Braxton Bragg’s Beach Vacation – Pensacola in the Early Months of the Civil War

Even the most casual of Civil War buffs knows that the war began in Charleston, South Carolina – when Confederate batteries opened fire on the Union-occupied Fort Sumter and its 85 defenders. Many may also know that war had an equally likely chance of beginning in the Gulf of Mexico, at Fort Pickens in Pensacola, Florida where Braxton Bragg, rather than P. G. T. Beauregard, might have made a name for himself as the first military hero of the fledging Confederate nation. As it happened, however, Sumter fell to the Confederacy and Pickens remained a Union bastion throughout the war, preventing the harbor town of Pensacola from ever falling into Confederate hands. A sampling of Braxton Bragg’s correspondence while in command in Pensacola, however, reveals several interesting themes that would come to define the Confederate war effort—and which are worth briefly surveying.

Pensacola probably seemed an unlikely place for a Civil War career to begin—especially for the man who would become the fifth-highest ranking officer in the Confederacy. Despite its peripheral status in modern treatments of the war, however, the city and its harbor defenses caused much consternation for the Confederate government in the early months of 1861. Both Fort Pickens and its neighbor, Fort Barrancas, were sterling examples of the brick harbor installations favored by the antebellum regular army—and held valuable supplies in the form of weapons and ammunition. Supplies that would be essential, in fact, to creating an army in a nation that had only just begun its existence. In order to seize the war materiel in Pensacola Harbor, and move it to the interior of the Confederacy, the Confederate Congress passed a resolution on February 15, 1861 urging Jefferson Davis to take immediate steps to gain possession of Fort Pickens.

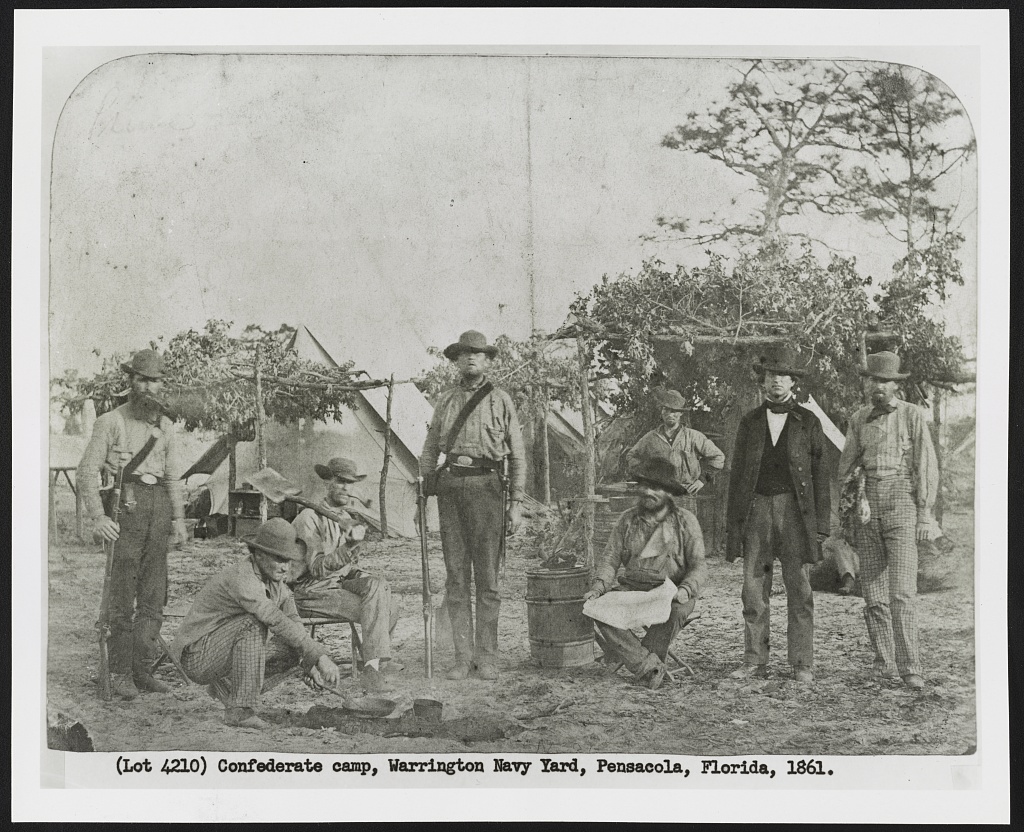

On March 7, Davis assigned Braxton Bragg to command the region around Pensacola and to manage the new recruits for the Confederate army present in the city. Bragg found the city in “a most deplorable condition.” He told his wife that men under his command were raw but passionate—each certain that they could individually invade Fort Pickens and take on the garrison and any Union naval support nearby. Bragg told Elise he would build the men into an army with discipline. Photographs of the men at Pensacola revealed the accuracy of Bragg’s description of the soldiers. There were no standard uniforms for Confederate troops until 1863 and the varied dress of the men at Pensacola underscored this fact. Bragg’s acerbic comments about troop self-belief, while on brand for the perpetually perturbed general, also highlighted the tensions between West Point trained officers and citizen-soldiers as the reality of training and drill replaced the initial thrill of enlisting and the desire to go to war.

