The William Belknap Impeachment – Some Historical Background

When American author Mark Twain referred to the postbellum United States as living through a ‘Gilded Age’ he almost certainly had in mind the excesses exhibited by men like William Belknap, whose term as Secretary of War in the cabinet of President Ulysses S. Grant ultimately exposed the rot of political cronyism and the failures of postbellum political reform. For his involvement in what is now known as the “trader post scandal,” Belknap was impeached by Congress, after he resigned from his cabinet post, in the first impeachment trial of a private citizen who had left public office.

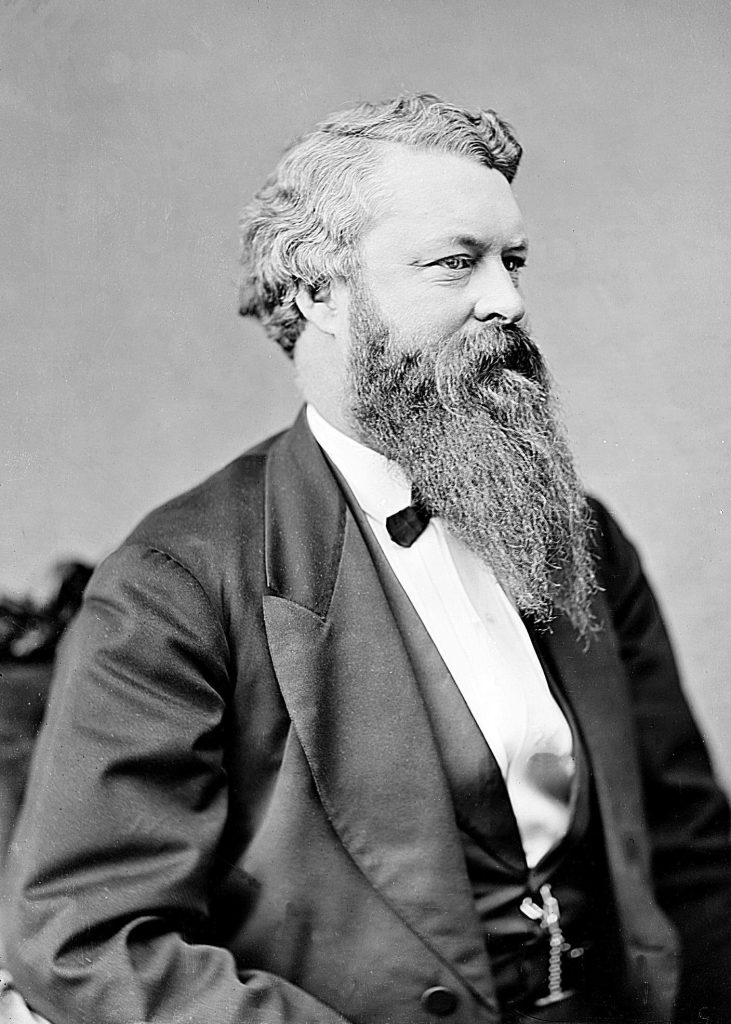

William Worth Belknap was born in 1829 and graduated from Princeton University in 1848. He trained as a lawyer and, in 1851, moved to Iowa, where he served a term in the Iowa House of Representative as a Democrat. At the outset of the Civil War, Belknap received a commission in Fifteenth Iowa Infantry Regiment, fighting at Shiloh and Corinth, and ultimately receiving promotion to brigadier general of volunteers (brevet major general). Belknap changed his political allegiance to the Republican Party in the wake of the Civil War, and was appointed Secretary of War by President Grant in 1869. Belknap succeeded John M. Schofield (a courtesy appointment from the Johnson administration who served less than a year under Grant) and John A. Rawlins, who died of tuberculosis after serving only 7 months.

