Re-evaluating Ezra Carman: Triangulating the 2nd South Carolina’s Second Assault at Antietam

Emerging Civil War welcomes back guest author Chris Bryan…

Ezra Ayers Carman, who commanded the 13th New Jersey at Antietam, wrote a seminal work on the Maryland Campaign based upon correspondences with veterans during the 1890s and 1900s. It is a magisterial work and highly recommended. Nevertheless, some details deserve reexamination.

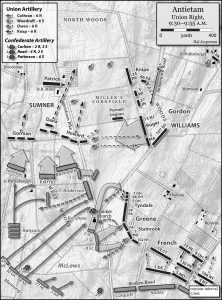

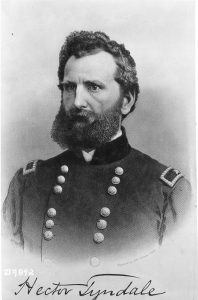

The 2nd South Carolina Infantry made two assaults near the Dunker Church at the Battle of Antietam. This essay explores the 2nd South Carolina’s second assault, occurring at approximately 9:30 a.m., from three perspectives: the 2nd South Carolina, which attacked from the West Woods; Lieutenant George Augustus Woodruff’s Battery I, 1st U.S. Artillery, which was posted just south of the D. R. Miller Cornfield; and Lieutenant Colonel Hector Tyndale’s Federal brigade, defending the north end of a low plateau across the Hagerstown Pike from the Dunker Church. The result of this reassessment is an updated interpretation of each of these units’ fighting.

After roughly three hours of battle, the Confederate left faced imminent collapse. Three divisions under Maj. Gen. Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson had fought themselves out against the Union I Corps, with only one fresh Confederate brigade in reserve. Three brigades of Maj. Gen. D. H. Hill’s division shifted left from the Confederate center. The small Union XII Corps fought and soundly defeated these brigades. In doing so, it permanently cleared the East Woods and the Miller Cornfield. Two brigades of Brig. Gen. George Sears Greene’s division then created a lodgment, temporarily without ammunition, on the ridge east of the West Woods and the Dunker Church. Meanwhile, a green regiment from Brig. Gen. Samuel Wylie Crawford’s brigade, the 125th Pennsylvania, advanced without support into the West Woods and just beyond the Dunker Church. Other Federal units from the morning’s fighting were scattered around the edges of the West Woods. Most soon cleared the way for a fresh veteran Federal division that drove west across the Hagerstown Turnpike and into the West Woods, which until moments before held little more than a single Confederate brigade.[1]

As Maj. Gen. John Sedgwick’s Federal division, of Maj. Gen. Edwin Vose Sumner’s II Corps, drove headlong into an empty portion of the West Woods with an exposed southern flank, Confederate Maj. Gen. Lafayette McLaws’ division deployed in the fields southwest of the West Woods following an overnight march from Harpers Ferry. Portions of this division drove off the 125th Pennsylvania, then pitched into Sedgwick’s flank, alongside the Confederates already in the woods. Confederate Brig. Gen. Joseph Brevard Kershaw’s South Carolina brigade, of McLaws’ division, went after other Federals.[2]

As his brigade arrived southwest of the West Woods, Kershaw sent the 2nd South Carolina ahead to cover the brigade’s deployment. It advanced east in column then faced north into line and entered the woods heading towards the Dunker Church and the 125th Pennsylvania. The 2nd bore down on the Pennsylvanians’ left flank as the right half of Brig. Gen. William Barksdale’s brigade hit the Pennsylvanians’ right. The Federals, one month from home, buckled after a respectable resistance and fled along the north side of the Smoketown road, which begins across the Pike from the Dunker Church and runs northeast to the East Woods.[3]

The 2nd South Carolina then brushed off other Federal regiments, which had arrived behind the 125th, before crossing the Pike south of the Smoketown road and halting about where the Maryland Monument is today. The 2nd formed a disjointed V-shape, with its left on the rock ledges close to the Smoketown road, firing on retreating Federals north of the road. The right surged toward what appeared to be open high ground to the east. They soon discovered Tyndale’s XII Corps Federals, freshly resupplied with ammunition, and quickly returned to the woods under Tyndale’s fire. Much of the 2nd rallied in the woods south of the Dunker Church and discovered the 7th and 8th South Carolina approaching, marching east along the southern edge of the woods toward the Dunker Church Plateau. After a brief reunion, the three regiments advanced.[4]

