In the Footsteps of the 130th Pennsylvania at Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville

The 130th Pennsylvania Infantry mustered in for a nine-month term, serving from August 1862 to May 1863. During this comparatively brief time, they fought in some of the war’s bloodiest battles. In a previous post, I followed in the footsteps of my ancestor, Jacob Reever, and the 130th Pennsylvania during the battle of Antietam. After burying the dead in the aftermath of that battle and a short stay in Harpers Ferry, the regiment’s next trial by fire was the battle of Fredericksburg. Their next attack on a road lane fortified by Confederates was far more difficult than when they attacked the Sunken Road at Antietam a few months prior, and this post continues their story by tracking the regiment through their other two major combat experiences: Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville.

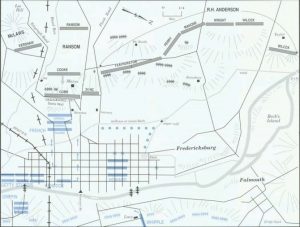

It is difficult to follow Union regiments at Fredericksburg if they were involved in assaults on the Sunken Road, especially since much of the field has now been developed into a housing subdivision. The Third Division of the Second Corps, commanded by Major General William French, was the first to assault the imposing position. Brigadier General Nathan Kimball’s brigade led the division directly into hell. Another brigade under Colonel John Andrews was sent to support Kimball when the assault stalled. Colonel Oliver Palmer’s brigade, containing the 14th Connecticut, 130th Pennsylvania, and 108th New York, was thrown in next to support Andrews. Following their comrades, Palmer and the 130th fixed bayonets, moved down Princess Anne Street, turned to Prussia Street, and crossed the millrace, coming under heavy artillery fire. The brigade staggered at the millrace, briefly losing order. One Pennsylvanian described this terrain as a “most serious and embarrassing obstacle, and very disconcerting under a raking storm of projectiles.”[1] Andrews’ brigade moved forward, and when they were shattered it was Palmer’s turn to advance into the hellish terrain before them.

Reaching the swale, the men of the 130th Pennsylvania were now under fire from both canister and infantry fire. Their brigade pushed into the fairgrounds, halting in the middle of an open space when they were unable to move further. This halt without cover proved costly. Beloved commander Colonel Henry Zinn, whose face adorns the regimental monument at Antietam, grabbed the regimental colors and tried to rally his men, crying out “Stick to your standard, boys! The One Hundred and Thirtieth never abandons its colors; give them another volley!”[2] Zinn was almost immediately killed. As Major John Lee had been wounded, command fell to Captain William Porter who withdrew the remnants of the regiment to the edge of the fairgrounds, where they lay down near other Union infantry. With no hope for success and dwindling ammunition, Palmer’s brigade limped back toward town in scattered groups or remained across the killing field or near the millrace. As Major General Winfield Scott Hancock’s division entered the field to continue the attack, French had ordered his own division, the 130th Pennsylvania included, off the field. Though many wounded may have remained in the fairgrounds, this was the end of the regiment’s battle.

Following disastrous defeat at Fredericksburg, the 130th Pennsylvania eventually retreated across the river and went into winter encampment. Come the spring, they marched yet again toward combat. However, their enthusiasm was not as high as it once was, a situation that plagued many in the Army of the Potomac. Following brutal combat experiences at Antietam and Fredericksburg, it is easy to imagine that many were disillusioned of any previous ideas they had about the glory of military service. In addition, some soldiers of the regiment were beginning to argue that their enlistments had ended. In August 1862 they had enlisted for nine months, and some soldiers believed their terms were over. A Corporal of the 14th Connecticut, brigaded with the 130th, wrote home on April 25, 1863 that many he spoke with thought their service was over “on Wednesday next and if they don’t feel happy then I don’t know what it is to be happy.”[3] However, the War Department’s terms decreed the regiment had to serve another month. It is likely that this discrepancy stemmed from soldiers counting the nine months from the day of their enlistment, while the War Department counted the mustering of the entire regiment as the beginning of service.