Upon his appointment, Belknap began to make changes in the War Department, and many of his decisions proved especially galling to the army’s general in chief, William Tecumseh Sherman. Belknap began to make appointments and direct troop movements without consulting Sherman, weakening Sherman’s position and asserting civilian control over the national military establishment. Sherman proved especially unhappy when Belknap slashed the general’s salary in the name of postwar reduction, although Sherman still would be paid more than the Chief Justice and cabinet officers. Belknap’s success in subduing Sherman empowered the secretary to lobby Congress for the sole power to appoint and license sutlers, who received lucrative contracts to establish trading posts at U.S. military installations. Congress granted Belknap’s request, and the secretary stole another longstanding duty from the general in chief. Belknap’s erosion of Sherman’s duties became so egregious that in 1874 Sherman packed up his Washington offices and moved the army’s headquarters to St. Louis, figuring nobody in Washington really needed him to stick around.

In order to maximize profits, Belknap ordered that soldiers posted to western forts could only buy goods and supplies from the sutlers he approved. As he settled into his cabinet post, Belknap soon discovered that his annual salary of $8,000 could not support the lavish lifestyle his wife, Carita, demanded. In search of additional income, Carita engineered the plan that would ultimately bring about Belknap’s downfall. Carita lobbied her husband to appoint a New York contractor, Caleb P. Marsh, to the Fort Sill tradership in what was then Indian Territory (now Oklahoma). Belknap had already appointed an experienced sutler, John S. Evans, who did not want to give up his post. As a compromise, Marsh drew up an illicit partnership contract that allowed Evans to keep the tradership at Fort Sill, provided that he pay Marsh $12,000 per year in quarterly installments. Marsh, in turn, was required to give half of his $12,000 to Carita, also in quarterly installments. Carita died in December 1870, after receiving only one payment. After her death, her sister, Amanda, continued to accept payments from March—with Belknap’s full knowledge and approval of the scheme. Belknap married Amanda in 1873.

In February 1876, word reached the House of Representative that Belknap had been accepting kickbacks from traderships on western posts. Pennsylvania Democrat Hiester Clymer launched an investigation into the War Department. Clymer’s sense of justice was fueled, in part, by seeking revenge against the Radical Republicans, whom he believed had misused the army in upholding marshal law in the South during Reconstruction. Caleb P. Marsh testified to the Clymer Committee that Belknap had personally taken payments as part of the partnership agreement between Marsh and John S. Evans. On March 2, while eating his breakfast, President Grant received a warning that the House intended to bring impeachment charges against Belknap—and by 10:20 that morning, Belknap had tendered, and Grant had accepted, his resignation. When the Clymer committee received word of the resignation, the members unanimously passed a resolution to impeach Belknap—claiming it was obvious that he had only resigned to escape impeachment, and that this fact should not prevent the government from holding him responsible for his corruption. At the time of the events, no constitutional precedent existed for impeaching a former government official who had reentered civilian life.

At the end of March Lieutenant Colonel George A. Custer appeared in Washington to give testimony about his intimate knowledge of the “Indian ring” that Belknap had operated. If Custer’s goal was to create a public spectacle (it often was), he certainly succeeded. For good measure, Custer accused not only Belknap, but also President Grant’s brother, Orvil, of being involved in the trader post scandal. On the back of Custer’s testimony, the Senate launched an impeachment trial, after a vote of 37-29 that affirmed that the upper chamber had the constitutional prerogative to try a resigned government official. The majority based their decision on the constitutional provision that judgment in cases of impeachment provides not only for removal from office but also for disqualification to hold any office of honor, trust or profit under the United States. Belknap’s defense team insisted throughout the trial that such authority did not exist.

