed to a hillside far to the right, with 800-1000 yards and a marshy run between them and the position Crawford occupied before advancing toward the wheatfield. After arriving, Gordon directed Colonel Thomas Ruger, commanding the 3rd Wisconsin, to advance a detachment to scout for Confederates.[3]

Ruger led six companies across the run and into the woods to within 100 yards from the wheatfield astride an old wood road. The reconnaissance produced no contact. As the Badger Staters waited, the 46th Pennsylvania passed through their line, paused a few minutes, and then continued forward toward the wheatfield and out of sight. Crawford sent orders to join his advance. Ruger demurred. He was under Gordon’s orders and any change needed to come from a higher authority than Crawford. Soon, Captain Wilkins of division staff arrived, claiming orders from Banks. Colonel Ruger then marched toward the right far enough to achieve what he supposed was sufficient distance beyond the 46th Pennsylvania to uncover. He then called a halt for a short speech before pressing forward as close to double quick as possible over the difficult terrain and briar-filled undergrowth. Their path diverged from the 46th Pennsylvania on their left. When they emerged from the woods, the Pennsylvanians were out of sight, but Col. Ronald’s Virginians soon appeared. Into which field did these companies emerge and fight? Primary accounts conflict.[4]

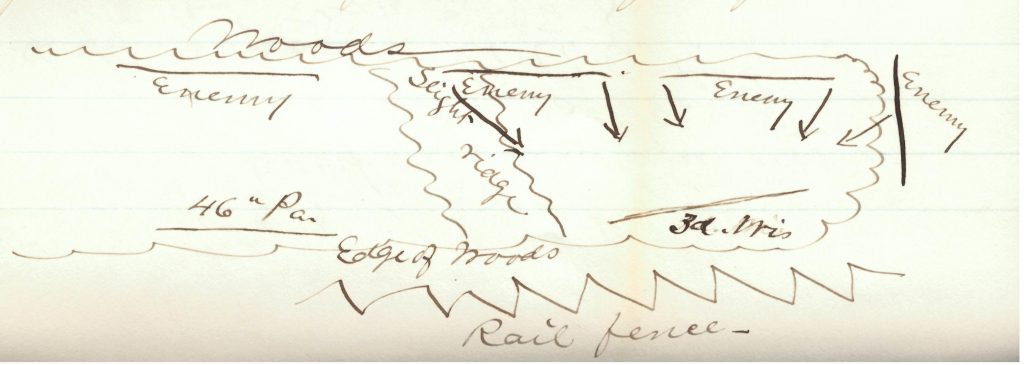

Julian Wisner Hinkley’s 1912 book seemingly placed the 3rd in the wheatfield, describing an “open field” as they emerged from the woods. Ruger’s official report indicated that his companies were “placed on the right of [Crawford’s] line.” These references from Hinkley and Ruger, taken with accounts from the Stonewall Brigade of a right wheel by its three left regiments onto the border with the wheatfield, strongly suggest that the Virginians executed this right wheel then enfiladed the 3rd Wisconsin. This is the generally accepted modern interpretation. However, primary sources other than those mentioned above suggest that the location of this action may have occurred within the scrub field.[5]

Edwin Bryant’s 1891 history of the 3rd Wisconsin placed it in the scrub field. Bryant’s account matched every official report from the Stonewall Brigade. This brigade, from left to right, was the 4th, 2nd, 5th, 33rd, and 27th Virginia regiments. From these reports, it is clear that the 4th Virginia, in the woods to the north, was the only regiment without Federals directly in their front. The 2nd and 5th Virginia reports described attacking Federals straight ahead across the scrub field, driving them back into the woods, before wheeling right to engage Federals in the wheatfield. The 27th and part of the 33rd were in the woods south of the scrub field and stopped when they reached the wheatfield. Bryant, clearly referencing the Confederate official reports, described the 2nd Virginia straight ahead of the 3rd Wisconsin, and the 4th and 5th firing on their right and left, respectively.[6]

