Lessons for 2020 from POWs and Sieges

Being captured in battle can be a dramatic and traumatic experience. Instantly you are cut off from what was familiar and definite, and cast into a situation unfamiliar, out of your control, and with a most indefinite future.

The same is true of being surrounded and placed under siege, facing pressures from the enemy ringing your position while hopefully awaiting relief. Earl Ziemke in Stalingrad to Berlin summed up the effects well: “A sudden encirclement of a modern army is a cataclysmic event, comparable in its way to an earthquake or other natural disaster. On the map it often takes on a surgically precise appearance. On the battlefield it is a rending, tearing operation that leaves the victim to struggle in a state of shock . . . Escape is the first thought in the minds of commanders and men alike, but escape is no simple matter.”

These have been on my mind over the past few months, as in broad parallel this is what has happened when coronavirus hit the United States and prompted lockdowns starting in mid-March 2020. I have been reaching into accounts of both prisoners of war (POWs) and besieged forces to try and get perspectives about what is going on, and the stresses they faced. I also wanted to see how they coped in those situations in case any of those lessons might be applicable now.

This post summarizes my findings so far.

As I read through various accounts, it struck me to see a similar sort of emotional roller coaster as many have experienced in 2020. First the pandemic was believed to be of short duration, then a bit longer, then longer, and now there is a general rise in stress and dread (at least here in Wisconsin) at the resurging case counts and the prospect of this lasting into and through the winter. Prisoners captured on Java in March 1942, and discussed in Jim Hornfischer’s book Ship of Ghosts, went through similar emotional waves on a closely-aligned timeline. Christmas 1942 for many Pacific POWs was quite depressing, and seemed to get more so in 1943 and 1944. POWs in other places and wars, like General Wladyslaw Anders in the USSR and Commander James Stockdale in Vietnam, noticed a similar up-and-down effect and worked to combat it.

Sieges, particularly longer ones, also revealed rising emotions because of the stress of the situation. Life during the Siege of Corregidor in 1942 was a day-to-day existence, and divisions opened between those stationed underground in Malinta Tunnel and those stationed outside in the island’s defenses. In Leningrad’s 900 days of siege 1941-44, all forms of human emotion and conduct manifested themselves. These are two examples, but many more can be found, especially in longer sieges lasting months or more than a year.

Some people kept diaries, both as a way to document events and also sometimes to give vent to the stress of their situation. Their accounts offer insights into their thoughts and feelings at particular moments. (Two of the better examples of these are General Charles “Chinese” Gordon’s diary from the 1884-85 Siege of Khartoum and General W.E. Brougher’s World War II POW diary published as South to Bataan, North to Mukden.)

At the end of the day, it seems that people who sustained themselves through these events found personal support, either through religion, mission, willpower, or some other internal source. Community also mattered, ranging in size from as small as a mess (or family) to as large as a company or in some cases even a battalion of people committed to supporting and sustaining each other as best possible. Indeed, unit cohesion was one of the best predictors of survival and success both under siege and in POW camps.

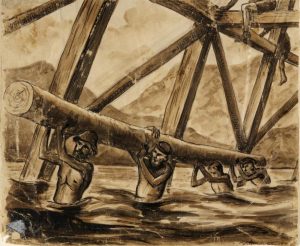

Three quotes I found in Hornfischer’s book seem worth repeating here. All three men were on the Railway of Death in World War II:

“I lived day by day. I didn’t worry about yesterday or tomorrow. Really, to me that was the best way to keep your sanity and your wits about you – just what’s going to happen today and nothing else.” – Sergeant Roy Offerle, USA

“There are three forces at work here, like legs of a triangle. First food. Either we have enough or we’re dead. Second, health. That needs no explanation. Third, attitude, which is probably the best medicine. Food, health, attitude. They’re interlocked, each totally dependent on the other. We have to have all three. No food, no health. Bad attitude: the triangle collapses.” – Private Jim Gee, USMC

“Suffer is a dangerous word here just now – it can induce self-pity. Endure is a better word, it is not so negative. Enduring can give an aim, a sense of mastery over circumstance.” – Chief Quartermaster Ray Parkin, RAN

These words may be helpful in these times. I encourage our readers to find examples for yourself, both to learn but also to find perspective and inspiration in these difficult times.

Some interesting things here to digest and consider. Good stuff as always from you Chris!

Thanks!

Books recommended are great reads .

I have read a number of the works cited and concur with your thoughts on this.

Thanks!

Thanks for this topic. Folks interested in the Andersonville experience may want to check out my research and books. https://www.amazon.com/Hirams-Honor-Reliving-Private-Termans/dp/0615278124/ref=nodl_

Once a month I read the Salisbury Confederate Prison Association

newsletter. Descendants publish wave after wave of brief bios of the Union soldiers who interned at Salisbury and very often died there. My great grandfather was a prisoner at Salisbury from August 1864 till February 1865 when he escaped or was let go … the record is unclear. Pat Donohue never recovered from his war experiences especially the months starving and living in caves. But he survived because of the men he dwelled and escaped with, I believe. Thanks so much for the article. It gave me a deeper insight into his Salisbury experience.