How a Camp Became a Fort

Emerging Civil War welcomes back guest author Sheritta Bitikofer…

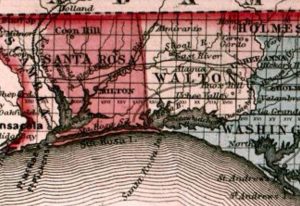

In the panhandle of Florida, a place that is not known for much else besides white sand beaches and prime fishing, sits a little-known and bypassed fragment of Civil War history that shaped a well-beloved city.

The state became a part of the Confederacy on January 11, 1861, and mustered 15,000 men to fight in the war. A group of ninety-two men from Walton and Santa Rosa Counties gathered in Eucheeanna to form a new company. Captain William McPherson led the farmers who fashioned themselves as The Walton Guards. Lieutenant Henry W. Reddick wrote, “the ladies of the county hoisted that flag [of the Walton Guards] and marched around old Eucheeanna and made a direct appeal to each man : ‘Go, boys, to your country’s call! I’d rather be a brave man’s widow than a coward’s wife.’” They sailed aboard the schooner Lady of the Lake to Garnier’s Bayou to serve as the eyes and ears for Confederate General Braxton Bragg who was stationed at Fort Barrancas. [1]

In 1861 it was evident the East Pass at Santa Rosa Island needed to be monitored. Two Union gunboats blockaded the area, making the Confederates in Pensacola nervous. If the Federal navy could slip through to Union-held Fort Pickens, they could resupply and reinforce the fortification. The Walton Guards began defending “The Narrows”, a shallow inlet between the mainland and Santa Rosa Island. The Walton Guards set up their camp around an Indian midden mound on the mainland side of “The Narrows”, once home to Mississippian natives, and dubbed it Camp Walton. Reddick remembered, “We soon had the camp ground and drill grounds cleared up and set to work building our houses, and in about a week we were all fixed and had a jolly good time.”

In 1861 it was evident the East Pass at Santa Rosa Island needed to be monitored. Two Union gunboats blockaded the area, making the Confederates in Pensacola nervous. If the Federal navy could slip through to Union-held Fort Pickens, they could resupply and reinforce the fortification. The Walton Guards began defending “The Narrows”, a shallow inlet between the mainland and Santa Rosa Island. The Walton Guards set up their camp around an Indian midden mound on the mainland side of “The Narrows”, once home to Mississippian natives, and dubbed it Camp Walton. Reddick remembered, “We soon had the camp ground and drill grounds cleared up and set to work building our houses, and in about a week we were all fixed and had a jolly good time.”

In early 1862, a Union landing party threatened Camp Walton, probing for an easy way to get to Fort Pickens. The small engagement at Joe’s Bayou – present day Destin – with forty Confederates pitted against the Union landing crew resulted in two Federal soldiers killed. These deaths brought more focus upon Camp Walton.

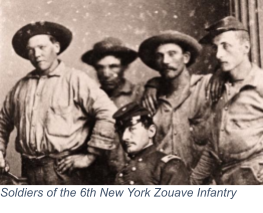

U.S. Brig. Gen. Lewis G. Arnold in command of the US Volunteers in that area issued orders to Capt. Henry W. Closson with a couple of 6th New York Zouave Infantry companies and a battery of artillery to make a reconnaissance in force for “the purpose of ascertaining the character of the upper end of the island and to punish and take prisoners any rebels he might meet, I having received information that about 200 armed rebels were encamped near the Southeast Pass, where they had a few days previously killed 2 sailors and wounded 2 others belonging to the blockading schooner stationed there.”[2]

U.S. Brig. Gen. Lewis G. Arnold in command of the US Volunteers in that area issued orders to Capt. Henry W. Closson with a couple of 6th New York Zouave Infantry companies and a battery of artillery to make a reconnaissance in force for “the purpose of ascertaining the character of the upper end of the island and to punish and take prisoners any rebels he might meet, I having received information that about 200 armed rebels were encamped near the Southeast Pass, where they had a few days previously killed 2 sailors and wounded 2 others belonging to the blockading schooner stationed there.”[2]

Closson set out on March 26, 1862 and reported in his reconnaissance, “In many places, the [Santa Rosa] island is perfectly open, in others screened from the main-land by ridges of sand hills and fringes of forest. The sound is in width from 3 miles to 300 yards, I should judge. The narrowest point is about 40 miles from the fort. Here the rebel camp was located. It is nowhere fordable; navigable for its whole extent for vessels of 7 feet draught, the channel running generally close along the main-land.” The only road existed on the gulf-side of the island and was impassable during high tide. The Federals were afforded the help of Minard Wood. A native of New York City, Wood had formerly worked at a saw mill in Pensacola, “but for the last six months was butler at Gen. Bragg’s headquarters, near the Navy yard having been given his choice to take up arms or be hung. He managed to turn some of the Confederate shiplasters into specie, and leaving his goods behind, crossed to Santa Rosa Island.”[3] Mr. Wood accompanied Lieutenant R.H. Jackson to serve as a guide for the expedition.

