Raising the Regiment: Die Neuner

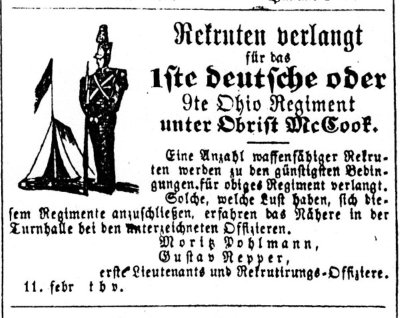

Cincinnati’s German American community responded to the news of the surrender of Ft. Sumter and President Lincoln’s call for troops with unbridled enthusiasm. Handbills posted the evening of April 14, 1861 on the wall at Turner Hall on Walnut Street included a signup sheet for volunteers. Hundreds enlisted that same evening. Gustav Tafel, leader of the local Turner Society, and August Willich, founder of Cincinnati’s German Workingmen’s Society held rallies that week and recruited four companies each. In no time, the ranks of the Ninth Volunteer Infantry, Ohio’s first all-German regiment, overflowed far past the 1000-man target. This was hardly surprising to anyone who lived in the Over-the-Rhine neighborhood where most recent Germanic immigrants resided. Most of these men anticipated war against the still-forming Confederate States and had been conducting military exercises for months.[1]

Lincoln had visited Cincinnati on February 12 as part of a whistle-stop tour to thank political supporters on the way to his inauguration. Willich, editor of the Cincinnati Republikaner, greeted the president with a speech printed that morning in his newspaper and delivered orally that evening amid flambeaux torches outside Lincoln’s hotel. With war looming on the near horizon, Willich pledged his support. “If to this end you should be in need of men, the German free workingmen, with others, will rise as one man to your Call, ready to risk their lives in the effort to maintain the victory already won over slavery.” [2]

The new recruits stood out from their native-born counterparts as nearly all had some degree of military training in the private rifles companies and militias organized by Willich and Tafel. The Ninth’s soldiers were, on average, two years older than a typical volunteer and all ten company captains had seen combat in Europe. Their physical fitness, particularly among the Turners, was so formidable that examining physicians called them “as solid as heart pine and supple as antelopes.” When doctors thumped their chests, “it sounded like so many anvils.” Their residence in close quarters amid large urban populations meant that they were more resistant to disease than many volunteers who enlisted from rural areas. These advantages helped the Ninth Ohio become a disciplined and highly effective fighting force. [3]

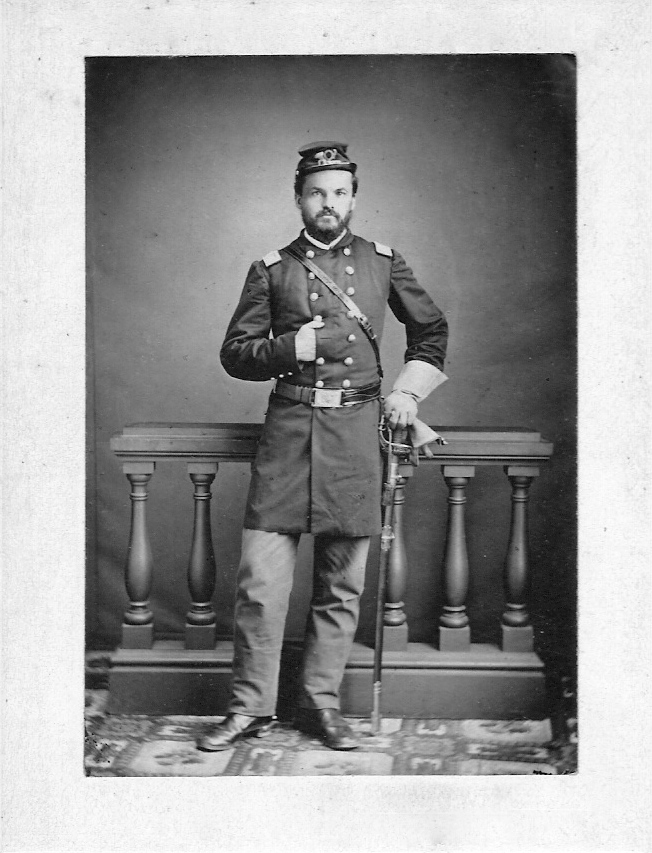

As the Ninth began drilling, other regiments, local press, and onlookers noticed how quickly these Germans became an elite regiment. More than 300 men who had originally enlisted were weeded out by late April and replaced by more fit recruits. When two Turners arrived from Lexington, Kentucky seeking to join the Ninth, they were told that the regiment was full. When he heard one of them remark that they would try to enlist in the Sixth Ohio, Willich challenged them. “See that fence? Jump it!” The men vaulted the fence with ease, over and back. Willich assured them that they would be accepted. Although the former Prussian lieutenant was the best-trained and most experienced leader in the regiment and had personally recruited nearly half of its soldiers, he was not elected its colonel. That honor fell to Robert McCook, law partner of local German American leader Johann Stallo. McCook had important political connections on Washington D.C. which proved vital in ensuring that his regiment would receive arms and supplies quickly. McCook described his role as “merely the clerk to a thousand Dutchmen.” Fifty-year-old adjutant Willich conducted drills and became the father figure of the regiment.[4]