In an 1895 National Tribune article, Hinkley described the action occurring within the “old bushy field.” Hinkley likely referenced Bryant’s history for this article. His account of the relative positions of the Stonewall Brigade’s regiments matches Bryant, going so far as to point to the 33rd and 27th Virginia engaging Crawford’s brigade in the wheatfield during the 3rd Wisconsin’s fight with the 5th, 2nd, and 4th Virginia. It is at first unclear what changed Hinkley’s mind between 1895 and his comparatively vague published account in 1912. However, Hinkley’s handwritten manuscript of the book in his personal papers provides more detail. First, he called it a “cleared field” rather than an “open field.” This could still point to the recently harvested wheatfield. But, additional details make clear that he meant the scrub field, which was a recently cleared woodland. Hinkley’s draft also mentioned the right company being “within a few yards of the bushes which skirted the field on the right” and receiving fire from these bushes. This at first further suggests the wheatfield as their position. But, when describing the 4th Virginia, the National Tribune article put them “close upon the right flank…but were screened from us by the trees and bushes…they fired from the woods, not 20 yards from the right…” This virtually matches language in the manuscript, reconciling the two accounts and placing them in the scrub field. Finally, the manuscript describes their temporary withdrawal “into the woods…following an old road and reformed…in rear of and about seventy five yards from the edge of the wheat field in which Crawfords brigade had been engaged.” This makes a clear distinction between the two fields.[7]

Returning to Ruger’s report, “the enemy’s lines extended beyond the right of ours considerably, overlapping my regiment sufficiently to give by an oblique fire of that part of their line a most destructive cross fire on the right wing of my regt. The enemy also had a force on the right which opened a flank fire on the regt.” This part of Ruger’s report could support either interpretation. But, Hinkley’s manuscript and his National Tribune article have clarified that description, reconciling it with the scrub field. A portion of Ruger’s contemporaneous report further resolves this issue. Ruger included what he described as “a rough sketch of the relative position of the forces.” That drawing was omitted from the published Official Records, but is included here. Like Bryant’s history and Hinkley’s National Tribune article, Ruger’s drawing reflected the Stonewall Brigade reports, though without the benefit of having read them. The key aspect of the drawing is that it showed the 3rd Wisconsin north of the ridge that separated the wheatfield and the scrub field. Moreover, it depicted the 46th Pennsylvania, the right of Crawford’s brigade, south of this ridge, over which Ruger could have seen on horseback. It also depicted woods, rather than a field, on his right.[8]

The whole affair lasted no more than three minutes and resulted in a proper mauling, with 80 Federal casualties out of 267 engaged. These men reformed in a wooded ravine and returned to the line when their brigade advanced for another lopsided contest. This time their brigade briefly fought the Stonewall Brigade followed by two fresh Confederate brigades.[9]

Determining whether six companies fought in a field or in the next field over may be a little trivial. But, the action was anything but trivial for the 80 Federal casualties and the handful in the Stonewall brigade. One such member was Captain Moses O’Brien, commanding Company I in the center. A Confederate ball injured his thigh badly. When Companies I, D, and F rallied in a wooded ravine, O’Brien tied a tourniquet over his wound, as blood pooled in his shoe. The detachment went forward again with the balance of Gordon’s brigade, as it raced to the wheatfield. O’Brien fell at the edge of this field with a ball through his body. He remained alive on the field for two days, suffering through the heat. He died after his men carried him to the hospital.[10]

The location of the initial fighting is important also because it did not happen in a vacuum. Better understanding informs how we conceptualize the larger scale initial fighting in the wheatfield. While not necessarily a final answer on the subject, Ruger’s drawing, combined with the other sources, certainly points to the fighting occurring in the scrub field before the Stonewall Brigade wheeled right to the edge of the wheatfield to engage Crawford’s right directly. Finally, based on an assessment of the topography and these accounts, it appears increasingly possible to approach ground truth for this action, which can help to inform preservation goals for this battle.

