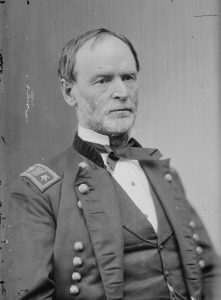

Book Review: The Scourge of War: The Life of William Tecumseh Sherman

The Scourge of War: The Life of William Tecumseh Sherman

By Brian Holden Reid

Oxford University Press, 2020

$34.95

Reviewed by Derek D. Maxfield

There is no shortage of biographies of William Tecumseh Sherman. Although Civil War studies are seemingly out of favor, works about the eccentric red head continue to flow from the presses. Most of these are mediocre. But the latest by military historian Brian Holden Reid is a refreshing change which makes important contributions to Sherman studies. It is also a great read.

Best known for his America’s Civil War: The Operational Battlefield, 1861-1863, Reid was recently awarded the prestigious Samuel Eliot Morison Prize from the Society for Military History. He is presently Professor of American History and Military Institutions at King’s College London, UK.

In his introduction, Reid reminds the reader of Sherman’s “black” reputation. “Sherman was a stern, insistent, and brutal man,” who “appeared happy to unleash on the South unprecedented devastation by fire and sword.” But, Reid argues, “there is only one difficulty with it: this diabolical image veers drastically from the reality of the historical Sherman.”

Historians have long wondered what happened to Sherman in Kentucky when he asked to be relieved of duty and showed signs of extreme anxiety. Surely, when measured against later events the high-strung red head was not insane, as the newspapers suggested. Depression and anxiety seem likely. Reid offers a fresh take on the controversy. Disclaiming Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), which “is a chronic, relapsing disorder” Reid concludes it would have prevented the general’s later great success. Instead, Reid suggests adjustment disorder.

Adjustment disorder is a condition that occurs when subjective distress and emotional disturbance interfere with social functioning and performance. This arises during the period of adaptation to significant events beyond an individual’s control. Such an experience uproots a life and introduces great levels of stress.

While diagnosing Sherman’s malady more than a hundred and fifty years after the fact is problematic, Reid’s perceptive suggestion is serious food for thought. Since adjustment disorder is temporary and patients often have rapid recoveries, there does seem to be a convincing case to be made. Like Lincoln, Sherman would exhibit melancholia in episodes throughout this life, but the Kentucky affair never recurred. Time, success, and confidence seemed to be the cure.

The Battle of Shiloh and Vicksburg Campaign have been seen by historians as redeeming, confidence-building experiences for Sherman. They also led the Ohio general to new conclusions about warfare and the necessary means to succeed. “We must make this War so fatal and horrible that a Century will pass before new demagogues and traitors will dare to resort to violence and war, to achieve their ends,” Sherman wrote. But as Reid observes, “the means he sought to create such conditions were altogether more subtle, based increasingly on the demonstration of superior military force rather than on its naked and brutal application.”

Sherman’s rise during the war was nothing less than meteoric. He ascended from division command in the Spring of 1862 to army group commander – directing the movements of three armies – during the Atlanta Campaign which culminated in the capture of Atlanta in September 1864. His success, moreover, had real political ramifications helping to secure the reelection of Lincoln who had appeared to be on the ropes. “Sherman did more than any other man,” Reid concluded, “in creating this climate of opinion. His ingenuity, pertinacity, and prudent calculation were vital elements in his triumph. Strategically, operationally, and logistically his handling of the Atlanta campaign was superb.”

Sherman’s March to the Sea and Carolinas campaign has been recalled variously as dastardly or brilliant and has done much to affect his reputation. The burning of Columbia, South Carolina, is often pointed to as evidence of the general’s barbarism. “The “burning” is represented as the appalling climax of “Yankee barbarism,” Reid suggests, “with Sherman as its devilish anti-Christ, complementing the Christlike Robert E. Lee, suffering as his cause collapsed.”

Of the many controversies surrounding Sherman’s actions in 1864 and 1865, the terms of surrender he offered Johnston at Bennett Farm, North Carolina, rates high among the most debated. While Sherman thought the terms he offered, which encompassed both military and civil affairs, were in line with what Lincoln had wanted, they instead caused a firestorm in Washington. Secretary of War Stanton even intimated that the fiery red head was a traitor. Sherman, of course, was furious that his integrity was being questioned. “However, aggrieved he may have felt,” Reid wrote, “only one author of his troubles could step forward – himself.” Clearly, Reid believes that Sherman had screwed up. “Sherman had proved an impulsive and opinionated man with great faith in his own judgement – but on this occasion he had assumed too much.”

In the final chapter of his masterful tome, entitled “Weighed in the balance and not found wanting,” Reid provides a lengthy evaluation of Sherman. He concludes that “this man of achievement was in many ways a sympathetic character, likeable and much liked, who enjoyed extraordinary restless energy, but he could be choleric, impulsive and vindictive if crossed…Sherman’s importance is indisputable, as icon, hate figure, or moral scapegoat.” While it is clear that Reid admires his subject, his book is no hero-worship; it is a warts-and-all treatment of the man and the warrior. It is essential reading that may well be the best definitive biography of Sherman to date.

thanks Derek … great review.