Up to this point, Ezra Carman thoroughly described these events. However, an unfinished portion of Carman’s manuscript creates a gap in the narrative. It ends after the 2nd South Carolina’s initial assault, omitting subsequent attacks by Kershaw’s full brigade followed by Col. Van Manning’s brigade. It resumes after Greene’s men entered the West Woods. Carman’s first-rate Antietam Atlas does depict these events. It shows the 2nd, 7th and 8th South Carolina, from left to right, all advancing east on the south side of the Smoketown road against Greene’s Federals on the Dunker Church Plateau, with Lt. Col. Tyndale’s brigade to the north and Col. Henry Stainrook’s brigade to the south. Secondary literature to date reflects this interpretation, with the 2nd attacking the oversized 28th Pennsylvania on the left of Tyndale’s line. Tyndale’s right contained three undersized Ohio regiments. This essay agrees that the 7th and 8th South Carolina assaulted the 28th Pennsylvania and Stainrook’s brigade, making a run at Battery A, 1st Rhode Island Artillery, which was posted between Greene’s two brigades. However, primary sources suggest that the 2nd South Carolina did not return to the same ground over which it initially advanced. This essay suggests that the 2nd South Carolina advanced north of the Smoketown road and attacked Tyndale’s Ohioans.[5]

Carman’s conclusion about the 2nd South Carolina’s second assault appears to have been based on C.A.C. Waller’s June 7, 1901 letter. Waller, a member of the 2nd South Carolina wrote, “the 3 regiments 2nd, 7th, and 8th made a magnificent charge. The left of the 2nd touched + enveloped the church.” This can be plausibly interpreted as the three regiments in a continuous line. However, Waller did not explicitly state that, and that interpretation contradicts Waller’s December 14, 1899 letter, which explicitly described an advance that “went by church over Pike across or to north or northwest of the road forking with the Pike + up another swale hollow or depression over clover field to + up to a fenced thrown or knocked…” The field north of the Smoketown road contains a significant swale. Waller’s description is further supported by the initial direction of the 2nd South Carolina’s second advance. If the 2nd left the other two regiments in the southeast corner of the woods, it would have had to go north to envelop the church. Passing the church to its left, heading mostly north, would take it north of the Smoketown road and into the swale as described in the December 14 letter. There are no known extant sources, other than the line from the June 7th Waller letter, that suggest 2nd South Carolina’s second assault was next to the 7th. The movement that Waller described would cause them to attack Tyndale’s Ohio regiments.[6]

Now we turn to the perspective of 1st Lt. Woodruff and his battery. This is another point where Carman appears mistaken. Woodruff had advanced in the wake of Sedgwick’s division and went into battery south of the Cornfield and east of the Hagerstown Pike. Another battery, commanded by Capt. George Cothran, joined on Woodruff’s right. Woodruff’s and Cothran’s targets were mainly Barksdale’s brigade and the 3rd South Carolina of Kershaw’s brigade, which had followed behind Barksdale through the West Woods before spilling onto this field next to the Pike. Enfiladed by Woodruff’s guns, the 3rd South Carolina turned toward the Pike, took cover in a small swale and waited.[7]

Carman depicted Woodruff’s guns on the atlas in the bottom of the swale north of the Smoketown road, pointing down the swale toward the Dunker Church. This appears based on a battery member’s account from the unit history, which uses distances 350 yards north and 150 yards east of the Dunker Church. In the position that Carman depicted, Woodruff would have had a significant ridge near his right flank. The Pike was at the top of this ridge. Standing in this spot, Woodruff could not have seen any Confederates west of the Pike, his guns could not have hit those targets, and his battery would have faced a dire threat if Confederate infantry arrived atop the ridge. From that position, the only targets that would ever present themselves were in the immediate vicinity of the church. The 3rd South Carolina and Barksdale’s brigade were never at the church. It is unclear why Carman used the source that he did, but Woodruff’s report placed his battery 300 yards from the West Woods. Measuring from either the south or the west end of the open field between the West Woods and the Pike puts his battery just on top of the high ridge east of the Pike and on level ground with everything between that spot and the West Woods.[8]

Woodruff’s position is important, because if Carman’s depiction was correct, a move by the re-formed 2nd South Carolina into that swale, and straight at the front of Woodruff’s guns, would have been very short-lived. Woodruff reported firing solid shot on a body of Confederates that exited the woods at the church. He described these troops moving “over to our left in such a way as to be almost entirely covered from our fire by the peculiar nature of the ground. A change of front was impracticable from the want of time, and the fact that while protecting one flank we should expose the other.” With Woodruff on top of the ridge, the swale would have covered the South Carolinians from his guns until they were on his flank. This accounts for the “peculiar nature of the ground.” If Woodruff had been down in that swale, pointed at the church, the Confederate body on his left would have been at the Mumma House lane and behind Tyndale’s brigade, which is not likely.[9]

