“Where Death Began”: Tragedy and Memory at the Allegheny Arsenal

ECW welcomes guest author Rich Condon

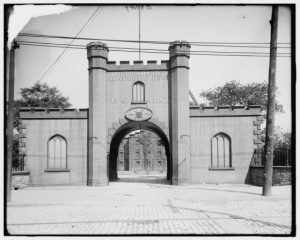

In the early afternoon hours of September 17, 1862, Joseph R. Frick, a local wagon driver, made his final rounds delivering three 100lb. barrels of gunpowder to the main laboratory of Allegheny Arsenal in Pittsburgh’s Lawrenceville neighborhood. As recalled years later by Arsenal Superintendent Alexander McBride, “A spark from the shoe of a horse in the team driven by Mr. Frick… precipitated what I long expected.”[1] The precipitation of McBride’s fear would come to be remembered as the largest industrial disaster of the American Civil War.

As if part of some violent climax coinciding with the fight at Antietam just under 200 miles away, tragedy struck at 2:00 pm. The grounds of Allegheny Arsenal were rocked by three separate explosions that day as loose gunpowder ignited along a macadamized road leading to the Arsenal’s laboratory, which consisted of several wooden structures. A total of 186 workers occupied the laboratory – 156 of whom were young women toiling to assemble ammunition for the ongoing Federal war effort. Of this number, 78 workers perished or received mortal wounds in the span of approximately six minutes.

Accounts from the following day illustrated the event in a light eerily similar to what one might expect from a horrific battle scene, and fittingly so, as local papers began to publish reports from the recent engagements at South Mountain and Antietam. The Pittsburgh Daily Post reported, “So great was the force of the explosion that fragments from the laboratories were thrown hundreds of feet. Shreds of clothing were found in tree tops… Of the main building nothing remained but a heap of smoking debris. The ground about was strewn with fragments of charred wood, torn clothing, balls, caps, grapeshot, exploded shells, shoes… Two hundred feet from the laboratory was picked up the body of one young girl, terribly mangled; another body was seen to fly in the air and separate into two parts; an arm was thrown over the wall; a foot was picked up near the gate; a piece of skull was found a hundred yards away, and pieces of intestines were scattered about the grounds. Some fled out of the ruins covered in flame, or blackened and lacerated with the effects of the explosion, and either fell and expired or lingered in agony until removed.”[2] “In the chest of one of the unfortunate victims,” as reported by the Pittsburgh Gazette, “eleven canister balls were found. She had evidently been killed by the explosion of a shell… In the side of another girl, seven Minie balls were discovered.”[3]

Fire companies from Lawrenceville and the city of Pittsburgh moved toward the scene to render assistance, as well as many bystanders in the surrounding streets, but much of the damage had been done by the time of their arrival. All they could do was extinguish the remaining flames and remove the dead and dying. The workers who did not perish in the initial explosions were subject to the ensuing fires and subsequent collapse of the structures surrounding them. Little over a week after the explosion, Reverend Richard Lea of the neighboring Lawrenceville Presbyterian Church described the resulting scene as one from a nightmare: “Some were dragged from a mass of ruins who had died in each other’s arms; some were rescued who would recover… Some could merely mention their names, or call for a priest, or for water, or for prayer, but all upon the ground were naked, blackened with powder… somewhat bloody, and with many the resemblance to the human form was completely lost… The victims lay about on boards and shutters, amidst a horror-stricken crowd, the trees above holding fragments of female attire, mournfully waving to and fro over their former owners.” The immediate and compulsive response from those who witnessed the tragedy varied from “the usual signs of sharp woe” to “solemn remarks” and “the stillness of stupefaction.”

An overwhelming majority of remains would never be positively identified, though in some cases such as that of Melinda Neckerman, the daughter of the Arsenal’s master mechanic, personal jewelry and clothing could be used to recognize what was left of the victims. Revered Lea recalled, “A parent would bend over some blackened corpse, examining minutely form, hair, any relic of dress, and then drop down silently if nothing was discovered, or shriek wildly if something certainly proved that these changed bodies were really the remains of their loved ones.”[4]

In a report to James W. Ripley of the U.S. Army Ordnance Department, Colonel John Symington, Chief of Ordnance at Allegheny Arsenal, noted that “the whole proceeds of the day … exploded, amounting to about 125,000 of .71 and .54 small arm cartridges, and 175 rounds of field ammunition assorted for 12-pounder and 10-pounder Parrott guns.”[5] At the height of the war it wasn’t uncommon for the Arsenal to turn out at least 30,000 rounds of small arms ammunition on a daily basis.[6] The ordnance assembled by the workers of Allegheny Arsenal that day was meant to deliver death to the enemy on a faraway battlefield; in a sadly tragic twist of fate, it brought devastation to the home front.

On September 18, the undistinguishable remains of 39 victims from the laboratory site were buried in government-furnished coffins just a mile away in a large lot donated by Allegheny Cemetery. This mass grave, although situated beyond the battlefield, resembled a scene that soldiers on the war front would find all too familiar. Those who could be identified were likewise buried at Allegheny Cemetery, as well as in neighboring St. Mary’s Cemetery.

