Recruiting The Regiment: Politics by other means – the 36th Illinois Infantry Regiment goes to war

The 36th Illinois is really the closest thing I have to a hometown regiment. Company H of the 36th was recruited in Algonquin Township of McHenry County, Illinois, where I now live, and I find the graves of their veterans everywhere. Since I have lived here nearly forty years, I now regard them as my neighbors of long standing. In 1861 the township was rural, with a smattering of settlements; now, of course, it is mostly subdivision. The nearest large town was Elgin, downstream along the Fox River.

The men of the Fox River valley towns of Aurora and Elgin were, like many hundreds of thousands of their fellow citizens in the summer of 1861, afire with patriotic fervor. While no match in population for their big neighbor to the east, Chicago, which had an 1860 population of 109,000; the river communities strung along the Fox aggregated roughly 30,000 people. And in 1861, they were intent of raising a regiment in response to President Lincoln’s call for troops.

The result was the 36th Illinois Infantry, nicknamed the Fox River Regiment: a hybrid organization which included two companies of cavalry in addition to the ten normally authorized of infantry. When the men raised their hands to take the oath they numbered 1151 officers and men – 965 minus the two cavalry companies, who would not serve with the regiment for very long.

In 1860, despite the disparities in population, both Elgin and Aurora harbored hopes of rivaling Chicago. Both were rail and river towns, prosperous and growing, with amenities few other communities in the state could match. Aurora billed itself as “the city of lights,” not because townsfolk believed their city rivaled Paris, but because they were the first locality in Illinois to add gas streetlights. Widely-read newspapers—The Aurora Beacon and the Elgin Gazette—kept the valley up to date.

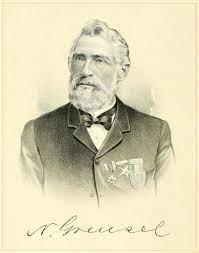

Though the men who formed the Fox River Regiment came from seven different Illinois counties, the heart of the regiment was always in those companies raised in Kane County along the Fox, especially Elgin and Aurora. The regiment’s first Colonel was Nicholas Greusel, from Aurora, as were the two men who followed him in that rank over the years, Silas Miller and Benjamin F. Campbell. The first Lieutenant Colonel was Edward S. Joslyn, a prominent and successful Elgin Lawyer. Alonzo H. Berry, also from Elgin, was the major. The regimental quartermaster was an Elgin resident; the surgeon, from Aurora. Four of the command’s twelve companies were raised in either Elgin or Aurora.

The men of the 36th first went into Camp Hammond in August, on the west bank of the Fox River just south of Aurora. There they spent an enjoyable month. At first, the accoutrements of soldiering were few: Tents were scarce and most men still wore their civilian attire. What was soon to be Company A, from Elgin, impressed everyone by arriving in some semblance of military order, having had the benefit of at least one officer (Edward Joslyn, who first enlisted with the 7th Illinois three months’ regiment in April) who had learned drill, and because they arrived bearing arms—“old fashioned and rusty muskets,” admitted the regimental history, “a sort of a cross between a cannon and liberty pole, that had been plundered from the armory of some half disbanded or wholly defunct militia company.”

With so many families so close, weekly company and regimental picnics were common. They drilled daily, but not onerously. There was plenty of time left for sport. Both boxing and “base ball filled up the intervals between mealtimes and drill.” Music was frequent, including a glee club as well as a regimental band.

Fortunately for the regiment’s future performance, Greusel proved to be an excellent choice for the colonelcy. Born in Bavaria, he and his family emigrated to the United States when he was seventeen, and he had made his way in the new world ever since. His first martial experience came in the Mexican-American War, where he commanded a company of Michigan Volunteers. In 1861, he was working for the Chicago, Burlington, & Quincy Railroad, and quickly returned to the colors. Greusel had also served in the 7th Illinois, leading a company, but was quickly elected major of that unit. In July, upon the expiration of the 7th’s three month term of service, he accepted the appointment to command the 36th. He proved to be a firm but fair disciplinarian, maintaining military order in what might otherwise have been an extended county fair; a quality the 36-ers would only grow to fully appreciate later.

Things became a bit more serious on September 23rd, they day they were mustered into Federal service. Passions ran high that day. Some few men developed reservations, refusing to commit; they were promptly ridiculed and expelled, sometimes violently. As recounted in the history, “among these were two Germans from Company E., whose courage oozing out at this supreme moment, . . . refused to take the prescribed oath. They were followed a half mile from camp by half a hundred madly excited men and remorselessly kicked and hustled about. . . [A]s a parting token . . . a horse whip was unmercifully administered to their backs. Their piteous cries for mercy awakened but little sympathy from their late and now infuriated comrades.”

The regiment’s real service began the next day. At 4:00 p.m., the entire regiment formed and marched to Aurora’s train depot, their path thronged with citizens intent on seeing them off. They were headed for Missouri. The cars hauled them first to Quincy, Illinois, where the regiment transferred to the steamboat Warsaw. There they also met their first veterans, the “brawny Irishmen” of the 23rd Illinois—Col. James A. Mulligan’s self-styled Irish Brigade—who had been captured and paroled at Lexington Missouri only a few days before. The men of the 36th peppered Mulligan’s boyos with questions about combat in general, the specifics of the Lexington fight, and the rebels. “Each had his story of adventure, of hardship and suffering to tell.”

