A Doctor, His Enslaved Man, and Georgia’s Union Circle (part two)

The devastation and upheaval created in the neighborhood near the Battle at Resaca gave people like Dr. Gideon’s enslaved man, Owen, their first viable opportunity to aid the Union cause. Owen Gideon was born into slavery about 1834 in Hall County, Georgia. Owen was five feet, eight inches tall, a cobbler by trade, and a farm hand by necessity on the small cultivated acreage owned by the doctor.

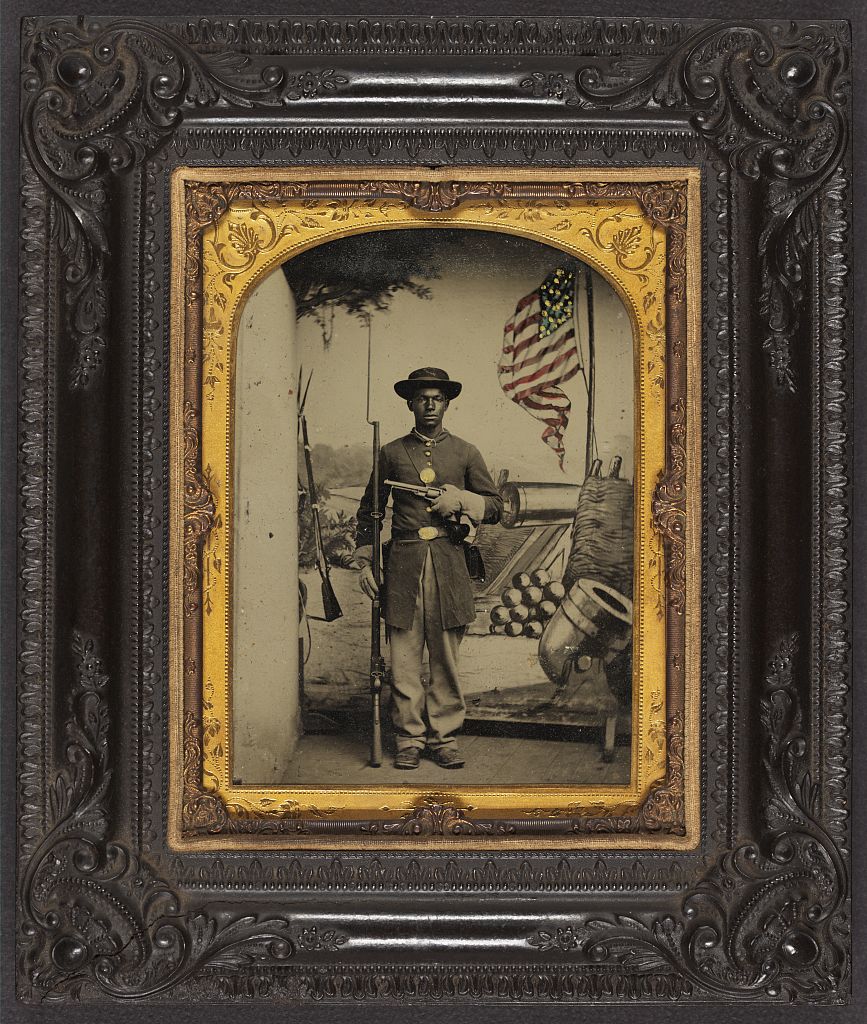

Once the U.S. Army secured the region, recruiters scoured the countryside, encouraging recently enslaved men to abandon their former masters and help fill the ranks of the newly-established Forty-Fourth U.S. Colored Infantry Regiment, which had begun enlisting Rome-area blacks in early May. Their colonel, Lewis Johnson, and the commissioned officers were white men. In June, 1864, pay of black Union troops was increased to $13 per month to gain parity with the pay for white volunteers. A call to fight for their own freedom was irresistible to many men who scarcely dreamed that their jubilee might actually arrive, so the regiment’s ranks filled rapidly.

Owen left the Gideon farm in early June. Alongside thousands of other black refugees, he headed north, filling small towns like Chattanooga and Hamilton, Tennessee, with newly-liberated former slaves. He may have had the assent of his master, who gave him, in Owen’s own words, “my first lesson in radicalism.”[1]

Owen Gideon enlisted in Co. E of the Forty-Fourth U.S. Colored Infantry on June 5, 1864. He and 41 others somehow avoided capture when the regiment was confronted at Dalton in October by John Bell Hood’s Army of Tennessee and forced to surrender. Dozens of his comrades were either imprisoned in Griffin or Columbus, Georgia, sent to work on rebel fortifications in Mississippi, or returned to their former masters. Their white officers were paroled and released.