Many of the young women who had been killed or wounded in the explosion had close familial ties to fellow workers, and likewise, many of those lost left several vacant chairs at the dinner table. Superintendent Alexander McBride, who had been working in one of the back rooms of the laboratory at the time of the explosion, sat adjacent to a room of nine workers including his 15-year-old daughter Kate. She fell victim to the fire and chaos within feet of her helpless father, who had been frantically attempting to extinguish the spreading flames before the building’s roof caved in – a scene that haunted the Superintendent for the rest of his life.

A coroner’s jury convened shortly after the incident in an attempt to uncover the cause of the explosion, and perhaps even expose those who may be held responsible for the conditions that allowed for such a tragedy to occur. Among those who came under public scrutiny were Alexander McBride and Assistant Superintendent James Thorp, as well as Colonel John Symington and his lieutenants, John R. Edie and Jasper Myers. The latter three parties of Symington, Edie, and Myers were considered guilty of gross neglect by several jurors. However, they were ultimately exonerated by an army investigation, leaving much of the blame for McBride and Thorp. An exact cause of the explosion was never officially decided upon by the jury, but according to several employees of the Arsenal, the common denominator and recipe for disaster lay solely in the accumulation of black powder on the road leading to the laboratory, as well as neglectful practices in dispersing the explosive material.[7]

In the aftermath of the explosion and ensuing trial, the surrounding community was left to recover on their own. Although gaps were left in the familial ranks, so to speak, the Arsenal continued to mass produce war material through the remainder of the conflict. Government assistance to community members, victims, and victims’ families had been sought after for years following the destruction of the Arsenal’s laboratory – to the point of an assembly held on September 22, 1890. This reunion of approximately 150 survivors and family members was called to order by Joseph R. Frick, who himself had been wounded in the initial blast at the Arsenal nearly thirty years earlier. Among the first to address the crowd was former Superintendent McBride, who submitted a petition to be sent to the United States Congress for compensation for “relief of the surviving sufferers… and the few and surviving relatives of the dead… Being sworn into service, they did their duty as did the soldier on the field of battle, and hereby urge their claim…” McBride, being among the survivors and relatives of the dead, shared his story with the audience, “I suffered with you all. I lost a beloved daughter. But I had more to bear than any of you who lost dear ones, or suffered personal injury. I was made to bear the brunt for a guilty one… To this day I often hear myself censured in the cars and on the street when passing the arsenal, and denounced as worse than any devil in hell. I was told to leave the city, and threatened with tar and feathers… I was innocent, and lived it out right here. Yet no one knows what I have suffered in those years.”[8]

In yet another sad turn of events, the assistance requested by the Allegheny Arsenal Explosion committee never came. As the United States entered into a war with Spain eight years later, the money that might have brought relief to those in need had gone toward the efforts of foreign conflict. The Arsenal grounds eventually gave way to the desire for a community park, and little remains of the site of so much loss. Marking the mass grave of the unknown victims is a stone monument to their sacrifice, with immortal words etched in bronze: “Tread softly this is consecrated dust, forty-five pure patriotic victims lie here. A sacrifice to freedom and civil liberty, a horrid moment of a most wicked rebellion. Patriots! These are patriots graves, friends of humble, honest toil, these were your peers. Fervent affection kindled these hearts, honest industry employed these hands, widows and orphans tears have watered this ground. Female beauty and manhood’s vigor commingle here. Identified by man known by Him who is the resurrection and the life, to be made known and loved again, when the morning cometh.”

[1] “Action After Many Years” Pittsburgh Daily Post. September 22, 1890.

[2] “A Direful Calamity” Pittsburgh Daily Post. September 18, 1862.

[3] “Appalling Disaster! Explosion at the U.S. Arsenal” The Pittsburgh Gazette. September 18, 1862.

[4] Rev. Richard Lea, “Sermon Commemorative of the Great Explosion at the Allegheny Arsenal at Lawrenceville, Penna on September 17th, 1862,” Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, September 28, 1862.

[5] Arthur B. Fox, Pittsburgh During the American Civil War: 1861-1865, (Mechling Bookbindery 2002), 118.

[6] “Where Death Began” The Pittsburgh Dispatch. November 2, 1890.

[7] “The Late Explosion at the Arsenal – Verdict of the Coroner’s Jury” The Pittsburgh Gazette. September 29, 1862.

[8] “Action After Many Years” Pittsburgh Daily Post. September 22, 1890.

Thanks for this reminder that the Civil War was not exclusively about battles and skirmishes. An incident such as the one described above took place at Tredegar Iron Works (March 1863); and in camps/ fortifications across wartime America when soldiers were required to remove old, time-expired (and unstable) explosives from artillery shells. Sometimes men were smoking while performing this duty; other times an object would be mishandled (as occurred at Tredegar.) In April 1863 USS Preble was lost on Pensacola Bay when “minor maintenance” being conducted by the Navy Yard sparked a fire that engulfed a magazine that had not been emptied.

One can never be TOO Safe when handling explosives.

Absolutely tragic. I first read about the explosion at Alleghany Arsenal from the book “Gunpowder Girls”, which endeavors to give a detailed analysis of other arsenal disasters during the war. it’s a great follow-up for anyone looking to learn more about the girls or the other explosions like in Richmond and Washington. Thank you for the post!