On September 27th, debarking in St. Louis, the regiment was issued their first real arms and accoutrements. Companies A and B—the flank companies, upon whom most skirmishing duties would devolve—drew English-made Enfield rifled muskets. Much to their dismay, the men of the remaining infantry companies were issued .69 caliber Springfield smoothbores, converted to percussion. All of these factors: setting foot in the hostile territory of Missouri, the meeting with Mulligan’s men, and drawing weapons, worked on the men’s mood. The war seemed suddenly very real indeed.

The 36th was sent to Rolla, Missouri, in southwest Missouri. Rolla was the terminus of the Federal retreat after the battle of Wilson’s Creek, and troops were being forwarded there from all over. Rolla would be their home for the next few months. While there they saw no combat, excepting a few small patrols hunting bushwackers, but they learned much.

One of the most fascinating aspects of the American Civil War is how these early units handled the transition to military life. By the time the war broke out, democracy was deeply imbued in the American psyche, and was not to be deterred by anything like military discipline. This ethos did not mean that volunteers were unwilling to follow orders. Far from it, for they understood the need for that discipline. They were, however, particular about who would be giving those orders. Every white male, South as well as North, understood that he was equal and jealously guarded his voting privilege—which, in this case, meant electing their officers. They fully intended to have a say in who led them, and often rated those officers harshly if they failed to perform.

In early 1862, army professionals, horrified at the number of outright inept officers so elected, would institute checks and balances in the form of certification and review boards. But in 1861, the mechanisms for testing an officer’s knowledge or skills barely existed. As a result, disagreements and power struggles broke out in many regiments, producing infighting that often resembled nothing so much as a small-town political election.

The 36th proved to be no exception. Upon the regiment’s first formation, Col. Greusel found several officers wanting. Having led men in war, Greusel understood that command could not simply be a popularity contest, and he managed to secure alternatives to replace a couple of men he found wanting, chief among them Lieutenant Walker of company I. When the regimental surgeon found Walker medically unfit for service just before taking Federal service, Greusel immediately replaced him with Orville Merrill, an enlisted man home on leave from the 13th Illinois. Walker, aggrieved, did not give up the fight.

Walker showed up at Rolla that December, commission in hand, newly signed by Governor Richard Yates, re-appointing him to Company I. Gruesel refused to honor Walker’s appointment, though he had no legal grounds to do so. Walker refused to back down, and for several days Walker and Lieutenant Merrill stood side-by-side in company formations, “neither yielding an inch.” The controversy soon became the centerpiece of camp life, and, in uniquely American fashion, electioneering broke out.

Officers and men began to take sides, splitting mainly along the Elgin/Aurora rivalry divide. Over the course of several evenings, some of the officers gave stump speeches, with the regimental band obligingly migrating from speaker to speaker. As things became heated, accusations were bandied about, some of them leveled at Quartermaster Buck, whom some suspected of pocketing some of the ration monies. “The whole camp was in a ferment,” noted the regimental history.

Matters came to a head when Walker preferred charges against Greusel and the commander of Company I, Samuel C. Camp. Finally, a court martial board met in early January, and speedily resolved the issue when the mustering officer, Col. Brackett, testified that Walker never took the Federal oath on September 23. Walker soon departed, but tensions lingered. In a separate process, Quartermaster Buck resigned in March.

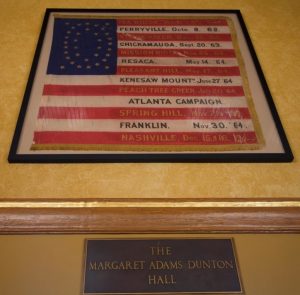

Despite what might seem an inauspicious start, the 36th Illinois went on to become one of the hardest fighting regiments of the entire war. Their first combat came at Pea Ridge. Transferred back east of the Mississippi, they fought in every battle of the Army of the Cumberland from Perryville through Nashville. At Stones River, they suffered a staggering 212 casualties. They were part of Federal Brigadier William Lytle’s brigade at Chickamauga, witnessing that officer’s fall. They belonged to Emerson Opdyke’s brigade at Franklin, helping to close the breach in the Union line. But they never stopped being unruly, democracy-minded Americans.

In SPI’s “Pea Ridge” it’s rated as an “R8” with a morale of 4. In SDI’s “Dead of Winter” it’s rated as an “R8” (though at half the scale) with a morale of 5. In GMT’s “River of Death” it’s also rated as an “R8” with a cohesion of 7. And in TG’s “This Terrible Sound” … well, you already know.

I have read that the Fox River valley had more volunteers per capita then any other place.Its interesting that these new recruits a short time latter would be transferred to the then Army of Ohio as seasoned veterans.My twice great grandfather John F Elliott received his commission to 1st Lt. for Meritorious conduct at Pea Ridge though her actually received in Nov.of 1862 at Nashville in the newly formed Army of the Cumberland.While on picket Dec 31,1862 he was wounded and captured at Stones River.He was swallowed by the Confederate tide crushed the Right wing.The rest of the Regiment fought on till they ran out of ammunition .Being they had the converted Springfields and their train had been flanked and captured by Confederates they were unable to secure .69 cal ammunition whereas they mounted bayonets and withdrew in good order.Their problem while not their own became a catalyst for standardizing to the more modern .577 which were issued ahead of the Tullahoma Campaign.