Recruiting The Regiment: The 154th New York—A Regiment That Wasn’t Meant To Be

ECW welcomes Mark H. Dunkelman

I’ve spent the past sixty years tracing a Civil War regiment that wasn’t in the plans. Had certain circumstances not occurred, the 154th New York Volunteer Infantry would not have been raised—and the lives of its 1,065 members (not to mention my life a century-plus later) would have been drastically different. What happened to bring the regiment into being?

After President Abraham Lincoln issued his call for 300,000 three-year volunteers on July 1, 1862, the federal War Department set New York State’s quota at 28 regiments. The state in turn ordered most of its 32 senatorial districts to form regimental districts, with a regimental camp in each district. One such was the state’s 32nd senatorial district, composed of Chautauqua and Cattaraugus counties.

How the two counties responded was typical. On July 12 a convention of delegates from both gathered in Mayville, the Chautauqua County seat, and resolved to raise the single regiment apportioned to their district, six companies to be recruited in Chautauqua and the remaining four in Cattaraugus County. Five days later a similar meeting was held in Ellicottville, the Cattaraugus County seat. Committees of recruiting supervisors were chosen for each town in both counties. Governor Edwin D. Morgan announced a $50 state bounty would now supplement the $100 federal bounty for each volunteer. In the following days, towns throughout Chautauqua and Cattaraugus also promised bounties to recruits.

At a meeting in Dunkirk on July 19, a committee of prominent men from both counties, appointed by Governor Morgan and the state adjutant general, formally petitioned Morgan to grant recruiting authorizations to 20 individuals. The committee chairman, Augustus F. Allen of Jamestown, was designated colonel and commandant of the district military camp, to be located on the fairgrounds in his home town.

The atmosphere surrounding recruiting in the summer of 1862 differed from that of the spring of 1861. When the Fort Sumter battle ignited the war in the spring of 1861, there was a heady rush to the colors. Since then, the war had tightened its grip on the country, the battles had grown deadlier, and most recently McClellan’s long-awaited campaign on the Virginia Peninsula had sputtered to an inglorious end, leaving the fate of the Union cause uncertain at best. The 1861 volunteers had signed up for a war they could only imagine. A year of actual warfare had changed perceptions. The 1862 recruits sensed what kind of war they had volunteered for.

Town by town, war meetings were held in village churches, schoolhouses, and meeting halls. Speeches were made, songs were sung, bounties were donated, volunteers were cheered. By mid-August, the district’s allotted ten companies were reported to be full. Colonel Allen’s committee met in Jamestown on August 14 and proposed a set of veteran officers for the new regiment. Two committeemen were dispatched to Albany to confer with Governor Morgan.

So matters might have remained, with the 32nd District’s regiment raised and the recruiting drive completed, had Governor Morgan not welcomed to Albany another visitor from the district. During his visit, Addison G. Rice changed the dynamics of the district recruiting drive.

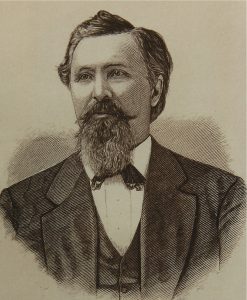

Rice, an Ellicottville lawyer and state assemblyman, had been active in the drive since its inception. After meeting with Morgan, Rice sent a telegram to Ellicottville on August 19: “Cattaraugus has a whole Regiment of Volunteers—10 Companies.” The governor had appointed Rice provisional colonel, with authority to recruit the proposed regiment.

Two days later Augustus Allen’s committee approved the plan to raise a second regiment in the district. By then six companies of Chautauqua County volunteers had signed up; there were four from Cattaraugus—the exact ratio of the formally proposed original regiment. That left six companies to be raised in Cattaraugus and four in Chautauqua to complete the impromptu second regiment. The committee set Chautauqua’s quota at 1,806 men, and Cattaraugus’s at 1,358.

Recruiting continued through the rest of August and into September. When it ended, Chautauqua had its full regiment of ten companies, the 112th New York Volunteer Infantry. Two surplus Chautauqua companies joined eight Cattaraugus companies to form the second, initially unplanned, regiment, which was designated the 154th New York. Both units left Jamestown in September for the front; both had active, far-ranging careers. The 112th served in the 7th, 10th, 18th, and 24th Corps and fought at Cold Harbor and the siege of Petersburg in Virginia, and Fort Fisher in North Carolina. The 154th served in the 11th and 20th Corps at Chancellorsville, Gettysburg, Chattanooga, the Atlanta campaign, and Sherman’s marches through Georgia and the Carolinas.

Rice can rightly be called a classic political colonel of the type that unfortunately flourished to sizable extent in the war’s early years. It often took time to weed out incompetent officers, but Rice, whose only military experience was in the prewar militia, weeded himself. He accepted the provisional colonelcy with the understanding that after organizing the regiment, he would relinquish command to an experienced officer. That officer was Rice’s former law student and partner Patrick Henry Jones. This on the face of it sounds like an overtly political deal, but Jones was well qualified to be colonel—he was an 1861 volunteer and veteran officer who had been promoted from first lieutenant to adjutant to major of the 37th New York. He and Rice were political rivals: Jones a Democrat, Rice a Republican. Jones would command Rice’s regiment for much of its service (and turn Republican in the process), and eventually be promoted to brigadier general. After the war ended, the two would reconnect as partners in a New York City law firm.

Addison Rice can truly be called the father of the 154th New York, but he considered the raising of the regiment to be eclipsed by its subsequent costly service in close to three years of war. When regimental historian E. D. Northrup asked him to contribute an autobiographical sketch to a history of the 154th, Rice replied with befitting modesty:

I thank you for inviting me to take a place in the work, but I am compelled to say that I do not think that any such notice of me would be just to the soldiers who composed that Regiment. I was not an officer of the Regiment; was never commissioned or mustered in, and had no authority in the premises, except to organize & command it during its organization, on authority which came from the Governor of the state. I simply performed that duty & handed the Regiment over to its officers in Va. I am not entitled to any of the military credit—the credit due & always to be given to the soldiers . . . You will understand my motives. I should be proud of a place with the soldiers, but I am not entitled to it & it would not be just to them to place me in their honored line.

With his bold and unexpected late call for a second regiment to be raised in the 32nd District, by superintending its organization, and by leading the command to the front in Virginia, Addison Rice added another thousand men to Mr. Lincoln’s army. By bringing an entire regiment into being, he deserved the accolades he was reluctant to accept.

Enjoyed your book on Sherman’s March!