Before dawn on April 1, Closson, Company D of the 6th New York and their artillery contingent were in position on the inside beach of Santa Rosa Island, their cannon aimed at Camp Walton. “I remained there until their huts could be seen in the dawn, and then directed Lieutenant Jackson to open fire. The shells burst right in their midst.”

Before dawn on April 1, Closson, Company D of the 6th New York and their artillery contingent were in position on the inside beach of Santa Rosa Island, their cannon aimed at Camp Walton. “I remained there until their huts could be seen in the dawn, and then directed Lieutenant Jackson to open fire. The shells burst right in their midst.”

Reddick, on the receiving end of the bombardment, wrote, “the men were forming in line and answering to their names, when they heard the roar of the gun and heard the shot whistle over their heads.” Reddick himself had been sleeping after a night of picket duty and was woken by one of his messmates at the onset of the attack. “I thought that he was teasing me and while we were talking the second shot came, the ball going through our house near the top and just over my head. There was no more talking. I jumped up and began looking for my pants and shoes, which I had a hard time finding…”

The Walton Guards tried to reform a few times in the hysteria, but Union artillery continually scattered them. Not even Capt. McPherson could rally his men to make a stand against the enemy. Closson reported that, “Loud cries and yells were heard, and the rebels could be barely seen through the brush in their shirt-tails making rapidly into the back country. A scattering volley was fired from what I supposed to be their guard, who then disappeared also.” The Indian midden mound became a refuge for the surprised Confederates. While many of the troops fled to the sheltering woods north of camp, Lt. John L. McKinnon “staid where I could see them all the time I was behind a very large tree & feared no danger.” In his letter to Reverend John Newton on April 2, he said, “After all went out of camp I sent back after a sick man that was behind & I hollered to the Yankees on the island to come over to this side & we would fight them. They said for us to carry over some boats that was on the beach at our Camp & they would. You know we did not comply with this request.”

Closson withdrew and made the journey back to Fort Pickens, satisfied that he had sufficiently harassed the Walton Guards. False reports frightened the Confederates into believing that the Federals had landed around Camp Walton. It was enough to scare them into retreating across Garnier Bayou and trek all the way to Boggy Bayou – present day Valparaiso and Niceville – to stay for three weeks until things cooled off. Bragg gave the Walton Guards orders to immediately return to their former camp and to “hold that place at all hazards.” To help defend the area, the general sent more tents to replace their demolished cabins and two thirty-pound cannons. One was directed at the very spot across the water from which the Federals had assaulted them. Not a single man within the company had ever fired a cannon, nor had been near one when it was fired.

They would have no opportunity to give the cannon a shot. When orders were given for Camp Walton to be abandoned, both cannons were spiked and buried. The Walton Guards marched out of Northwest Florida and became Company D of the 1st Florida Infantry. By 1863, the 1st, 3rd, 4th, 6th, and 7th Florida Infantry regiments were melded into the Florida Brigade. Reddick and the rest of the men would see action at Perryville, Stones River, Chickamauga, and the Atlanta Campaign.

They would have no opportunity to give the cannon a shot. When orders were given for Camp Walton to be abandoned, both cannons were spiked and buried. The Walton Guards marched out of Northwest Florida and became Company D of the 1st Florida Infantry. By 1863, the 1st, 3rd, 4th, 6th, and 7th Florida Infantry regiments were melded into the Florida Brigade. Reddick and the rest of the men would see action at Perryville, Stones River, Chickamauga, and the Atlanta Campaign.

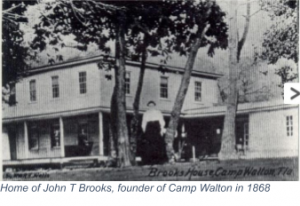

However, this is not the end of the story for Camp Walton. In 1868, a former member of the Walton Guards, John Thomas Brooks, returned to The Narrows with his young wife and homesteaded the very area he had helped defend in the spring of 1862. Eventually, Camp Walton grew into a modest community that played host to travelers from all over. Hotels were built along the waterfront, including near the spot where the Walton Guards were set up. Hotel proprietors rented out boats to their guests to cross The Narrows to Santa Rosa Island. The area that endured Captain Henry Closson’s bombardment was made into Brooks’ Landing, a small park known for its local events.

However, this is not the end of the story for Camp Walton. In 1868, a former member of the Walton Guards, John Thomas Brooks, returned to The Narrows with his young wife and homesteaded the very area he had helped defend in the spring of 1862. Eventually, Camp Walton grew into a modest community that played host to travelers from all over. Hotels were built along the waterfront, including near the spot where the Walton Guards were set up. Hotel proprietors rented out boats to their guests to cross The Narrows to Santa Rosa Island. The area that endured Captain Henry Closson’s bombardment was made into Brooks’ Landing, a small park known for its local events.

In the early 1900s, a discovery was made by W. C. Pryor while digging fence posts for the Indianola Inn – named after the Indian mound. His shovel hit something hard and when the site was excavated, they found one of the thirty-pound cannons that Bragg had given to the Walton Guards. The second is still buried in an unknown location. The unearthed cannon was put on display in front of the Indian midden mound on the sidewalk downtown.