Bragg also told Elise he was flattered by the trust Davis had placed in him—saying the Confederate president expected a great deal from the defenders of Pensacola and Charleston. He called Davis an old friend—indicating the loyalty the Mississippian felt toward him; a loyalty that later proved detrimental to the progress of Confederate arms. But Bragg was right. His appointment to command in Pensacola—given the harbor’s importance—did reflect Davis’s confidence in the 1837 West Point graduate, with whom he had fought with on the Mexican War battlefield of Buena Vista. [I have written more about Davis and Bragg’s shared loyalty and its effect on the Confederate war effort–in an essay out in an ECW collection this coming fall.]

While Bragg felt confident of his position within the new Confederate army, the citizens of Pensacola did not share this state of security with their assigned defender. Concerned local residents wrote to Bragg fretting over Union plots to destroy Pensacola Harbor. One “Southern Woman” spotted a public notice in a local Pensacola newspaper and forwarded it to the commanding general on April 24—suggesting that he do something to prevent the secret attack she had convinced herself was imminent. She assured Bragg that, despite basing her claims on a newspaper article, she had “spoken of this to no one.” The anonymous woman feared Union occupation before the war had really begun in earnest and her self-identification revealed the ways in which national identity was already shifting in the wake of Southern secession, and particularly among Southern women. Bragg’s wife likewise wrote in June of her disappointment that Union troops sick with scurvy inside Fort Pickens had been evacuated—telling her husband she supposed “there is no killing them off that way.”

Bragg’s command at Pensacola eventually expanded to include much of Western Florida’s coast, as well as the city of Mobile, Alabama. Bragg fretted that the harbor there would be indefensible against a massed Union attack, but he was called away before he could implement any strategic strengthening of Confederate defenses in the Yellowhammer state. That work fell to other officers, as Bragg was ordered to join Albert Sidney Johnston at Corinth, Mississippi with 10,000 of his Gulf Coast troops in the wake of the Union’s capture of forts Henry and Donelson in February, 1862. Bragg would not return to the Gulf Coast for the remainder of the war. And the early worries about Pensacola faded from a position of importance as Lincoln and Davis watched their troops clash in Virginia and Tennessee. In one of the twists of fate that so often appears in the study of history, however, Bragg did eventually return to the Gulf Coast. Though he died in Galveston, Texas and lived most of his non-military life in North Carolina and Louisiana, Bragg was buried some 60 miles away from his first Civil War command—in Magnolia Cemetery in Mobile.

Quotes taken from Don C. Seitz, Braxton Bragg, General of the Confederacy (Columbia, S. C.: The State Company, 1924)

Thank- you for initiating this discussion of Pensacola, and the role of combatants occupying opposite shores of “the deepest harbor on the Gulf Coast” in nearly sparking the Civil War. The first Rebel commander at Pensacola was West Point trained William H. Chase, acting on behalf of the State of Florida (which seceded 10 JAN 1861.) Unfortunately for Rebel Florida, Lieutenant Adam Slemmer, U.S. Army First Artillery, celebrated Florida’s secession by occupying the strongest position on Pensacola Bay – Fort Pickens – which because of its isolated position was easily supported by U.S. Navy warships and supply ships operating in the Gulf of Mexico. Chase, who had built all four of the forts, defending Pensacola Bay and its Navy Yard, demanded Slemmer surrender control of Fort Pickens; but Slemmer refused. And Militia General Chase was soon replaced by Confederate Brigadier General Braxton Bragg. Newspapers of the first months of 1861 gave equal billing to Fort Sumter and Fort Pickens as likely flashpoints for war; and thousands of men streamed to both locations, certain, “the war will start HERE.” Following the Inauguration of the Lincoln Administration on 4 March 1861, both potential flashpoints slid inexorably towards war. It was not so much a question of when, but WHERE? (There are claims that the Commander of the U.S. Navy flotilla hovering just south of Fort Pickens was ordered to land troops at Fort Pickens – which likely would have precipitated war – but the Naval officer refused… and war was initiated at Fort Sumter a few days later, instead.)

Thanks for this comment, Mike! I think there are some great stories to be told about exactly the era you’re talking about in Pensacola and the way in which rumor and speculation caused people to act. I plan to look into the US naval sources more in my free time!

Again, Thanks for refreshing interest in “sleepy” Pensacola. OR ser. 1 vol.1 contains details of the early 1861 struggle for control of Pensacola Bay. And The Naval Records of the Union and Confederate Navies (OR—Navy ser.1 vol.4) contains the early Pensacola-related naval records.

And Harper’s Weekly is a good source of sketches [below images sketched in vicinity of Pensacola Navy Yard – under Confederate control – found in Vol.5 1861 June 22 and available online via archive.org]

https://archive.org/details/harpersweeklyv5bonn/page/395/mode/1up

One of my first Civil War site visits as a kid was to Fort Barrancas during a Pensacola beach family vacation!

I have yet to visit, but as a Bragg-ophile I want to see it and Mobile soon!

… Two new things I’ve learned today. Florida was called the “Yellowhammer State” and that I’ve been driving right by Bragg’s grave without even knowing it! I feel very un-Floridian for not knowing these things. Thank you for the post, Cecily!

Actually Alabama is the Yellowhammer State, so you don’t have to feel bad at all!