Willich trained his troops using the Prussian drill manual. Commands were given in German, using bugle signals. The regiment operated as two battalions of five companies each. Willich had a fondness for columnar formations and used skirmishers as a front-line fighting force. While most green volunteer regiments struggled to learn even basic formations, Willich’s troops easily mastered complex wheeling maneuvers, changed front effortlessly, and soon found themselves spending time on actual battle simulations, rather than parade ground showmanship. As their reputation grew in Camp Dennison, rival regiments became jealous. Colonel William Haines Lytle, a decorated Mexican war veteran, lead the Tenth Ohio Infantry, which included a large contingent of Irish immigrants and had a reputation as a hard-drinking bunch. They vowed to come down to the Ninth’s camp and “clean them out” one evening. Willich placed his men on alert and had them sleep on their arms. When rowdies from the Tenth showed up, the Ninth sprang to their feet, formed in line of battle, and stared down the troublemakers, who ran off.[5]

The presence of so many freethinking Turners among the officers and 48ers like Willich who had been defeated revolutionaries in the German states influenced many of the Ninth’s recruits and helped account for their early and enthusiastic response to Lincoln’s call. Certainly, most of the Ninth’s rank and file were likely motivated by a desire to protect their new homeland, earn an enlistment bounty, and prove to nativists that they, too, deserved to be treated as full citizens. A positive signal came in the form of a gift to the regiment from the independent National Guards, a militia composed largely of native-born citizens. Willich reminded the soldiers of the “painful recollections of the prejudices, which only a short time ago, goaded the citizens of this Republic to deadly hate against each other.” [6]

For leaders like Willich, however, much larger issues were at stake. Willich welcomed the Civil War as a crusade, not to preserve the federal Union, but to ensure the future of republican government “and the real freedom of the human race.” Willich’s battle in 1848 to destroy monarchial rule in Europe was for “the same rights of men against a combined conspiracy of a traitorous slave aristocracy with the same powers of the old world.” With the triumph of free labor over slavery, Willich dreamed that a socialist republic would emerge where workers would control the means of production. U.S. military leaders were willing to tolerate radicals like Willich, Franz Sigel, and others as they were highly influential community leaders who could drive recruitment and were themselves fully invested in the war effort.[7]

By the end of May, the Lincoln administration realized that the war would likely drag on for years and asked ninety-day recruits to reenlist for three years. Willich formed the regiment into a hollow square and pleaded to his troops. “As you have left home to fight the Rebels, so you should not return until you have matched word with deed. Stand by the Star-Spangled banner until it is out of danger.” All but a few reenlisted, earning the Ninth the distinction of being the first Ohio regiment to reenlist. Ohio’s first German regiment saw their first action in July, 1861, playing a key role in the small but important Union victory at Rich Mountain in western Virginia. They went on the fight with distinction in many battles, most notably at Mill Springs and at Chickamauga.[8]

If you are interested in learning more about the Ninth Ohio, I encourage you to read and follow Andrew Houghtaling’s excellent Facebook page, The Ninth Ohio, A Living History at https://www.facebook.com/NinthOhio.

David T. Dixon is the author of Radical Warrior: August Willich’s Journey from German Revolutionary to Union General (Univ. of Tennessee Press, 2020).

Notes:

[1] Constantin Grebner, We Were the Ninth: A History of the Ninth Regiment, Ohio Volunteer Infantry, April 17, 1861 to June 7, 1864 (Kent, Ohio: Kent State Univ. Press, 1987), 3–13. Gustav Tafel, The Cincinnati Germans in the Civil War, ed. Don Heinrich Tolzmann (Milford, Ohio: Little Miami Publishing, 2010), 27–28.

[2] R. Gerald McMurtry ed., “Lincoln Visited By A German Delegation of Workingmen In Cincinnati, Ohio, February 12, 1861” Lincoln Lore No. 1575 (May 1969), 1 ? 3.

[3] James Barnett, “August Willich, Soldier Extraordinary,” Bulletin of the Historical and Philosophical Society of Ohio, Vol. 20, No. 1 (January 1962), 62.

[4] Grebner, We Were the Ninth, 53.

