On The Eve Of War: Los Angeles, California

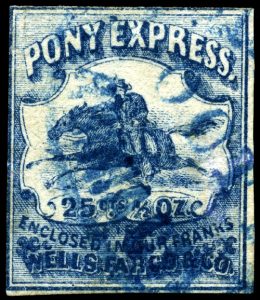

On April 24, 1861, a Pony Express Rider carried the news into San Francisco, California: Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor, South Carolina had been fired upon. The account was not unexpected and released a flurry of activity along the coast and through the inland communities of the Golden State.

Los Angeles, a growing port in the southern side of the state, faced a particular crisis. The southern portion of the state had significant sympathies for the Confederacy. Talk swirled about dividing California, with the northern half staying loyal to the Union and the southern half joining the Confederate cause.

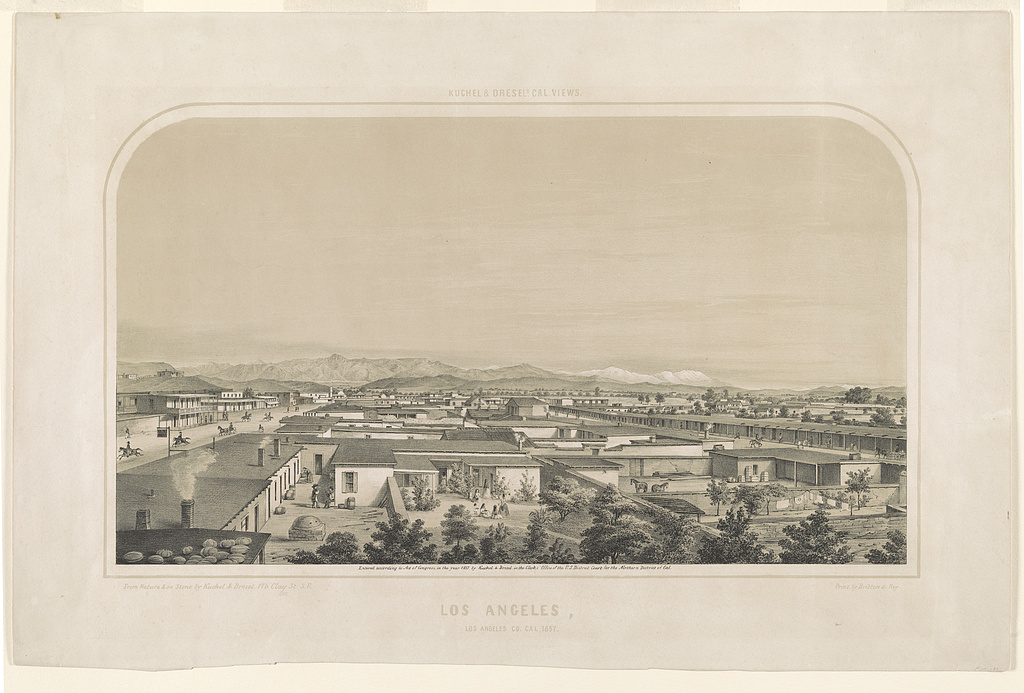

The Los Angeles of 1861 was vastly different from the sprawling urban center of the 21st Century. Mrs. Hancock, wife of Captain Winfield S. Hancock who was stationed in the town, gave a glimpse of the scene in her writings, recalling: “then it boasted of 4,000 [residents]. Its main street was lined on both sides with adobe houses of true Spanish type, and not very many of them; but the surrounding country, with its beautiful hills and valley, its snow-capped mountains and variegated fields, was unsurpassingly charming.” The majority of the citizens were of Spanish or Mexican descent, practicing Catholicism. Some Native Americans had assimilated into the local community while others preferred to live with their tribes and visited the Hancock’s home and quartermaster depot on forced diplomatic endeavors.

The Los Angeles Star—a notoriously pro-Confederate newspaper—fanned the flames of dissention, declaring that the “Black Republican” Party had only a demand for “blood, blood” while the Southern States “asked for peace.”[i] This publication tapped into the sectional conflicts and sectional interpretations of the U.S. Constitution which favored secession over perpetual union. The editor of the Los Angeles Star, Henry Hamilton, encouraged others to follow his secessionist views and since the majority of U.S. citizens in the Los Angeles, San Bernardino, Riverside, and San Diego areas had immigrated from slave-holding states, his opinions aligned and influenced the thought patterns.

Around the autumn of 1860, the “Bear Flag” had been seen in the outlying communities of Los Angeles. This symbol of rebellion was uniquely Californian and dated back to the Bear Flag Revolt in 1846 when groups of Americans living in California rebelled and informed the Mexican government that they were claiming the territory for the United States. The Bear Flag Revolters elected John C. Fremont to lead “The Republic of California” and seized important towns without much resistance, paved the way for California to join the union which it did as a free-soil state in 1850. The flag of the 1846 revolt featured the silhouette of a grizzly, a star, and a red stripe—forming inspiration for the state flag adopted and used to this day.