Owen Gideon and a reorganized Forty-Fourth Colored Infantry left Chattanooga at the end of November, bound for Nashville. They were part of a force sent to help defend the city against a desperate attempt by John Bell Hood to disrupt Sherman’s supply lines and defeat the army led by George H. Thomas. Unfortunately, the train carrying them derailed seven miles north of Murfreesboro, Tennessee, on December 1. Union troops rushed toward the shelter of Blockhouse Number 2 near Mill Creek Bridge, but General Nathan Bedford Forrest’s rebel cavalry were already in the area. Twelve black soldiers were killed and 46 were wounded. The following day, 33 men, including Owen Gideon, were captured and placed in a holding pen. After two days without food, the prisoners were marched through the snow to Meridian, Mississippi. Gideon stole a blanket from a rebel captain on the way and slept better than many of his fellow captives.[2]

Owen Gideon did forced labor in Meridian for more than five months, finally escaping his confinement in May 1865. By the time he had walked nearly three hundred miles back to Calhoun, he was exhausted and sick. Dr. Gideon nursed him back to health, and he returned to his regiment at Dalton on June 16. Owen served the balance of his term of enlistment, was honorably discharged, and mustered out on April 30, 1866.

Dr. Gideon offered Owen the opportunity to move back and run the farm, as his younger son Gilead had moved to Arkansas. The formerly enslaved man said he “would have done so if I could have lived there in any safety.”[3] Instead, Owen Gideon settled in the Turkey Foot neighborhood of Hamilton, Tennessee, across the river from Chattanooga, where he married Nettie Clark and worked as a shoemaker. The couple had fourteen children before Owen died in his early 70s in 1905. His widow collected his pension until 1924 and died sometime after 1930.

Dr. Gideon never recovered financially from the war. Few neighbors had money to pay for a physician of his talents. He and his neighbors struggled for years just to feed their families. He became a leader in the Gordon County Republican Party in the post war years, but he and his allies had little power or influence. In 1870, for example, the party decided not to field a local candidate for the state legislature.[4]

In 1872, Dr. Gideon applied for war damages to the Southern Claims Commission. Owen Gideon served as one of his witnesses. After a thorough investigation by claims commissioners, Dr. Gideon was found to have been a loyal man throughout the rebellion; yet most of his claim of more than $10,000 in damages was rejected, and he received only $975 from the U.S. government. The commissioners paid only for legal takings of food and supplies needed by the army. Pillaging done by renegade Union troops was not reimbursed, and although he was judged innocent in the train bombing, the cost of his burned home also did not qualify.[5] He died on his farm north of Calhoun in 1884 at the age of 82.

While the brave deeds of local Confederate soldiers were celebrated in Civil War memory, Gordon County’s significant Union circle has been largely forgotten. Scores of Georgians remained loyal to the U.S. government despite danger to themselves and their families. Dissent on the home front did considerable damage to Confederate efforts to form a separate republic to preserve slavery. White Unionists and their enslaved counterparts encouraged and protected deserters, actively aided Federal troops, and, in the case of men like Owen Gideon, liberated themselves from perpetual bondage by fighting for their country in America’s bloodiest conflict. Remembering them adds a balanced perspective to Civil War history.

David T. Dixon is the author of Radical Warrior: August Willich’s Journey from German Revolutionary to Union General. His website is http://www.davidtdixon.com.

[1] Claim #11,472, Berry W. Gideon, SCC. Testimony of Owen Gideon.

[2] Owen Gideon Pension File WC599132, Civil War Pension Files and Compiled Service Records, RG 94, National Archives, Washington, DC. William A. Dobak, Freedom by the Sword: The US Colored Troops, 1862 ? 1867 Washington, D.C.: Center for Military History, 2011), 287 ? 89.

[3] Claim #11,472, Berry W. Gideon, SCC. Testimony of Owen Gideon.

[4] Sugar Planter (Port Allen, LA), 4 May 1867 reported that 75 women walked as much as ten miles into Calhoun in one day seeking food. The Weekly New Era (Atlanta), 5 October, 1870.

[5] Claim #11,472, Berry W. Gideon, SCC.

Very interesting