Town Between the Rivers: Cairo, Illinois

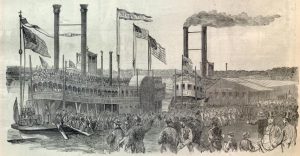

A blue-coated rider appeared atop the riverbank above the steamer Belle Memphis. Rebels massed in the cornfield behind him fired volleys that whistled by the horseman, whanged through the tall smokestacks, and thudded into the vessel’s superstructure. Hundreds of Iowa and Illinois infantry had slithered down the muddy incline and scrambled aboard to escape numerically superior forces threatening to envelop them. The steamer captain pulled in his mooring lines but delayed starting engines; men on deck threw a narrow plank across the water gap.

The rider—a superb equestrian—recalled: “My horse put his fore feet over the bank without hesitation or urging, and with his hind feet well under him, slid down the bank and trotted aboard the boat, twelve or fifteen feet away, over a single gang plank.”[i] Brigadier General Ulysses S. Grant, the last man over, nimbly dismounted and ascended to the upper deck.

A half dozen troop transports opened their steam valves. Smoke billowed and paddlewheels thrashed brown water as they began pulling upstream carrying Grant and his 3,000 men out of danger. Farther out and a bit downstream, Commander Henry Walke, U. S. Navy, observed from the river gunboat Tyler as she and the Lexington threw broadsides into Confederate lines ashore.

“The enemy’s artillery was seen tumbling over, and his ranks were soon broken,” wrote Walke. “They dispersed in the utmost confusion, or fell on the ground to escape our shot and shell.”[ii] Concluded Grant: “We were very soon out of range and went peacefully on our way to Cairo every man feeling that Belmont was a great victory and that he had contributed his share to it.”[iii]

The Battle of Belmont, Missouri, November 7, 1861, on the banks of the Mississippi River was the first major command engagement for the future general in chief. It also was the first significant joint army-navy operation on the rivers. Overseeing his gunboats and transports, Commander Walke rapidly delivered Federal forces to where they were not expected, covered their landing, suppressed enemy batteries on the bluffs of Columbus, Kentucky, across the river, obstructed Rebel reinforcements crossing the stream, scattered attacking gray ranks at the riverbank, and neatly extracted Union fighters when the odds turned. A powerful team melded maritime mobility and firepower with hard fighting on land. But it was a learning process.

The contest for the Lower Mississippi and its tributaries—the spine of America—was one of the longest and most challenging campaigns of the Civil War encompassing over 1,000 twisting river miles (double what the crow would fly) from Cairo, Illinois, to New Orleans cutting through six states in a massive alluvial flood plain averaging 75 miles wide, the best cotton land in the world.

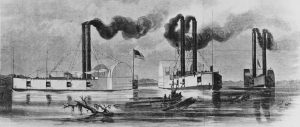

Three months earlier, August 12, 1861, Cairo’s citizens watched from the levee as three odd looking steamboats with extraordinarily tall stacks (“chimneys”), blocky bulwarks, and gaping gunports rounded the Ohio River bend toward them. Westerners had never seen such warcraft, then the only United States naval power on the rivers. The long-awaited Tyler, Lexington, and Conestoga aroused curiosity with skepticism.

These hastily converted side-wheel riverboats, armored all around with 5-inch oak planks to stop rifle bullets, became known somewhat facetiously as “timberclads” in comparison with ironclads that soon followed. Speculation was that they would be sunk by Rebel shore batteries if not shaken to pieces by their own weapons. The timberclads would, nevertheless, see hard and invaluable service.

Cairo lay at the southern tip of the state where clear Ohio River waters flowed in from the east colliding with the turbid Mississippi as she surged on south. The confluence was the most southern point in northern territory, 215 river miles below St. Louis and over 400 river miles west of Cincinnati. Border states occupied the opposite banks, Missouri on the left and Kentucky to the right, almost surrounding the narrow Illinois peninsula. Fifty miles back up the Ohio, the Tennessee River plunged deep into the South while the Cumberland River pointed south and east to Nashville and beyond.

