From the Chickahominy to the James: June 4-14, 1864

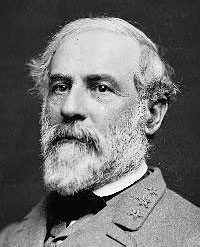

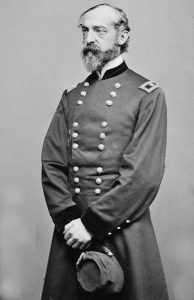

In the aftermath of Cold Harbor, the armies led by Robert E. Lee and George Meade were at a strategic stalemate less than twenty miles from Richmond. The advantage though was to the Confederates. Lee still held Richmond and his army was in overall better shape. Despite some heavy officer losses, Lee’s men had high morale and with some exceptions his brigades were battered but still cohesive fighting units.

The Army of the Potomac, while not destroyed, had suffered a reverse that was even worse than the infamous charges at Fredericksburg. Their morale had plummeted. John West Haley of the 17th Maine wrote “we were tired of charging earthworks. Many soldiers expressed freely their scorn of Grant’s alleged generalship, which consists of launching men against breastworks. It is well known that one man behind works is as good as three outside the works.”[1] Surgeon Daniel M. Holt of the 121st New York wrote, “If losing sixty thousand men is a slight loss, I never want to see a heavy one. We, as a regiment, have almost ceased to exist, and if the next six months prove as disastrous to us as the last six weeks have, not a soul will be left to recite the wholesale slaughter which has taken place on the sacred soil of Virginia.”[2] Charles S. Wainwright, chief of artillery for V Corps, sharply criticized the frontal attacks as “a mere shoving forward of a brigade or two now here now there, like a chess-player shoving out his pieces and then drawing them right back.”[3] Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain, who was a little less critical, thought Grant “was like Thor, the hammer, striking blow after blow, intent on his purpose to beat his way through, somewhat reckless of the cost.”[4]

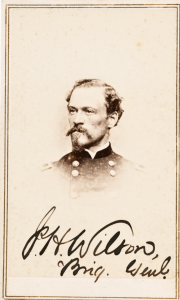

Just as bad, a fresh round of bickering took place, mostly between Meade and William F. Smith, commander of XVIII Corps. James Wilson, one of the army’s cavalry commanders, and John Rawlins, Grant’s chief of staff, blamed the poor tactics on Cyrus Comstock. Although a capable engineer, Comstock had encouraged aggressive assault tactics throughout the 1864 campaign. After Cold Harbor Rawlins worked to limit Comstock’s influence on Grant.

In the aftermath of Cold Harbor Grant was offered several plans. Comstock proposed taking the army on a large swing to destroy Lee’s railroad network. Meade preferred to pin Lee at Cold Harbor and let Phillip Sheridan’s cavalry raid the rear. Henry Halleck suggested that Grant position himself north of Richmond in order to protect the approaches to Washington and invest Richmond through an attritional campaign. Not wishing to settle for siege, Grant wanted to take Petersburg. The city was a key Southern railroad hub and manufacturing center. Its fall would mean the fall of Richmond and in turn the reelection of Abraham Lincoln, who for his part was in a tough political situation. The thirteen amendment, which would abolish slavery, was now in danger of being scuttled, while Lincoln angered the Radicals by rejecting of the Wade-Davis Bill, which would enact a relatively stern Reconstruction plan on the defeated South. On May 31 some Radical Republicans met in Cleveland, Ohio and nominated John C. Fremont for president. Benjamin Butler, himself a War Democrat turned Radical, declared “This country has more vitality than any other on earth if it can stand this sort of administration for another four years.”[5]

Lincoln needed a victory and in early June he could hardly look elsewhere. In the west, the Confederates had scored victories at New Hope Church, Pickett’s Mill, and Brice Crossroads. A minor and much publicized victory at Dallas gave Lincoln’s allies some hope, but for now the Union war effort had stalled.

To take Petersburg, Grant would swing Meade’s army across the James River. It would take hard marching and fighting to seize Petersburg, but Grant seemed unsure if he could take Petersburg by storm. On June 6 he wrote, “This is likely to prove a very tedious job I have on hand but I feel very confident of ultimate success.”[6] This uncertainty would have a detrimental effect upon the coming campaign as it unfolded.

Grant’s developing plans were influenced by good news from the Shenandoah Valley. On June 5 David Hunter smashed a Confederate force at Piedmont and was ravaging the area. The South was in an uproar, and Lee had to do something. Now confident that his lines would hold, Lee felt free to send forces into the Shenandoah Valley. He dispatched Jubal Early with 10,000 men to defeat Hunter and if possible threaten Washington D.C., a kind of retread of the strategy he employed in 1862. Early’s maneuver to the Shenandoah was threatened when Sheridan was sent on a massive raid. It culminated the battle of Trevilian Station on June 11. Although both sides claimed victory, Sheridan was prevented from joining Hunter and Early made his way to the Valley. The battle also deprived Lee and Grant of most of their cavalry, with major repercussions for the fighting ahead.