However, the “Bear Flag” paraded in 1860 and 1861 was a gesture of defiance to Federal authority, and with talk from the state governor and legislature about reverting to an independent republic or splitting the state, the U.S. officers and federal representatives in the region were understandably nervous. Mrs. Hancock recalled:

“The Spanish element was in entire sympathy with the project to establish an independent Pacific republic, and it was understood that they had actually raised the ‘Bear’ flag in one of the adjacent towns. The Spaniards in that region indicated their desire for war in a novel way, and by an old and time-honored custom, as I afterwards learned. Eight or twelve horsemen in full regalia would form a line, riding slowly past the offender’s house (in this case the offender being Mr. Hancock, as the representative of the United States Government), with heads turned in a menacing manner. I enjoyed the spectacle until warned of its significance as indicative of future mischief.”[ii]

The news of Sumter arriving toward the end of April 1861 set of a chain of events in the military department. First, Albert S. Johnston was removed from command of the Pacific Department and Edwin V. Sumner took over. Second, commanders of military establishments were ordered to hold their posts.

In Los Angeles itself, Captain Winfield S. Hancock commanded a so-called “fort” and oversaw the quartermaster depot. Determined to hold the town and small military establishment for the Union, Hancock nervously waited for troops to arrive. Meanwhile, he stayed in contact and on moderately friendly terms with his pro-secessionist civilian neighbors. According to his wife, Hancock also “began his preparations for defense, by concealing the boxes of arms and ammunition under innumerable bags of grain, and in addition, placing his wagons in such a position as to improvise a quite formidable barricade, behind which he intended to contest every foot of ground, aided by the few loyal friends who promised their support, at a given signal, in case of emergency. Fearing a personal assault upon himself, a very possible event, as he was the only United States official within a hundred miles of Los Angeles he collected a small arsenal of twenty Derringers within his own house, in readiness for use at a moment’s notice, relying upon my assistance to prevent his capture, should the attempt be made. I was at the time a pretty good shot…and I felt quite equal to the confidence reposed in me.”[iii]

Following orders at the end of April 1861, Captain Hancock made preparations to close Fort Mojave miles to the east along the Colorado River (California/Arizona border), consolidating resources at Los Angeles. He also knew there were orders for more troops to arrive from Fort Tejon—located in the mountains to the northeast of Los Angeles—to form a defensive camp. By May 4, 1861, Hancock anxiously wrote to Sumner: “if there is trouble here, I will be able to defend the public property with the supporters of the Federal Government to be had on my call from among the citizens of Los Angeles.”[iv] Days later, he reported that, in addition to his defensive barricades, preparations had been completed for the new military camp at Los Angeles and that he awaited the arrival of the dragoons from Fort Tejon.

Hancock expressed the opinion that, though many of the Los Angeles residents and residents on the ranches and in other small towns in the area supported secession, he believed they would not risk an outright fight since they were “men of property,” likely to lose much by outright rebellion. That didn’t mean there wouldn’t been a sneaky, sabotaging action to break up the military camp before it was occupied or destroy the supply depot, though.

Through his network of contacts, Hancock heard that May 12 would likely be the day of a “demonstration” in the streets of Los Angeles in favor of the Confederacy. The dragoons had still not arrived. After a tense day resulted in no significant action, the quartermaster captain reported: “There was no trouble here whatever today…. Those intending to parade…thought better of it….[and] found that they were being compromised in an affair for which they were not prepared.”[v]

By May 25, the dragoons had arrived, and Hancock—joined by Union-supporting citizens—hosted a parade of his own through the streets of Los Angeles, symbolizing the city secured for the Union. As the prominent town in the southern California region, Hancock’s calm, decisive preparations had kept the peace and secured the city and counties to stay within the state and within the Union. Captain Hancock and his family returned east later in the year, upon the receipt of transfer orders received on August 3, 1861.

Meanwhile in 1862, the temporary camp Hancock had set up at Los Angeles moved location to modern-day Wilmington (still near Los Angeles and protecting the port) and became Drum Barracks, a military post sending cavalrymen into the frontier western territories during the war period.

As for the fiery editor of the Los Angeles Star, in 1862, Hamilton faced suppression of his printed opinions and a charge of treason for his open support of the Confederacy, leading to further conflict and debate over a citizen’s rights to free speech in time of war. Another incident around the same time prompted military scrutiny in the Los Angeles area. A group of Southern supporters brought a portrait of General Beauregard into town and supposedly publicly announced their allegiance to the Confederacy. General Wright, the new commander in the region, responded promptly with General Order No. 17, allowing for arrests on the charges of treasonous activities.

Although the Civil War years passed without extreme violence in Los Angeles and Southern California, it was not without debate and conflict. However, the prompt actions in Los Angeles “on the eve of war” and in the early days of the known conflict resulted in a more tranquil scene—one very different from the partisan and vigilante scenes that Captain Hancock had feared and prepared for in early 1861 when the “Bear Flag” was raised in defiance of the Federal government in the green-golden spring hills of southern California.

Sources:

[i] Los Angeles Star, May 11, 1861: National Affairs Column. Accessed through Newspapers.com – https://www.newspapers.com/image/689606070/?terms=war&match=1

[ii] Almira Russell Hancock. Reminiscences of Winfield Scott Hancock. (New York: Charles L. Webster & Co., 1887). Page 59

[iii] Ibid., Page 60.

[iv] David M. Jordan. Winfield Scott Hancock: A Soldier’s Life. (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1988.) Page 32.

[v] Ibid., Page 32.