Woodruff repositioned to the front of the East Woods, north of the Smoketown road. This allowed the 3rd South Carolina to advance from its swale. Colonel James Nance led the 3rd from its covered position and “up the hill across a small road, climbed a fence, and passed to the summit of a hill in a freshly plowed field.” This advance was only as far as the same high ground that Woodruff departed and a bit further south. Colonel Nance reported moving to support the assault of the rest of his brigade that was headed against Tyndale. The 2nd South Carolina, moving through the swale and then turning right onto the Ohioans on Tyndale’s flank, makes sense as the force that dislodged Woodruff. And the timing is correct.[10]

Finally, from the XII Corps’ perspective: Lt. Col. Hector Tyndale’s memoir, which does confuse details at times, indicated that there were three assaults. The first assault appears to have been the isolated attack by the right of the 2nd South Carolina. The second was by the 7th and 8th against the left of the 28th Pennsylvania, the Rhode Island Battery and the 111th Pennsylvania. According to Tyndale, the third attack was on his right flank.[11]

A 7th Ohio private, Joseph Clark, described Confederates advancing “across the field directly in our front, passing obliquely to a point where they were sheltered by the woods, and for a time hidden entirely from our view.” The Alexander Gardner photograph, View where Sumner’s Corps charged, gives some hint at this. The view is to the north from a point on the Dunker Church Plateau south of where the Ohioans stood. The Dunker Church is barely off camera to the left. The swale beyond the Smoketown road is discernible, as is the ridge beyond the swale, where Woodruff had been posted. Remnants of trees are visible about where trees are today by the Maryland Monument. It is unclear whether the trees in the photograph were north or south of the Smoketown road. When standing on the field where the Ohioans stood, it is clear how the Ohioans might have lost track of infantry moving through that swale and behind the trees.[12]

Clark then wrote that these Confederates “completely surrounded” them on the right. Moreover, Tyndale described this assault on his flank as coming “en masse down a hill and through a cornfield. A knoll across the Smoketown road from the Ohioans’ flank appears to be the hill up which the South Carolinians advanced from the swale and down which they attacked. Tyndale may also have described the 3rd South Carolina, which remained on high ground on the north side of the swale. Waller described the 2nd South Carolina moving through a swale and up to a fence [bordering the Smoketown road]. The knoll just across the Smoketown road from the Ohioans would fit Clark’s description. Clark wrote that they thought all was lost but they changed front to meet the attack. Tyndale’s cornfield is a mystery. Several unsubstantiated cornfields were mentioned throughout this area.[13]

The South Carolinians’ effort against the Ohioans was short-lived. Tyndale wrote that the flank attack “was met by a terrific oblique fire, which melted down their ranks like wax.” Moreover, Waller described in the December 14 letter that after they reached the fence, Federal artillery “began furiously to burst forth hurtling rails, dust + shells + we began to fall back sullenly at first then rapidly until we reached the church.” This artillery was likely Woodruff and Cothran, returned to the edge of the East Woods and now on the South Carolinians’ left flank.[14]

In summary, the only sources supporting the traditional narrative of the second assault occurring south of the Smoketown road are the Carman-Cope Atlas and the June 1901 Waller letter, which merely stated that the 2nd, 7th, and 8th all attacked together, but was not explicit about where. The three perspectives cited above fit together neatly. They strongly point to a necessary reinterpretation of the 2nd South Carolina’s second effort at Antietam.

[1] Ezra Carman, Maryland Campaign of September 1862, Vol. 2: Antietam, ed. Thomas G. Clemens (El Dorado Hills, CA, 2012) 128-140, 157-158, 178-179

[2] Carman, Maryland Campaign, Vol. 2,186-194.

[3] OR, Vol. 19, Pt. 1, 491-493, 865-866, 868-869, 883.

[4] C.A.C. Waller to Ezra Carman, December 14, 1899, National Archives Records Administration-Antietam Studies (hereafter, NA-AS); Carman, Maryland Campaign, Vol. 2, 234; OR, Vol. 19, Pt. 1, 308; John M. McLaughlin, A Memoir of Hector Tyndale, Brigadier-General and Brevet Major-General, U. S. Volunteers (Philadelphia, 1882) 102-103; Grand Army Scout and Soldiers Mail, September 22, 1883.