Broad levees extended from this watery junction some three miles up both rivers connected by a third levee enclosing the town in a delta. On the Mississippi side, swift currents scoured low, swampy sandbanks throwing the main channel nearly two miles out toward Missouri. The Ohio, however, flowed serenely by the foot of its levee along whose crest extended Cairo’s main business avenue and behind which wooden staircases lead 14 feet down to the low-lying central district. The St. Charles was the only first-class hotel with two to four beds a room. Sticky mud permeated the streets despite high-volume steam pumps to control seepage.

Cairo (locally pronounced “Kay-ro”) had been named after the exotic city on the Nile following Napoleon Bonaparte’s expedition to the eastern Mediterranean early in the century, which inspired a wave of Egyptomania in Europe and America.

The town became a vortex of river commerce. In 1855, the first train arrived from Chicago over the new Illinois Central Railroad, terminating atop the levee with a depot, warehouses, and railyard. Senate candidate Abraham Lincoln debated Stephen A. Douglas at Jonesboro 30 miles north (September 1858), but he expected little support in this mostly Democratic region known as Little Egypt. By January 1861, Cairo’s population exceeded 2,000. Ten to twenty steamers tied up daily to load and discharge cargo, people, fuel, supplies.

Vast quantities of cotton bales, tons of molasses, sugar, and coffee flowed up the Mississippi to St. Louis, up the Ohio to ports like Louisville and Cincinnati, or down to New Orleans. A single week in March saw almost 20,000 bales of cotton out of Memphis alone. South-bound steamers were loaded down with Northern dry goods, grain, lumber, merchandise, and lead from mines at Galena, Illinois. During the first quarter of the year, over 1,000 tons of produce departed weekly from Cairo to Memphis. On all steamers, passengers thronged the upper decks.

Later in the century, this booming river city continued to host as many as 500 steamboats a month. Opulent Victorians lined the avenues; bars, brothels, and gambling houses along the teeming waterfront catered to steamboat men, merchants, travelers, card sharks, and roustabouts. The scene inspired Edna Ferber’s novel and the musical Showboat. Mark Twain sent Huckleberry Finn and his friend Jim on a raft down the Mississippi to Cairo where they planned to board a steamboat and ride north to ensure Jim’s freedom.

But in the summer of 1861, the town between the rivers was becoming a fortress guarding loyal Illinois to the north, pointing a dagger at the heart of the Confederacy, and throttling traffic on the Mississippi and Ohio—a strategic prize for both sides.

On April 18, five days after Fort Sumter surrendered, Secretary of War Simon Cameron urged Governor Richard Yates to occupy Cairo. Rumors flew of threats by Southern sympathizers to blow up levees or the long wooden steps leading down from them. The mayor deputized 80 loyal citizens.

The governor dispatched by rail from Chicago some 600 untrained and poorly armed militia followed a week later by seven newly raised volunteer companies commanded by Col. Benjamin M. Prentiss and assisted by Capt. John Pope, USA, the first Union forces activated in the west. State and Federal authorities increasingly imposed blockade regulations. Downstream commerce dried up paralyzing the river economy. Triweekly Cairo to New Orleans service ceased.

The Chicago Light Artillery wheeled a fieldpiece aboard the steam tug Swallow guarded by a few Chicago Zouaves creating the first extemporaneous “gunboat,” which kept busy interdicting steamers smuggling contraband—arms, munitions, military supplies—by Cairo.

Thousands of Union soldiers and artillerymen encamped along the river, in a brickyard, and in the fairgrounds. A training camp was established, forts built, and batteries emplaced. Steamy days could be 100° in morning shade; soldiers drilled before 8 a.m. or after 7 p.m.

Lt. Seth Ledyard Phelps, USN, brought his three charges—Tyler, Lexington, and Conestoga—into the embankment on August 12. Phelps reported to the senior naval officer in the west, Commander John Rodgers: “The commanding officer at Cairo was very anxious that the gunboats should make a demonstration down the river toward New Madrid [Missouri], and also be prepared to assist in the defense of Cairo.”[iv] On August 28, General Grant was appointed commander of the new District of Southeast Missouri (which included southern Illinois) and ordered to strengthen Federal defenses along the rivers.

