Purge of the Second Louisiana Native Guards

Sometimes courage and leadership among military officers lies not in leading a battlefield charge, but challenging injustice directly. Such leadership occurred by the line officers of the Louisiana Native Guards, the largest concentration of African American military officers in the Civil War, who encountered trials on the battlefields and in camp while facing a determined and thorough purge of their ranks by senior commanders who did not trust them with the responsibility of command.

The Louisiana Native Guards often gets attention because of its origins. In 1861, many wealthy and elite freedmen of New Orleans organized an African American militia. Provided uniforms, but not entrusted with weapons, the Native Guards famously marched in Confederate parades through the crescent city’s streets. When David Farragut’s naval squadron ascended the Mississippi River however, the Native Guards were left behind in the Confederate evacuation.[i]

Major General Benjamin Butler, desperate for reinforcements to expand control of southeast Louisiana, renewed the idea, organizing three regiments of Native Guards in late 1862. They spent that year’s latter months garrisoning areas between New Orleans and Brashear City (modern day Morgan City) on the Atchafalaya River. What made Buter’s Louisiana Native Guards unique was its officer corps. While the senior field officers were white, the regiments organized with African American and mixed-race and creole company line officers.

As 1863 dawned, the First and Third Native Guards remained in Louisiana, guarding the approaches to New Orleans and the rail lines connecting it to Brashear City, while Colonel Nathaniel W. Daniels’ Second Louisiana Native Guards was reassigned to guard the Louisiana and Mississippi coastline. Seven companies of the Second landed at Ship Island in January 1863. There Daniels found a “good Headquarters,” but “no barracks for my soldiers.” The men immediately began adding to the island’s fortifications and constructing shelters. Within a month, they had enlarged its defenses to include “rifle pits, barricades, and two large magazines.”[ii] The regiment’s remaining three companies went to Fort Pike, guarding Lake Pontchartrain and Lake Borgne.

Racial tensions quickly heated at Ship Island. Elements of the Thirteenth Maine and Eight Vermont Infantry Regiments were also at the barrier island. These white soldiers resented working alongside the Native Guards and a number were arrested for insubordination against the Second’s African American and creole officers. Tensions escalated so quickly that the white soldiers were transferred off Ship Island in February 1863.[iii]

The insubordination convinced Major General Nathaniel Banks, who replaced Butler at the end of 1862, that the African American officers had to go. Banks commenced a systemic purge of these officers by convening competency boards to evaluate the fitness of all African American officers. Captain Samuel W. Ringgold highlighted the discriminatory issues of these boards in a letter to Banks, protesting that “a Board of Examination has been formed to investigate the Military Capacity of the Colored Officers of this Regiment and that the officers detailed to compose said board are in the majority of inferior rank … whose promotion would be effected by our dismissal.”[iv]

The purge began when three officers of the Second failed their competency boards in February 1863 and were relieved for incompetence. In response, the remining African American officers, both those at Ship Island and Fort Pike, sent a letter to General Banks protesting the competency boards. “From the many rumors that have reached us,” the officers noted, “we are led to believe that it is the intention of the General to relieve us.”[v]

(Nathan W. Daniels Diary; Vol. I, mss84934, Library of Congress)

One by one, the regiment’s African American officers faced the competency boards. Those who passed the examination faced continuous prejudiced treatment to the point that many began resigning their commissions in protest. Captain Arnold Bertonneau initially volunteered hoping that “the success of my country would suffice to alter a prejudice which had long existed.” Instead, after surviving his own competency board, he resigned his commission in March 1863, after his “five months experiences proved the contrary”[vi] Captain Samuel W. Ringgold, who complained to Banks of the contradictions among the examination boards, resigned in July 1863 as a protest after passing his own examination. Joining him in resigning that month was Major Francis E. Dumas, a wealthy creole officer who, after inheriting numerous enslaved persons just before the war, freed them to allow them to enlist with the Native Guards as well.[vii]

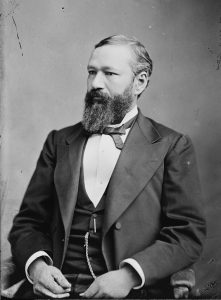

(Library of Congress, LCCN 2017893136)

One of the last African American officers of the Second Louisiana Native Guards was arguably its most famous member, Captain P.B.S. Pinchback. Serving as the “only Colored officer” at Fort Pike, Pinchback tendered his resignation in September 1863, noting the regiments white officers constantly acted “inimical” and would produce nothing “but dissatisfaction and discontent.”[viii] Nine years later while serving as Louisiana’s lieutenant governor, Pinchback took the oath of office as the state’s – and nation’s – first African American state governor, when he stepped in after Governor Henry C. Warmoth was impeached in 1872.

