Re-evaluating Ezra Carman, Pt. 2: Georgians in the East Woods

ECW welcomes back Chris Bryan

(Part 1 of Re-evaluating Ezra Carman can be read here.)

During Brig. Gen. John Bell Hood’s counterattack at Antietam, the 4th Alabama became increasingly detached from its brigade by fences while it advanced along the Smoketown Road. Captain William Robbins, suddenly thrust into command by casualties, later wrote, “…just as I got the regiment into line as above said there appeared a fragment of a Georgia Regt. About 5 small companies close by our right; how that fragment had got detached from its belongings and to what brigade etc. it did belong I did not then take time to inquire and I don’t know yet, nor am I sure of its own number now, for I forget but I think it was 21st or 29th Ga. (it was in the 20s somewhere) it had no field officer with it, but had its regimental flag, and its gallant boys called out loudly to me that they had got off from their proper command and asked what to do. I directed them to form at once on the right of the 4th Ala. and go ahead with us, which they did like lightning.”[1]

The 4th Alabama then entered the East Woods and faced the 10th Maine and later two brigades of Brig. Gen. George Sears Greene’s division of the Union Twelfth Corps. Robbins’s Alabamians fought alongside the 5th Texas and the wayward Georgians described above.

Who were these Georgians? This was a central question for the 10th Maine’s historian, John Mead Gould. Gould conducted correspondences with veterans of both armies during the 1870s through 1900s. His initial aims were to nail down which regiments fought the 10th Maine and to prove that Brig. Gen. Joseph K. F. Mansfield’s mortal wound occurred at the 10th Maine’s line. This effort expanded, supporting distinguished Antietam historian Ezra Carman, who sought to establish the facts of the entire battlefield. Gould limited himself to researching the First and Twelfth Corps and their opponents. My last ECW post questioned a conclusion drawn by Carman and later historians regarding the 2nd South Carolina. Here again, I explore Carman’s conclusion that the 21st Georgia of Brig. Gen. Isaac Trimble’s brigade fought alongside the 4th Alabama and 5th Texas in the East Woods.[2]

James Cooper Nisbet, in his history of the 21st Georgia, wrote that his regiment advanced into and through the East Woods, deploying in “open order.” Nisbet asserted that he fought the 10th Maine in this fashion until “The 10th Maine retired and our firing ceased.” He mentioned that it was then 11 a.m. Confusion over the time was understandable, though the 10th Maine withdrew closer to 8:20 a.m. as Brig. Gen. George Sears Greene’s division swept through the East Woods driving off the “Georgians” and two regiments from Brig. Gen. John Bell Hood’s division, the 4th Alabama and 5th Texas with heavy fighting. Nisbet did not mention joining Hood’s regiments or the two Federal brigades sweeping through the woods, neither in his history, nor in correspondences with Gould. Nisbet wrote to Carman in 1895, but that letter has not been found. A sketched map sent to Carman from John M. James of the 21st Georgia, dated February 21, 1895, notes that the 21st was reinforced by Hood’s Texas brigade and then advanced along the Smoketown road and into the East Woods, on the right of the road.[3]

Nisbet also maintained in his history that Gould, in his correspondence, had paid “high tribute to the gallantry of the 21st Ga. Regt. in this advanced position” [in the East Woods]. Nisbet and Gould corresponded in 1891. In an 1892 National Tribune article, Gould described his quest to determine who fought the 10th Maine in the East Woods. He chronologically described his efforts. When he reached his inquiry of Brig. Gen. Isaac Trimble’s brigade, which included the 21st Georgia, Gould wrote that he “found at the end that they had played their terrible part and melted away before the 10th Me. came into the woods.” Despite Nesbit’s claim to the contrary, it does not seem that Gould came to the conclusion that the 10th Maine fought the 21st Georgia and likely did not praise the 21st Georgia specifically.[4]

