A Poet’s Perspective: Melville on Running the Batteries at Vicksburg

It was the spring of 1863, Union Gen. Ulysses S. Grant was concocting a plan to seize the city of Vicksburg, Mississippi. As President Abraham Lincoln had made clear, Vicksburg was key to achieving victory over the Confederates and ending the war.

With help from Admiral David Dixon Porter, Grant launched a plan that in modern terms could be described as a “Hail Mary” in the fourth quarter with one final chance to score. The plan required Porter and his fleet to navigate a miles-long stretch of the Mississippi controlled by the Confederates. Porter made his pass on April 16, 1863.

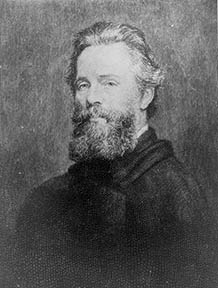

The scene as described by poet Herman Melville:

A moonless night–a friendly one;

A haze dimmed the shadowy shore

As the first lampless boat slid silent on;

Hist! and we spake no more;

We but pointed, and stilly, to what we saw.

We felt the dew, and seemed to feel

The secret like a burden laid.

The first boat melts; and a second keel

Is blent with the foliaged shade–

Their midnight rounds have the rebel officers made?

Unspied as yet. A third–a fourth–

Gun-boat and transport in Indian file

Upon the war-path, smooth from the North;

But the watch may they hope to beguile?

The manned river-batteries stretch for mile on mile.

Porter’s primary objective was to ferry supplies to Federal troops stationed at New Carthage, Louisiana, and then to bring those troops to the east bank of the Mississippi. To accomplish this, Porter’s ships would have to sneak past the Confederate river batteries at Vicksburg. Failure would mean the destruction of Porter’s squadron, his career, and possibly his life.

Porter set sail with seven ironclad gunboats and three transport ships, ordering his men to extinguish all lights and cover all ports until the vessels were close enough to open fire on the enemy. “Before starting, the hour of departure will be given, and every vessel will have her fires well ignited, so that they will show as little smoke as possible,” said Porter.

The plan seemed to be working until Porter’s fleet rounded Point De Soto—when all of a sudden the enemy troops began lighting fires to illuminate the passing ships.

Melville wrote of this terrifying moment in his poem:

A flame leaps out; they are seen;

Another and another gun roars;

We tell the course of the boats through the screen

By each further fort that pours,

And we guess how they jump from their beds on those shrouded shores.

Converging fires. We speak, though low:

“That blastful furnace can they thread”

“Why, Shadrach, Meshach, and Abed-nego

Came out all right, we read;

The Lord, be sure, he helps his people, Ned.”

How we strain our gaze. On bluffs they shun

A golden growing flame appears–

Confirms to a silvery steadfast one:

“The town is afire!” crows Hugh: “three cheers”

Lot stops his mouth: “Nay, lad, better three tears.”

A purposed light; it shows our fleet;

Yet a little late in its searching ray,

So far and strong, that in phantom cheat

Lank on the deck our shadows lay;

The shining flag-ship stings their guns to furious play.

Porter’s fleet became more vulnerable with each torch that appeared on the bluffs, and it didn’t take long for the Confederates to open fire. Porter’s ships took shelter against the riverbank, but every single ship was struck at least once. It is estimated that the Confederates fired more than 500 rounds into the fleet. Here’s the action as described by Melville:

How dread to mark her near the glare

And glade of death the beacon throws

Athwart the racing waters there;

One by one each plainer grows,

Then speeds a blazoned target to our gladdened foes.

The impartial cresset lights as well

The fixed forts to the boats that run;

And, plunged from the ports, their answers swell

Back to each fortress dun:

Ponderous words speaks every monster gun.

Fearless they flash through gates of flame,

The salamanders hard to hit,

Though vivid shows each bulky frame;

And never the batteries intermit,

Nor the boats huge guns; they fire and flit.

Anon a lull. The beacon dies:

“Are they out of that strait accurst”

But other flames now dawning rise,

Not mellowly brilliant like the first,

But rolled in smoke, whose whitish volumes burst

Though bruised and battered, most of Porter’s ships made it successfully through the gauntlet. One transport ship wasn’t so lucky, having caught fire when a shell struck a bale of hay.

A baleful brand, a hurrying torch

Whereby anew the boats are seen—

A burning transport all alurch!

Breathless we gaze; yet still we glean

Glimpses of beauty as we eager lean.

The effulgence takes an amber glow

Which bathes the hill-side villas far;

Affrighted ladies mark the show

Painting the pale magnolia–

The fair, false, Circe light of cruel War.

The barge drifts doomed, a plague-struck one.

Shoreward in yawls the sailors fly.

But the gauntlet now is nearly run,

The spleenful forts by fits reply,

And the burning boat dies down in morning’s sky.

All out of range. Adieu, Messieurs!

Jeers, as it speeds, our parting gun.

So burst we through their barriers

And menaces every one:

So Porter proves himself a brave man’s son.

Porter’s flight down the Mississippi took less than three hours but had a permanent impact on the Union’s position. And, despite the heavy shelling, not a single life was lost. All sailors aboard the destroyed transport ship were relocated to nearby vessels. Thanks to Porter’s bravery, General Grant was now in a position to launch a ground assault against the fortifications at Vicksburg. The first objective was to move his men across the Mississippi, an effort that would lead to more fighting.

It began in Grand Gulf, Mississippi. On April 29, seven Union ironclads opened fire on Fort Wade and Fort Cobun, using their massive guns to blow holes in the riverside defenses. Fort Wade suffered a direct hit, exploding into flames before 10:00 a.m. Fort Cobun retaliated by targeting the USS Benton—Porter’s flagship in the run at Vicksburg—and successfully handicapped the ship by destroying its wheel. Porter himself was struck in the head by a shell fragment, causing an injury that forced him to start using his sword as a cane.

All told, Union forces suffered a total of 75 casualties (18 dead, 57 wounded) while Confederate forces suffered 22 casualties (3 dead, 19 wounded). The USS Benton and the USS Tuscumbia suffered significant damage but were able to remain with the fleet.

At this point Porter and Grant abandoned their plans to make an amphibious landing at Grand Gulf. Instead, they launched a second attack on Fort Cobun to distract the Confederates while the transport vessels continued south towards New Carthage and made a successful landing at Bruinsburg, Mississippi. Following the landing, Federal troops had a three-week march east to Vicksburg, a journey that placed them in enemy territory without a strong supply route.

When they arrived, it was clear that Vicksburg would not be taken with brute force and Grant would have to “out-camp” the enemy by blocking supply routes. As Grant stated, “I now determined upon a regular siege—to ‘out-camp the enemy,’ as it were, and to incur no more losses.” With Grant’s forces camped outside the city and Porter’s squadron maintaining a blockade along the river, no supplies would reach the Rebels at Vicksburg and the town would slowly starve to death.

The plan worked and Vicksburg surrendered to the Union on July 4, 1863. Just a day earlier, Gen. Robert E. Lee was defeated at Gettysburg, making the defeat at Vicksburg a double blow to the Confederacy and pushing the Union closer to winning the war.