[5] Frederick Finnup, The Story of My Life (Garden City, Kansas: Finnup Foundation, 1996), 24. Jacob D. Cox, “War Preparations in the North,” in Robert U. Johnson and Clarence C. Buell, eds., Battles and Leaders of the Civil War 4 Vols. (New York: The Century Co., 1887), 1: 98.

[6] Cincinnati Daily Commercial, 21 May 1861.

[7] Evansville Journal 2 August 1866.

[8] Grebner, We Were the Ninth, 52 ? 3.

David, what sort of enlistment bonuses were available to the early recruits in the 9th?

-Pat Young

Not meaning to speak for Mr. Dixon… but having ancestors who served in the First Iowa, it is my understanding that Lincoln’s initial call for volunteers in April 1861 was in accordance with the Militia Act of 1792 (amended 1795) which allowed the President to call out militias from the States in times of emergency for 90 days. No incentives were necessary because early Volunteer regiments were over-subscribed. “Expiring enlistments” came to attention of senior officials in late May; and notice was given to “re-enlist the 90-day regiments before their terms of service expired.” There was a frenzy in Cairo Illinois involving Brigadier General Prentiss and Colonel WHL Wallace to convert 90-day regiments into 3-year regiments. The incentive: if not more than 20 percent of the regiment declined to re-enlist, the affected regiment could keep its original numerical designation, its colors (and officers their seniority). Thus, there would be incentive of the majority of regiment members to “persuade” those on the fence to re-enlist. In addition, there does not appear to be financial “bonus” to re-enlist in 1861… However, promises of promotion were sometimes used. And it was common knowledge that the Republican Platform of 1860 included “initiation of a Homestead Act.” It is believed that a Rumour circulated, indicating that “Veterans with minimum one year of service would be entitled to 160 acres of homesteaded land.” The Homestead Act of 1862 was signed into law in May of that year; Union Veterans were permitted to deduct time served in military regiments from the occupancy term requirement.

[As a side note: the First Iowa was not re-enlisted in time, and was disbanded. Veterans of the Battle of Wilson’s Creek “enlisted” as corporals, sergeants and lieutenants in new regiments from the Hawkeye State, such as the 12th Iowa Volunteer Infantry…]

Thanks Mike. That was my understanding as well. But David wrote: “most of the Ninth’s rank and file were likely motivated by a desire to protect their new homeland, earn an enlistment bounty, and prove to nativists that they, too, deserved to be treated as full citizens.” So I was wondering if perhaps Ohio implemented bounties or bonuses at the start of the war.

Thanks for your comments Pat and Mike. In Grebner’s We Were the Ninth, pg 52, he mentions that a proclamation for Ohio Governor William Dennison had arrived promising $100 bonuses to 90 day Ohio volunteers who reenlisted for three years. Several respected scholars, including William Marvel, mention these bounties for reenlistment. On July 22, 1861 the US Congress did pass an act formally authorizing the $100 bounty (see OR, 3rd Series, I pg 382). Governor Dennison was instrumental in proposing the act and, if we believe Grebner, had already promised as much by late May.

David, thanks for including the OR (Series 3) Vol.1 reference in your response. Upon review of that volume I stumbled upon pages 368 – 372: a communication from the War Department to the Governor of New York dated 31 July 1861. After Bull Run. It contained reference to “the $100 bonus” and also directed attention to War Department General Orders No.15 (dated 4 May 1861 at Washington, signed by Adjutant General Lorenzo Thomas.) In the “Memorandum” attached to the orders, page 34, are details concerning the conditions under which the $100 Bonus would be paid.

Returning to OR (Series 3) Vol.1 page 382, the U.S. Congress authorization to pay the $100 Bonus is dated 22 July 1861… meaning the War Department General Orders No.15 were retroactive (and arbitrarily given the date of 4 May 1861.) Therefore, it can be surmised that “no legal authority” existed in May or June 1861 to pay a $100 Bonus to 3-month’s men who re-enlisted during that period: merely rumour and speculation (as it was not until Congress signed “An Act to Authorize the Employment of Volunteers to Aid in Enforcing the Laws and Protecting Public Property,” into Law July 1861, that such a bonus could be paid.)

Thanks for helping resolve how the “introduction of the $100 Bonus” came about.

Mike Maxwell

Great article. Were many of the German recruits “48ers” as well?

Thanks for your comment, Katy. There were many Forty-Eighters (German immigrants who emigrated to America in the years following the 1848 and 1849 revolutions in the German states) in the Federal Army. Most of these volunteers came to America for economic reasons, but a few thousand, including Franz Sigel, Friedrich Hecker, and August Willich, to name a few, were political refugees. These veterans of 1848 were folk heroes to many German immigrants and were extremely influential in recruiting German Americans to fight for the US Army.