[5] United States War Department. Atlas of the battlefield of Antietam, prepared under the direction of the Antietam Battlefield Board, George W. Davis, Ezra A. Carman, U.S.V, Henry Heth. Surveyed by E. B. Cope, H. W. Mattern. Drawn by Charles H. Ourand. Position of troops by Ezra A. Carman. Published by authority of the Secretary of War, under the direction of the Chief of Engineers, U.S. Army (Washington, D.C, 1908) Map. https://www.loc.gov/item/2008621532/.

[6] C.A.C. Waller to Ezra Carman, June 7, 1901 and December 14, 1899, NA-AS.

[7] OR, Vol.19, Pt.1, 868-869; Carman, Maryland Campaign, Vol. 2, 213-214.

[8] Carman, Maryland Campaign, Vol. 2, 214; OR, Vol. 19, Pt. 1, 310.

[9] OR, Vol. 19, Pt. 1, 310.

[10] Ibid., 310, 869; Carman, Maryland Campaign, Vol. 2, 226.

[11] John M. McLaughlin, A Memoir of Hector Tyndale, Brigadier-General and Brevet Major-General, U. S. Volunteers (Philadelphia, 1882), 55-56.

Tyndale also wrote that this third attack on his line immediately preceded the Federal advance, not covered by this narrative, that entered the West Woods. After the 2nd South Carolina’s second assault and before Tyndale’s advance, another Confederate assault by the 30th VA, 48th NC, and, sort of, by the 46th NC, landed against Tyndale’s front and right. But, it did not penetrate far, and it appears that it was close on the heels of the 2nd South Carolina’s assault. Therefore, it appears that the two were, perhaps correctly, conflated by Tyndale as a single assault.

[12] Joseph Clark to John Mead Gould, March 18, 1892, Antietam Papers, Dartmouth College. Alexander Gardner, photographer. Antietam, Maryland, View where Sumner’s Corps charged. United States, 1862. Sept. Photograph. Civil war photographs, 1861-1865, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division; https://www.loc.gov/item/2018671467/; McLaughlin, Memoir of Hector Tyndale, 55-56.

Clark’s letter is difficult as well. What throws Clark’s account into some doubt is his chronology. He described a new New Jersey regiment [13th] arriving and breaking, then he described the flank attack recounted in this narrative. The 13th New Jersey actually broke later in the day, from within the West Woods. Moreover, the Ohio regiments were ordered from the woods prior to that, relieved by the 13th New Jersey. What perhaps saves Clark’s account is that immediately after describing the flank attack, he described the Ohioans taking prisoners, getting more ammunition and then going into the woods. All of that is correct immediately after the flank attack at the Dunker Church Plateau. As such, it appears that the anecdote about the 13th New Jersey was an outlier and that the rest is a reliable chronology.

[13] Joseph Clark to John Mead Gould, March 18, 1892, Antietam Papers, Dartmouth College; McLaughlin, Memoir of Hector Tyndale, 55-56; C.A.C. Waller to Carman, December 14, 1899. The attack toward Tyndale’s right by the 30th Virginia, which occurred after the 2nd South Carolina’s second attack, came nowhere close to where an envelopment or a downhill assault would make sense.

[14] McLaughlin, Memoir of Hector Tyndale, 55-56; C.A.C. Waller to Carman, December 14, 1899; OR 19, Pt. 1, 310.

Interesting article. The back and forth around the West Woods and the Dunker Church have fascinated me when I visit Antietam and try to understand the terrain. The Gardner photo really helps to interpret that area.

Thanks, Bill! I’m glad you liked it. I completely agree about understanding that area. There are so many layers of history that occurred on that northwest portion of the field in just 8-9 hours. Plus, the terrain is deceptive. It seems like it’s fairly straightforward standing in one spot, say at the plateau where that Gardner photo was taken. But, while the topography isn’t dramatic, the perspective sure changes as you walk the ground from different directions.

Ezra Carman incorrectly analyzed Conf. Gen. John Bell Hood’s two brigades at South Mountain and later authors never discovered Carman’s oversight. Now, my latest book, Hood’s Defeat Near Fox’s Gap September 14, 1862, tells the true story of Hood and his men at South Mountain. Carman incorrectly placed Hood’s two brigades over one half mile from their actual location in the battle. This incorrect analysis by Carman threw a negative view on the Union performance in the battle. Fortunately, I discovered Carman’s error and have made the true story of Hood at South Mountain available for Civil War readers.