Crossing United States Ford on April 30th, the U.S. army moved into position near Chancellorsville. The following day the 130th Pennsylvania moved west of the Chancellor house, preparing a defensive position looking further westward. On May 2, Lieutenant General Thomas Jackson’s troops slammed into the Union Eleventh Corps in a massive flank attack, and the 130th Pennsylvania would soon be engaged in an attempt to stem the Confederate tide. As routed troops streamed past them, their brigade, now commanded by Brigadier General William Hays, repositioned. Reever’s Company K was the left of the regiment, along the Orange Plank Road, where the overcast sky, dense woods, and shady night was interrupted by bright gunfire and was noted by one soldier as “the most frightful and terrible night I ever experienced and the horror of the scene defies even an approximate description.”[4] That evening they checked the assault, and were only a couple hundred yards away from where Jackson was mortally wounded by his own men.[5] Fighting resumed the next morning, and other Union units pushed beyond the 130th to form an advanced line.

My fourth-great grandfather left very little documentary evidence of his service, but he appears at this moment in the 1904 memoir of Edward Spangler, a fellow York County resident also serving in Company K. Since other Union troops had moved ahead of them, the 130th Pennsylvania was unable to join in the increasingly intense fight. Written years after Reever’s death, Spangler recalls: “As we could not fire over the heads of these intervening troops, and our regiment thus temporarily inactive, Jacob G. Reever and I became so impatient as well as excited at the gallant fight on the left of our comrades in the clearing, that we started to leave our company to join in the struggle, but were called back by our Captain, much to our regret.”[6] Apparently, Spangler and Reever were not too disillusioned by what many considered an extended term of service and were eager to continue fighting, seeking an opportunity when the regiment’s position limited the ability to fire. Soon, however, the advance troops were defeated and the 130th Pennsylvania did not last much longer. The brigade was overwhelmed and thrown back, and Hays and much of his staff were captured by the Confederate onslaught. The entire U.S. line in this region was now in retreat, falling back as much of the woods around them caught fire. That afternoon the regiment rallied near the Bullock Clearing but remained out of the action. In the early morning of May 6 they began a retreat back across the pontoons at United States Ford, returning towards their winter camp.

The 130th Pennsylvania’s term of service expired on May 12, and they were sent to Harrisburg, Pennsylvania to be mustered out on May 21, 1863. The men returned to their homes across the state, and Spangler and Reever were among those returning to York. The town received these battle-tried veterans with a warm reception that included ringing bells, a procession, and food.[7] In the decades after, their veteran organization met often, allowing these men to gather and recall what they experienced together at Antietam, Fredericksburg, and Chancellorsville, as well as during all the days and months between. Possibly influenced by proximity to home, Antietam became a popular reunion destination. Though that battle, their trial by fire a mere month after mustering in, became their defining moment in service as they looked back, their experiences at Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville were similarly chaotic and deadly. These three battles, as well as all their experiences in camp and on campaign, prove that the 130th Pennsylvania’s comparatively brief wartime experiences were nevertheless quite trying.

[1] Edward W. Spangler, My Little War Experience with Historical Sketches and Memorabilia (York, PA: York Daily Publishing Company, 1904), 65.

[2] Francis Augustin O’Reilly, The Fredericksburg Campaign: Winter War on the Rappahannock (Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press), 268-269.

[3] Stephen W. Sears, Chancellorsville (Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1996), 133.

[4] Spangler, 92.

[5] Terrence W. Beltz, “The History of the One Hundred and Thirtieth Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry” University of Richmond Master’s Theses, 144-145.

[6] Spangler, 110.

[7] Spangler, 124-129.

The 130 th Pennsylvania’s battle flag with these 3 battles listed would have caught the respectful attention of their fellow combatants

Nice post, Jon. My great grandfather (Pvt. John K. Bupp) was in Company K of the 130th PA.

Thanks Mark. Glad to connect with another descendant of the same company! Small world. Be sure to catch my other two posts on the 130th.

Jon: Please contact me as I had two great uncles in Co. K, the Raffensberger brothers, Edward and Daniel. I also wis to discuss the event of the evening of the first night at Chancellorsville, regarding Lt. John Hays. Ron Bupp (my dad’s name was John Bupp, most likely related to the Bupp on the post above), Ron Bupp

Jon: Please contact me as I had two great uncles in Co. K, the Raffensberger brothers, Edward and Daniel. I also wis to discuss the event of the evening of the first night at Chancellorsville, regarding Lt. John Hays. Ron Bupp (my dad’s name was John Bupp, most likely related to the Bupp on the post above), Ron Bupp

Ron,

Wow, always nice to hear about more Company K descendants.

If you go ahead and send a message to our “Contact Us” page at https://emergingcivilwar.com/contact-us/, they’ll relay it to me and we can chat further.

Jon