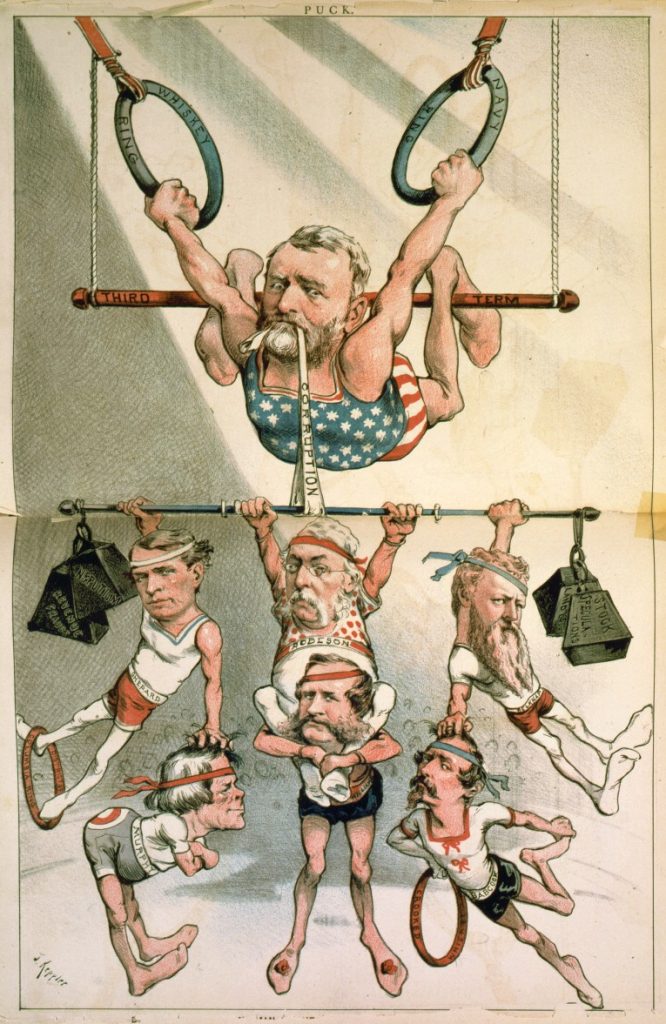

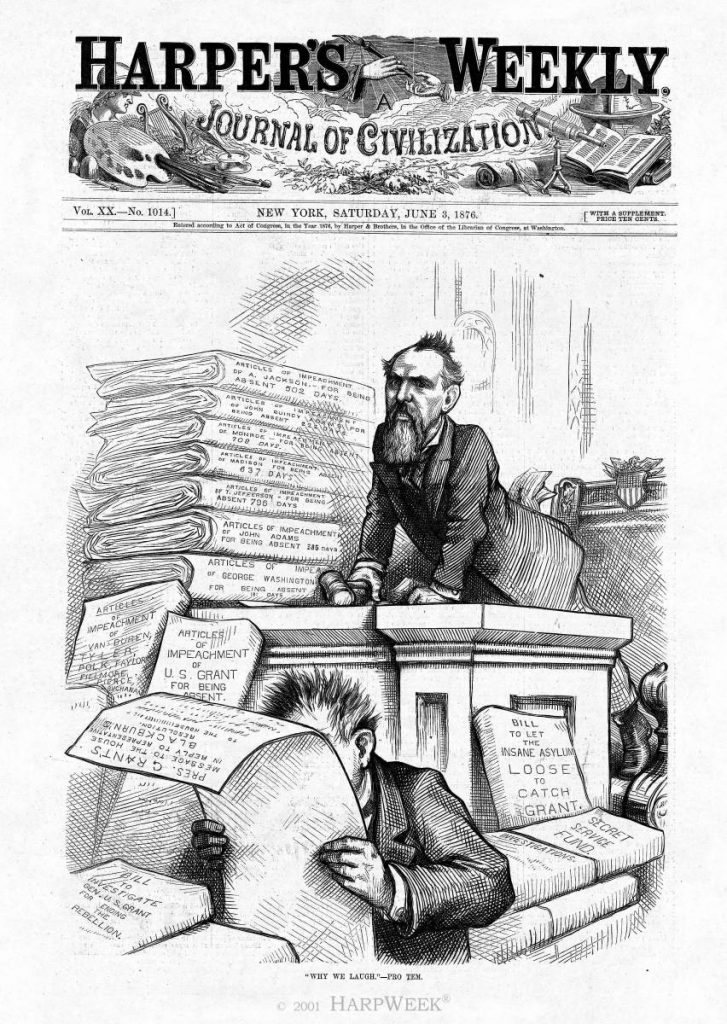

At the time of the Belknap trial, Democrats in both houses of Congress were engaged in an effort to root out Republican corruption and expose the scandals of the Grant administration to the public–in the advance of that fall’s presidential election. The Belknap scandal followed in long line of Grant missteps, including the Whiskey Ring, and most famously, the Crédit Mobilier scandal. Though Belknap was guilty of taking bribes and of corruption, the clearly partisan nature of the trial caused the popular media to mock the event as a circus. A Thomas Nast cover for Harper’s Weekly lampooned the idea of impeaching resigned officials by presenting impeachment charges for multiple presidents who had long since left office, as the scuttlebutt in Washington had begun to suggest that if the Democrats couldn’t get Belknap they would try for Grant instead.