Camp Walton’s population boomed in the subsequent decades and endured much change. In March 1932, the name officially changed from Camp Walton to Fort Walton, a ploy to give more prominence to the place and attract both tourists and prospective citizens. Eglin Air Force Base was established as a training facility north of Fort Walton and the population grew exponentially. The community’s name changed again on June 15, 1953 from Fort Walton to Fort Walton Beach. Casinos, hotels, restaurants, and even amusement parks popped up along Highway 98. The attractions set a reputation as a fun vacation spot, dwarfing its minor historical significance.

Camp Walton is unrecognizable from what it once had been to the ninety-two men who mustered into Confederate service there. But it’s the total evolution of the area that inadvertently helped to preserve its history. Today, the Indian Temple Mound Museum helps to interpret the site of the Native Americans who first called the place home. Because Camp Walton had been originally constructed around the mound, their story is also told to countless visitors. If there had been no explosion in tourism, the cannon may have never been unearthed around the Indianola Inn. Now, it’s on display for pedestrians who come to downtown Fort Walton Beach. What remains of Camp Walton is now a piece of Civil War history at the center of a thriving beach destination.

Camp Walton is unrecognizable from what it once had been to the ninety-two men who mustered into Confederate service there. But it’s the total evolution of the area that inadvertently helped to preserve its history. Today, the Indian Temple Mound Museum helps to interpret the site of the Native Americans who first called the place home. Because Camp Walton had been originally constructed around the mound, their story is also told to countless visitors. If there had been no explosion in tourism, the cannon may have never been unearthed around the Indianola Inn. Now, it’s on display for pedestrians who come to downtown Fort Walton Beach. What remains of Camp Walton is now a piece of Civil War history at the center of a thriving beach destination.

Sheritta Bitikofer is a lifelong student of history with a specific interest in the Civil War era. Along with being a wife, historical fiction author, and fur-mama of two, she is an active member of the Mobile and Pensacola Civil War Roundtables and currently pursuing a bachelors degree in US History at American Public University. She also manages her own modest Civil War blog where she writes about her studies and many travels to battlefields and other historic sites.

Citations:

[1] Reddick, H. W. Seventy-Seven Years in Dixie: the Boys in Gray of 61-65. Santa Rosa Beach, FL: Coastal Heritage Preservation Foundation, 1999.

[2] The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies Volume XV. 1886. (Vol. 15, Chap. 27, pages 499 – 501)

[3] April 21, 1862 The New York Times: Fort Pickens and Key West: Arrival of the Steamer Philadelphia – Quiet at Fort Pickens – Pensacola not Entirely Evacuated – The Rebels Removing Guns and Destroying Property – Martial Law in Pensacola, & c

“History of Fort Walton Beach”; Emerald Coast Magazine; November 26, 2008; https://www.emeraldcoastmagazine.com/history-of-ft-walton-beach; accessed December 1st, 2020

Great historical account! Thanks Sheritta.

Excellent introduction to a neglected “front” of the Secession Crisis: Pensacola Bay and environs. If President Lincoln’s plans had come together, war would have erupted in vicinity of Fort Pickens instead of the isolated fort in Charleston Harbor.

Cheers

Mike Maxwell

Congratulations Sheritta. Great addition to our local history. Keep those posts coming!

Glad to hear from you, Mr. Vickers! I look forward to seeing you whenever the Pensacola CWRT decides to meet up again! Take care!

Thank you this is what keeps history alive

Fascinating Article! Any evidence that the men of the Walton Guards owned slaves, or that slavery was even prevalent in this far western part of Florida?

Over 100 slaves were employed as laborers and shipwrights at Pensacola Navy Yard, with their owners (mostly Pensacola residents) receiving pay from the U.S. Government prior to outbreak of war. Slaves were also essential in construction of Forts Pickens, Barrancas, McRee and the Advanced Redoubt, which defended access to Pensacola Bay. Details contained in Amazon ebook, “The Struggle for Pensacola.”

As Mike said, slavery was definitely present in northwest Florida. I intend to do more research on the subject and have a book about slave accounts from Florida that I haven’t cracked open just yet. Many of the men from the Walton Guard were farmers, but given my own knowledge about the area east of Pensacola where they would have come from, they weren’t planters and likely didn’t own slaves for field labor, but I can’t confirm that for sure. They might have had cooks or house servants. There is no surviving official record of the members of the Walton Guard (no muster rolls, that is) so I can’t drill down into the history of each of the 90-something men very easily at this point.

The disinformation about the Brooks settling the area, not to mention tons of nonsensical stories in Anthony Mennillo’s book needs to be addressed. The Brooks are not listed in any census before 1870, and they certainly weren’t the first to settle nor “found” what is now FWB.

“Early settlers of Walton County, Florida were the first to establish permanent settlements in what is now Fort Walton Beach (the area was originally named “Anderson”). Two of the first settlers were John Anderson and Andrew Alvarez, who received land plots in 1838. The name “Anderson” is noted on maps from 1838 to 1884. It was not until 1911 that the name “Camp Walton” appeared on Florida maps.”

1860 Walton County Slave Schedule is here-

https://genealogytrails.com/fla/walton/1860slave.html