————

Chris Bryan received his Bachelor of Science degree in History from the United States Naval Academy and Master of Arts in Liberal Arts from St. John’s College. He is currently working towards his Master’s degree in Historic Preservation from the University of Maryland. Chris is publishing a book with Savas Beatie titled, Resurgent Stars: Banks’ Corps from Slaughter’s Mountain to the Dunker Church.

[1] OR 12, Pt. 2, 151; Robert Krick, Stonewall Jackson at Cedar Mountain (Chapel Hill, 1990), 144-145; George H. Gordon, Brook Farm to Cedar Mountain: In the War of the Great Rebellion, 1861-1862 (Boston, 1883), 284-285; Charles W. Boyce, A Brief History of the Twenty-eighth Regiment New York State Volunteers (Buffalo, NY, 1896), 35; Marvin, The Fifth Regiment Connecticut Volunteers: A History Compiled from Diaries and Official Reports (Hartford, 1889), 155.

[2] Washington L. Hicks, Diary, 11, Chandler B. Gillam Papers, LoC; OR 12, Pt. 2, 151, 189, 192, 200.

[3] OR 51, Pt. 1, 123; Gordon, Brook Farm, 284

[4] OR 51, Pt. 1, 124; National Tribune, February 28, 1895; Gordon, Brook Farm, 202; Hinkley, Third Wisconsin, 33; Bryant, Third Wisconsin, 82; Julian Wisner Hinkley, “Handwritten Essay on the Civil War,” Julian Wisner Hinkley Papers, Wisconsin Historical Society, 19-20.

[5] Hinkley, 3rd Wisconsin, 33-34; OR 51, Pt. 1, 124 and 12, Pt. 2, 193-198; Krick, Stonewall Jackson at Cedar Mountain, 164-167.

[6] Bryant, 3rd Wisconsin, 82-83; OR 12, Pt. 2, 193-198.

[7] National Tribune, February 28, 1895; Julian Wisner Hinkley, “Handwritten Essay on the Civil War,” Julian Wisner Hinkley Papers, Wisconsin Historical Society, 20.

[8] Thomas Ruger, Cedar Mountain Battle Report, August 13, 1862, Union Battle Reports, 1861-1865 (Trifolded Segment) Unpublished, Vols. 11-13 (Box 4), Record Group 94, National Archives Records Administration.

[9] Hinkley, 3rd Wisconsin, 36; OR 51, Pt. 1, 124.

[10] Bryant, 3rd Wisconsin, 94-95.

Enjoyed this exploration quite a bit. By my calculations, the 3rd should have had a frontage of about 100 yards when deployed with 267 effectives. Figure in an additional +/- 20 yards off the right guide to account for the assertion of the rebel force firing from the bushes, and the battalion needs the scrub field to be at least 120 yards wide in order to not have Company H fighting from the slope of the “slight ridge.” Do we have any idea how wide it may have been? The map provided here suggests that it was no more than 200 yards, if that. Of course, this is all provided the battalion was in fact deployed and not merely in some sort of half-skirmish-cloud-mass-swarm-thing once they’re being actively rolled up and disintegrating. I only mention any of this out of the possibility that effective strengths for the rest of Crawford’s boys are available, which might allow for some assessment of what total frontage the brigade would have required at full interval — which might, in turn, allow for an argument re: whether or not there was ample frontage in said scrub field for the 3rd to ploy completely, or if they would have to have been in the wheatfield to do so. Just a thought!

Either way… can we talk about how ridiculous it is that the 4th Virginia chose to hammer away with a point-blank enfilade fire instead of simply rolling up the flank with the bayonet? So much for that brigade’s fascination with “cold steel,” I guess…

Thanks for this!

Thanks for the kind and thought-provoking comments, Eric!