Thus commenced Cairo’s new role as inland naval station and home port for what evolved into the U. S. Navy Mississippi River Squadron—an armada of timberclads, ironclads, tinclads, rams, tugs, transports, and supply vessels. With no land to spare, supporting repair shops, storage sheds, and barracks would line the riverbank on wharf-boats, old steamers, flatboats, and rafts. Naval commanders including Flag Officer Andrew H. Foote, Flag Officer Charles H. Davis, and Admiral David D. Porter developed excellent partnerships with army counterparts, particularly with Generals Grant and Sherman.

It was the beginning of an unprecedented army-navy symbiosis that proceeded through many trials—Forts Henry and Donelson, Shiloh, Island No. 10, Memphis, Vicksburg, Port Hudson, Red River—until Abraham Lincoln could declare: “The father of waters again goes unvexed to the sea.”[v] Cairo, Illinois, the town between the rivers, played a crucial if backwater role in that campaign.

[i] John F. Marszalek, ed., The Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant: The Complete Annotated Edition (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2017), 195.

[ii] H. Walke, Naval Scenes and Reminiscences of the Civil War in the United States, on the Southern and Western Waters During the Years 1861, 1862 and 1863 with the History of that Period (New York: F. R. Reed & Company, 1877), 38.

[iii] Marszalek, ed., Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant, 195.

[iv] Phelps to Rodgers, August 16, 1861, in Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion, 2 series, 29 vols. (Washington, D.C., 1894-1922), series 1, vol. 22, 299.

[v] Abraham Lincoln to James C. Conkling, August 26, 1863, in Merwin Roe, ed., Speeches and Letters of Abraham Lincoln, 1832-1865 (New York: E. P. Dutton & Co, 1907), 222.

References:

Myron J. Smith, The Timberclads in the Civil War: The Lexington, Conestoga, and Tyler on the Western Waters (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 2008).

Shirley Baugher, “Cairo Illinois: Trouble Right Here in River City” (http://www.chicagonow.com/my-kind-of-old-town/2014/07/cairo-illinois-trouble-right-here-in-river-city/, accessed January 2021).

Informative. Engaging. Yet concise as possible. The story of the creation of the Western Rivers Gunboat Flotilla, three timberclads put in place as stopgap while awaiting completion of better armed and better armoured Pook turtles is under-appreciated, but well introduced by Dwight Hughes, here. Especially important: continually improving coordination and superb cooperation with the Navy were among the key strengths of U.S. Grant, arguably leading to his ultimate elevation as Supreme Commander of the Union Army.

Thanks for the nice words Mike. I appreciate the feedback.

Nice post, Dwight! Last year or so, I had the chance to drive through Cairo on a drive back to St. Louis, but it was a mere shadow compared to what it was in its hay day. If you are in the vicinity, make sure you go and just drive through. Lots of beautiful architecture and history. It is just cool to say you’ve been there!

Thanks Kristen! I though you might like it. Sad about the state of Cairo. Wonder if our CW preservation groups could get involved. I’ll need some pictures for the book, so in your travels, please keep an eye out for good ones on the river.

You got it, Dwight! Keep me posted on what you need.

My brother played in a band that performed in Cairo in the 1970’s the owner was crippled due to being shot by The purple gang when Cairo had a lot of mob ties

I stumbled upon this looking for information about a prison camp that was in Cairo at one time. My great-great-great grandfather,, who had recently moved to Illinois from either Kentucky or Tennessee, I can’t remember which one now, was hunting in the woods one day and never came home. When his family went to look for him, they found out he had been taken as a southern sympathizer and thrown in a prison camp that was near the fort in Cairo.He stayed there for a about 2 months before his wife was able to arrange for a lawyer to get him out. He was sick when he got out and they had to hire a wagon to bring him home. He came home and died the next day.. He was about 34.I have been unable to find any information online about this prison camp and was wondering if you might know about it.

Thank you for your question and I apologize for not responding sooner. I do not have information on the prison camp at Cairo, Illinois but will forward the question to my colleagues at Emerging Civil War who have studied the subject of prison camps more closely.

Thank you for your question and I apologize for not responding sooner. I do not have information on the prison camp at Cairo, Illinois but will forward the question to my colleagues at Emerging Civil War who have studied the subject of prison camps more closely.