On June 7 Grant sent Horace Porter and Comstock to choose a site for the crossing of the James River and meet with Butler to discuss Grant’s river crossing, but not Grant’s plans for Petersburg. After the meeting with Porter and Comstock, Butler decided to seize Petersburg, not knowing that Grant intended the same thing. He sent a force under Quincy Gillmore, but the commander failed in his June 9 attack. All the battle did was cause P.G.T. Beauregard, the commander south of the James River, to send more men to Petersburg. However, Beauregard kept most of his men at Bermuda Hundred, facing the X Corps.

For the march on Petersburg, Grant had Smith’s XVIII Corps return to Bermuda Hundred. The rest of the army would shift to the James River, where a massive pontoon bridge would be built. Grant informed Butler that Petersburg was the goal but neither Smith nor Meade. Smith did not know until June 14 when he met with Butler, and the day was spent preparing to attack on June 15.

On June 12-13, the Army of the Potomac moved across the Chickahominy River, which ran along the south of Cold Harbor. The withdrawal was mostly successful. Lee’s men detected nothing. Yet there was one major delay. The Long Bridge across the Chickahominy was gone. The area was contested by Rebel cavalry and it took hours to defeat them and build a new bridge. During the fighting, Wilson ran afoul of Gouverneur Kemble Warren, the touchy commander of V Corps. Warren told one messenger “Tell general Wilson if he can’t lay that bridge to get out of the way with his damned cavalry and I’ll lay it!”[7] Wilson refused to shake Warren’s hand later that day and told Grant “send for Parker the Indian chief, and after giving him a tomahawk, a scalping knife and the worst whiskey the Commissary Department can supply, send him out with orders to bring the scalps of major generals.”[8] When Grant asked who should be scalped, Wilson described Warren’s behavior in detail.

On June 13 a fierce skirmish was fought at at Riddell’s Shop, a crossroads less than twenty miles from Richmond. Meanwhile, the vanguard of the army reached the James River at Wyanoke Neck although there were no transports ready to move them across. Meanwhile, nearly 500 engineers under James Duane, assisted by Godfrey Weitzel of Butler’s staff, started the work and by June 14 they finished an impressive bridge, nearly 2,100 feet long, and consisting of 101 pontoon boats.

On June 14 Grant met with Butler and told him to pressure Bermuda Hundred. Smith would move south of the Appomattox River and attack Petersburg. II Corps would be ferried over and march to Petersburg to support Smith.

The Confederate reaction to Grant’s maneuvering was muddled. Before Grant withdrew, Lee actually feared Grant was about to strike again. Martin Gary, commanding cavalry at Riddell’s Shop, thought the main Union thrust was in his sector. With Early gone, Lee’s options were limited and one error could expose Richmond. With most of his cavalry elsewhere, Lee’s horsemen could not penetrate Wilson’s screen. Lee decided Grant was moving on Chaffin’s Bluff and shifted his men to guard it, covering Riddell’s Shop, Malvern Hill, and the New Market Road. Although troop transports were reportedly seen going to Bermuda Hundred, it was confirmed that on XVIII Corps was onboard. In reaction, Lee sent Robert Hoke’s division to Beauregard, an outfit Beauregard had loaned him weeks before.

On the evening of June 14, Grant and Meade were in a good position to take Petersburg. Lee had failed to detect their position and he was fixated on the spot Grant had no intention of attacking. Beauregard, while aware of the danger to Petersburg, was at Bermuda Hundred. Yet, the Army of the Potomac had a history of defeats that had begun so beautifully. Before the battles of Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, and the Wilderness, the army had out-maneuvered Lee only to meet defeat in battle. Would this time be different?

————

[1] John West Haley, Rebel Yell and Yankee Hurrah: The Civil War Journal of a Maine Volunteer (Camden: Down East Books, 1985), 165.

[2] Daniel Holt, A Surgeon’s Civil War (Ohio: Kent State University Press, 2000), 205.

[3] Charles Wainwright, A Diary of Battle (New York: Harcourt, Brace and the World, 1962), 381.

[4] Ernest B. Furgurson, Not War but Murder: Cold Harbor 1864 (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2000), 254

[5] Benjamin F. Butler, Private and Official Correspondence of Gen. Benjamin F. Butler Vol. IV (Norwood, MA: The Plimpton Press, 1917), 337.

[6] Grant, The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant, Vol. XI, (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1967), 25.

[7] James H. Wilson, 399.

[8] Ibid., 401.

No. Grant/Meade blew the perfect opportunity to end it. Without their munitions base and the Petersburg/Richmond railroad nexus the Confederates were doomed. Readers might remember that Hooker actually had wanted to jump ugly at Richmond when Lee began his Great Raid in 1863, but Lincoln and the empty brass suits vetoed him. Lincoln was obsessed with “going after Lee’s army”. Well, without munitions, Lee would have been forced into a hasty retreat. Hooker guessed this. Honest Abe never did.

My ancestor was in Co. D US Engineers. According to his diary, after they had constructed the pontoon bridge, they had to return and repair it that night because it was struck by a “steamer”. Duane, by the way, wrote the War Department’s official Engineers Manual.