Only one African American officer, First Lieutenant Charles S. Sauvinet, retained his commission to the war’s conclusion within the Second Louisiana Native Guards – reclassified in the summer of 1863 as the Second Regiment Corps D’Afrique and in 1864 as the Seventy Fourth United States Colored Infantry. The other two regiments of Native Guards underwent a similar purge of African American officers, even as they participated in the siege of Port Hudson. Their fighting spirit undeterred, at least ten of these resigned or dismissed officers sought to recruit more regiments where they might regain their commissions and prove themselves in battle, but Banks refused.[ix]

The Second Louisiana Native Guards spent the rest of the war guarding coastal Louisiana and Mississippi. Because of this, it largely became a footnote in the Civil War’s landscape, especially compared to its brother regiments who fought at Port Hudson. Though it did not participate in any major battles, the regiment served as a proving ground for African American soldiers and officers. These officers however, faced Nathaniel Banks’ competency boards, highlighting the many challenges African American soldiers encountered elsewhere, including discrimination and lower pay, throughout the war and the follow-on reconstruction process. Ultimately, their resistance to this purge through resignation and protest highlighted the spirit of the African American community to fight for equality while contributing to United States victory in the Civil War, as well as the desire to shape the postwar nation.

Sources:

[i] “The Parade This Morning”, The Daily Picayune, New Orleans, LA, November 23, 1861; “The Louisiana Native Guards”, Daily Crescent, New Orleans, LA, December 9, 1861.

[ii] January 12, January 21, and February 16, 1863, Nathan W. Daniels Diary; Volume I, 1861, Dec.-1864, May, mss84934, Box 1, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

[iii] Theresa Arnold-Scriber and Terry G. Scriber, Ship Island, Mississippi: Rosters and History of the Civil War Prison, (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2008), 55-56; Edward T. Cotham Jr., Ed., The Southern Journey of a Civil War Marine: The Illustrated Note-Book of Henry O. Gusley, (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2006), 134.

[iv] S.W. Ringgold to Nathaniel Banks, July 7, 1863, Ringgold, Samuel W., Compiled Military Service Records of Volunteer Union Soldiers Who Served the United States Colored Troops: 56th-138th USCT Infantry, 1864-1866 (hereafter CMSR), 300398, RG 94, National Archives, Washington, DC; Edwin C. Bearss, Gulf Islands: Ship Island, Historic Resource Study, (United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Denver Service Center, July 1984), 215.

[v] PBS Pinchback to Nathaniel Banks, March 2, 1863, Ira Berlin, Joseph P. Reidy, and Leslie S. Rowland, ed., Freedom: A Documentary History of Emancipation, 1861-1867, (Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, 1982), Series 2, 321-323; James G. Hollandsworth Jr., The Louisiana Native Guards: The Black Military Experience During the Civil War, (Baton Rouge, LA: LSU Press, 1995), 73.

[vi] Arnold Bertonneau to Wickham Hoffman, March 2, 1863, Bertonneau Arnold, CMSR.

[vii] Francis Dumas to A.G. Hall, July 31, 1863, Dumas, Francis E, CMSR.

[viii] Eliot Bridgman to G. Norman Luibes, September 9, 1863, and P.B. Pinchback to N.P. Banks, September 10, 1863, Pinchback, Pinckney, CMSR.

[ix] Charles S. Sauvinet Service Record, CMSR; Adolph J. Gla et al. to N. P. Banks, 7 Apr. 1863, Letters Received, series l920, Civil Affairs, Department of the Gulf, U.S. Army Continental Commands, Record Group 393 Pt. 1, National Archives.

Great article! I finished reading a book about Benjamin Butler, but it only detailed how he had reinstated the Native Guard, not its latter history under Banks. Thanks for sharing your research!

It truly was a civil war.

If we could go back in time, a conversation with Francis Dumas would be in order. André Cailloux’s history with the 1st La Native Guards has always interested me. As you know he was one of the men who turned out for the free black militia in New Orleans in service to New Orleans’ Confederates, and then after New Orleans fell to Farragut enthusiastically joined the Union cause. KIA at Port Hudson and then had about as big, if not bigger public funeral, than Lt. Col. Charles Dreux had (the former city or district attorney in New Orleans) in 1861 after he was killed on the Peninsula in Virginia.