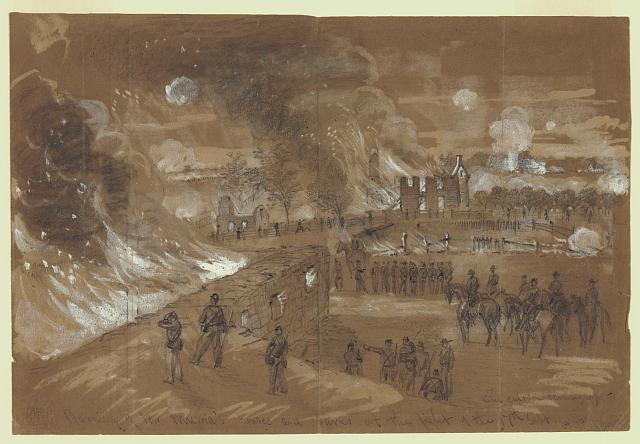

Gould had by then concluded that a skirmish battalion from Col. Alfred Holt Colquitt’s brigade was the Georgians in question. This battalion consisted of one company from each regiment (6th, 23rd, 27th, 28th Georgia, and 13th Alabama). These companies drilled regularly to deploy when required, each company covering its own regiment and falling back into line when the regiment came forward, requiring no orders other than from the company commanders. Captain George Grattan, Colquitt’s aide-de-camp, wrote that this method proved “effective and convenient.” The battalion sometimes operated independently, and it went forward on September 16, commanded by Capt. William M. Arnold. Near the East Woods, it skirmished alongside Hood’s skirmish line against a Pennsylvania Reserves brigade before retiring to the Roulette Farm. It returned forward early on September 17 and, from a field southeast of East Woods, engaged Federals within the woods. Arnold was soon wounded and the 23rd Georgia’s Capt. Marcus R. Ballenger took command. Ballenger moved the battalion southeast looking for the brigade. Discovering that it had moved on, the battalion headed northwest, reaching the Smoketown Road as the 4th Alabama neared the East Woods north of the blazing Mumma House, which Confederates had set on fire that morning. While the skirmish battalion, 4th Alabama, and 5th Texas fought in the woods, the rest of Colquitt’s brigade marched past the burning house and entered the D.R. Miller Cornfield just west of the East Woods. The brigade fought bravely in the face of calamity, and its story has been underrepresented to date.[5]

In 1891, the 4th Alabama’s Captain Robbins showed initial skepticism that these Georgians had been from Colquitt’s skirmish battalion, because he remembered seeing the men with colors. It is this point that Carman used in his manuscript to assert that these were not Colquitt’s men. Robbins’s position evolved, however, and he ultimately shared Gould’s view. In 1892, Robbins wrote to Gould, “About the flag…how it is that these Georgians (if they were the rifle battalion) say they had none_I can’t explain it. I think such a battalion would + should have a flag to guide them + to rally on as skirmishers. Probably or possibly it was improvised for the occasion somehow + Therefore is forgotten by them. I can’t remember now seeing the flag of the 4th Ala anywhere in that wood, + yet it was there with us.” This admission about his memory of his own regiment’s flag was clearly an earnest examination of his memory and tosses the basis of Carman’s conclusion into question. By 1896, Robbins questioned Carman, “was it not Colquitt’s Brigade which had out a kind of skirmish battalion made up of a company from each regiment and which operated in some sense as an independent battalion, carrying its own flag? I think this was so. Now such a battalion…came to me on the right of the 4th Ala…” R. T. Coles’s history of the 4th Alabama also specified both Colquitt’s skirmish battalion and Captain Arnold as the Georgians that joined his regiment.[6]

Colquitt’s men held a range of opinions on this subject. A few of Gould’s correspondents recollected that the skirmish battalion either had not been established yet or was not deployed that day. Indeed, Colquitt did not mention it in his official report or in his letters to Gould. George L. Cain of the 28th Georgia was the main polemical protagonist for this position. Besides asserting to Gould that the battalion was not yet established, he also threw into question the idea that Company A of each regiment was used. Cain instead suggested that the 28th’s Company K was used and that it was with the regiment that morning, asserting that he saw two of its members become casualties while crossing the Smoketown Road.[7]