The dimensions of both fields are elusive, particularly the Scrub, or brushy, field. Dr. Krick wrote that it was approximately 2/3 the size of the Wheatfield. Based on Colonel Ronald’s OR report, I calculated that it was approximately 500 yards long. (Incidentally, he did call for a charge bayonet!!) I have the eastern and western borders of the Wheatfield at 800 and 600 yards, respectively. With it approximately 600 yards at the road, tapering to about 200 yards on the northern border, gives an approximate area of 2,520,000 sqft. Multiplying by 2/3 and dividing by the 500 yd length from Ronald’s report yields 375 yards in width. That is wildly speculative. My map shows it a bit narrower than that and could certainly be off a bit.

The calculation above is driven by the Wheatfield dimensions. While also approximate and perhaps open to some adjustment, the Wheatfield is a little more susceptible to being nailed down. For the width at the road, I keyed the SE corner to a distance of 900 yards from the run, based on Geo. H. Gordon’s and Col. Andrews’ MHSM Papers essay. A few sources, including these, called the southern border at the road 600 yards, which could be a bit wide. But, two things support that. The rivulet and the low ground associated with it were generally described as 2/3 of the way across the field, heading west. This fits with the SE corner being 900 yards from the run. Dabney described the distance from the Gate to the SW corner as 1/3 mile. I’m showing it as 1/4 mile. But, Dabney also said that the woods north of the road terminated at a hillock, which is about at its end after 1/4 of a mile. 1/3 mile would put it right about at the rivulet.

The Wheatfield’s length has been described often at 800-1000 yards. I think I’ve even seen it at 1200 yards. I cut it off at what appears on the topo as a very distinctive ridge, which separates the two fields. This also lines up nicely with what I think is the ravine into which O’Brien and Hinkley fall back from the Scrub Field. This candidate ravine is also right along the likely path of Gordon’s Brigade as it advanced on the Wheatfield. The width of the northern border could be wider. I’ve seen it anywhere from 125 yards to 400 yards (relying on memory here a bit). An interesting detail, which is described in my forthcoming book, is that this layout of the Wheatfield creates a shape that, I believe, explains something that Gordon’s men describe seeing when attacked at the end of the day.

As to Crawford’s brigade…Crawford reported carrying 1679 infantry into the battle. Subtracting the 435 10th Mainers, who didn’t cross the Wheatfield during Crawford’s initial assault, leaves 1244 officers and men in the Wheatfield.

Thanks, again!

I visited Cedar Mountain a couple of weeks ago and walked the trail to the 3rd Wisconsin “monument”. I put that in quotations because it’s just a little stone stump to mark their placement. I know battlefields change over time, but from the terrain I saw, this collaborates well with the placement of the monument as well. I sorely could have used the upcoming ECW book on the battle for my trip. Thank you so much for this insightful post!

Thanks, Sheritta! Cedar Mountain is a great battlefield. I’m also looking forward to Mike Block’s forthcoming ECW book. He’s very knowledgeable, and I’m sure it will be quite useful.

Unfortunately, about 70 percent of the wartime “Wheatfield” stood on the east side of modern Route 642, land that is private property and thickly wooded today. In these woods, are monuments to the 28th New York, 27th Indiana, 46th New York, and 10th Maine, all of which are hidden from visitors to the park today. This is also the area where the 2nd Massachusetts was shot to pieces before the regiment could even form to meet the threats to its front and flank. Lastly, the construction of Rt. 642 has permanently altered the battlefield’s terrain by removing a large portion of the sloping hill that George Gordon’s regiments charged across as they met the Confederate brigades of Pender, Ronald, and Archer. It is my hope that one day this land will be preserved and protected.

I agree, Todd. That underlines the great work that’s been going on in Culpeper Co. in recent years to preserve the area and how important it is. To your point about Gordon’s Brigade, I’m quite struck by the effort of double-quicking up that hill, which you can see on the map above, through what was very dense undergrowth and during a punishing heat wave. That’s after heat exhaustion deaths on the march. Then they got to fight Ronald, Archer, and Pender! Thanks for the comment!