The Senate heard testimony from some 40 witnesses in the Belknap case—and the trial stretched through the languid summer of 1876, interrupted by news of the death of Lieutenant Colonel Custer and his troopers at the Little Bighorn (in the historiography of the battle some early writers claimed that Belknap’s post traders sold superior weapons to the Native Americans than Belknap supplied to the army, which sent Custer and his men into battle at the Little Bighorn that June with breechloaders that jammed after the third round, while the Lakota and Cheyenne opposition fought with better breechloaders and some 300 repeating rifles). On August 1, with 40 votes needed for conviction, the Senate voted 35 to 25 to convict Belknap, with one Senator not voting, thus acquitting Belknap of all charges by failing to reach the required two-thirds majority. All Senators agreed that Belknap took the money from Marsh, but 23 who voted for acquittal believed that the Senate did not have jurisdiction to try a resigned government official. Ultimately, the speed with which Ulysses S. Grant accepted Belknap’s resignation saved the disgraced secretary from conviction.

As it played out, the trial became less about whether Belknap had committed high crimes and misdemeanors more about the constitutional issue of impeachment and the purpose and extent of Article II. In some ways, the Belknap case is instructive for the current moment, but in others it presented the Senate with a very different problem–Belknap had made money from abusing his cabinet post, but he was not the president, or the vice president, or, indeed, an elected official of any kind. As is almost always case, turning to history for instruction almost always complicates the picture of the present. Long forgotten, the Belknap case is reminder that there is almost nothing new in history.

Belknap was acquitted. Had he not been, he would have sued for the unconstitutional use of the impeachment process.

He might have sued, but there’s nothing to suggest how the Supreme Court would have ruled, so it’s not accurate to characterize the the use of the impeachment process as “unconstitutional.” “Alleged unconstitutional” would be accurate.

Allegedly/Arguably/Maybe constitutional would also have to be used then too… to be accurate.

The Constitution suggests an answer though and it must.

“23 who voted for acquittal believed that the Senate did not have jurisdiction to try a resigned government official.” And we know this how? Were they polled? Did they join in a letter to the Times?

Hello! Thanks for your question. We do actually know the reason for the acquittal, because the vote was preserved in the Congressional Record and the Report of the House Managers on the impeachment trial:

From the Congressional Record (44th Congress), pp. 5082, 5083.

“That the defendant, William W. Belknap, has been acquitted on all the articles presented against him, less than two-thirds of the Senators present voting ‘‘guilty.’’ The final vote was 61; 37 of the Senators voted ‘‘guilty,’’ 23 ‘‘not guilty for want of jurisdiction,’’ 1 ‘‘not guilty.” A change of 5 votes would have resulted in the conviction of the defendant by the two-thirds vote required by the Constitution.”

23 senators voted not guilty for want of jurisdiction, in other words, because they believed they could not convict someone who was not a government official at the time of the trial.

Interesting. You really cannot fault Belknap for seeking to impose civilian control over the military. But the self dealing was outrageous!

“But the self dealing was outrageous!”

LOL. The Politicians and bureaucrats in DC do this all the time. It’s how the senators and representatives are elected with little money but retire as millionaires.

If the Senate has “sole power” I don’t see how that is reviewable.

Too bad they didnt convict, he could have taken it to the SCOTUS so a ruling would have been made on the Constitutionality of impeachment of a non govt official. Possibly keeping us from the current circus going on now

Great article! Intriguing details about Sherman and Custer. Did anyone ever go after Belknap in a criminal court?