In 1895, one week after Cain’s last correspondence, Judge George Grattan, Colquitt’s Aide-de-Camp at Antietam was “pretty sure that Sidney Lewis is correct in his statement that the Batalion [sic] had an engagement in the wood the next morning [September 17th] but I cannot say what company of the 28th Ga was with the Batalion, if any. My impression was that the right company of each regiment formed the skirmish Batalion at this time, and if so that would account for Co K. 28 Ga Regt not being with the Bat. Sidney Lewis was a member of Capt Arnold’s Co. (A) of the 6th Ga Regt. and a very intelligent and reliable man…my impression is that, Lewis is correct…about the skirmish Batalion having the Engagement in the wood.”[8]

The 6th Georgia’s Sidney Lewis provided Gould’s principal evidence for Colquitt’s battalion. Lewis produced detailed descriptions of the battalion’s movements on September 16 and 17 and named the 4th Alabama as the regiment with which the battalion fought in the woods. R.V. Cobb of the 27th Georgia also indicated, tangentially, that the skirmish battalion was deployed by recalling a conversation about the fighting in front in which he referred to the battalion. Thomas J. Marshall, 6th Georgia, also asserted that Arnold and the battalion fought in the East Woods.[9]

It is possible that Carman, and every secondary history to date, is correct that the 21st Georgia fought alongside the 4th Alabama and 5th Texas. John James’ map, mentioned above, appears to be the strongest evidence supporting the 21st Georgia. However, available evidence suggests more strongly that the 21st Georgia entered the woods and briefly fought remnants of Hooker’s First Corps and withdrew before or during Hood’s assault. It seems likely that the “Georgians” that fought with the 4th Alabama and 5th Texas were from Colquitt’s brigade and included a company from Alabama.

Chris Bryan’s first book, Cedar Mountain to Antietam: A Civil War Campaign History of the Union XII Corps, July – September 1862, will be published by Savas Beatie in November 2021. Bryan earned a Bachelor of Science degree in History from the United States Naval Academy, a Master of Arts in Liberal Arts from St. John’s College, and a Master in Historic Preservation from the University of Maryland.

[1] William Robbins to John Mead Gould, March 25, 1891, Antietam Papers, Dartmouth College (APD).

[2] Ezra Carman, Maryland Campaign of September 1862, Vol. 2: Antietam, ed. Thomas G. Clemens (El Dorado Hills, CA, 2012), 91.

[3] James Cooper Nisbet, Four Years on the Firing Line. (Chattanooga, 1914), 154-5; James C. Nisbet to Gould, April 21, 1891 and John M. James Map, February 21, 1895, APD.

[4] Nisbet, Four Years on the Firing Line, 154-5; National Tribune, August 25, 1892.

[5] Carman, Maryland Campaign 2:127; George Grattan to Gould, August 15, 1892, Sidney Lewis to Gould, May 7 and June 4, 1892, APD.

[6] Carman, Maryland Campaign 2:91; Robbins to Gould, June 14, 1892, APD; Robbins to Carman, October 9, 1896, National Archives-Antietam Studies, RG92:707 (NA-AS); Jeffrey Stocker, ed. From Huntsville to Appomattox: R. T. Cole’s History of the 4th Regiment, Alabama Volunteer Infantry, C.S.A., Army of Northern Virginia (Knoxville, 1996), 67-68.

[7] George Cain to Gould, March 4, 1893, June 27, 1895, and July 13, 1895, APD.

[8] George Grattan to Gould, July 20, 1895, APD.

[9] Sidney Lewis to Gould, May 7 and June 4, 1892, R.V. Cobb to Gould, February 23, 1892, T.J. Marshall to Gould, April 29, 1892, APD.

Interesting article on the tactical aspects.